Work, Fight, or Forfeit - Part 3 of 3

Wherein Americans fight a lot, but eventually work together to do great things. Huh.

It’s time for the final chapter of our latest forfeit story! We love looking at history through the prism of baseball here at Project 3.18, and we found a lot to look at in this tale.

If you have been holding off until the end, here are links to the earlier installments.

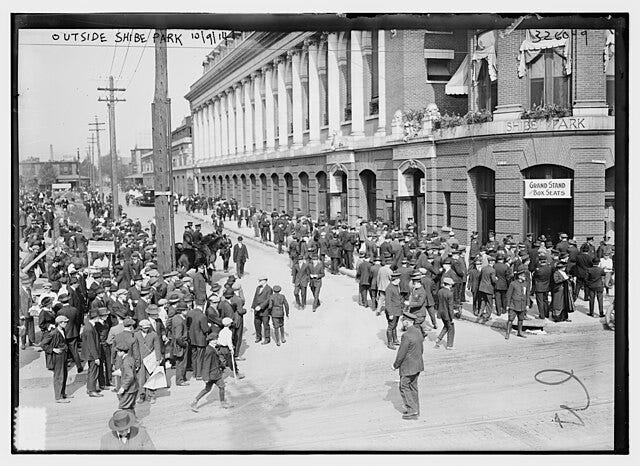

On July 20, 1918, the fans came to Philadelphia’s Shibe Park to enjoy what had suddenly become the twilight of a baseball season dimmed by war in Europe and heartless government officials at home. The large crowd of 14,000 was boosted by nearly 2,000 sailors and soldiers who, the Philadelphia Inquirer darkly observed, “will now have to seek other amusements.”

In the first game, the A’s “viciously assaulted'' two Cleveland pitchers with a Deadball-style barrage of scrappy hits, including five successful bunts and four steals. Philadelphia won, 10-4, in just under two hours.

The teams exchanged roles for the second game, which the A’s “made a very thorough and complete job of losing,” according to the Inquirer.

Blame for the loss fell on “a flock of fuzzy pitching” by a young A’s pitcher named Leslie Pearson, who walked five men, hit another, and got thumped “for four loud and lusty blows” in the first two innings, leaving the home team down 6-0. Poor Pearson did not survive the end of the second.

The A’s, on the other hand, could do nothing against the Cleveland pitcher, Johnny Enzmann, who gave up just four scattered hits all afternoon and one unearned run in the second. With only a handful of A’s reaching base all day, there seemed little hope of a thrilling turnaround. By the bottom of the ninth, the home team was down, 9-1.

By then, the spectators “were wearied by the two long and one-sided contests,” the Cleveland Plain Dealer wrote, but the truth is that baseball fans in 1918 had wearies thrown at them from all directions.

The ballgame: quickly lost at the abrupt end of what had become a lost season. Goods: rationed, expensive, and hard to get. Jobs: called into question by the government. Friends and loved ones: training and fighting in someone else’s endless war. And who knows if there were even any restaurants and saloons open nearby to escape to, thanks to Provost Marshal General Crowder, who had marched off all the male waiters and bussers several weeks prior. Fun was under attack by enemies foreign and domestic.

Unconsciously needing to fight back, the people in that crowd turned to each other. Well, actually, they turned on each other.

There is no record of exactly how it started, but during the bottom of the ninth, some crew of miscreants out in the “fifty cent” stands picked up their heavy seat cushions and threw them into the crowd in front of them. Those coming under unexpected bombardment surged forward to get out of the way, and many gathered up the reusable missiles and returned fire. The flurries of hassocks spread and multiplied, drawing closer and closer to the front row seats and then, inevitably, past the foul lines and onto the playing field itself.

When the cushions started falling onto the diamond, the game was halted in an effort to restore order and regain the crowd’s attention. This, of course, did not work, because how could any group of 2,000 people collectively and simultaneously agree to stop an in-progress pillow fight?

Security might have helped, but according to the Plain Dealer, throwing some turn-of-the-century shade, “the park was not policed except for a half-dozen survivors of the War of 1812, and they could have no more stopped the fun than they could have dammed Niagara.”

The paper also reported that no city police were present to lend a hand and stop the flow of fans tumbling out onto the field, seeking relief from the cushion barrage or to replenish their ammunition from what was available on the grass.

As it always is with children playing rough, things inevitably got out of hand, with some men opting to dispense with the cushions. A large fistfight broke out near first base, where “a red-headed unknown emerged decidedly the worse for wear.”

When the first trespassers weren’t arrested or even bothered, more people climbed out of the stands, sensing a new and novel diversion. Soon their numbers made the situation hopeless. Connie Mack, the A’s manager and part-owner, had a conversation with the two umpires present, Dick Nallin and Bill Dineen. Fearing injuries and without anything to play for, Mack told the umpires the A’s could not fulfill their obligation to clear the field and requested the umpires put everyone out of their mercy. Nallin forfeited the game to the Indians.

The stakes in that decision were low. It was custom at the time for a forfeit to overwrite whatever had taken place in the game with a 9-0 score, which in this case deprived the A’s of just their final three outs and their solitary run.

The forfeit ended the day’s baseball, but with no one to clear them, “several hundred” of the on-field congregation remained for a half-hour after the players had gone. “There were several private fist fights with considerable blood shed,” prompting the Inquirer to observe that many of the fans seemed to have misunderstood the intent of the “work or fight” order now descending on baseball.

“The battle that interrupted the ball game continued,” the Inquirer wrote, “until it fought itself out and disappeared in a thin line of fighters who were last seen chasing themselves out the right field exit.”

The Washington Times-Herald summed up the afternoon’s cracked and punchy nihilism:

[The] stage cops tried their best to shove the fans off the field, but they failed. Cushions filled the air and one or two cops were upset and lost their helmets. Here and there a brawny fan took a punch at a cop only to get one in return.

The Shibe Park fans had made their own fun, and “a merry time was had by one and all.”

This was the only forfeit of that season and the fifth and last of the decade, compared to a total of 22 in the 20th century’s first ten years. The game on the field was growing up and becoming more orderly, but what was happening off the field in the summer of 1918 had become an existential mess.

Before his team creatively split the day’s games with Cleveland, Connie Mack gave his thoughts on the work-or-fight situation:

It certainly looks very bad for us. We have just lost another player…who has joined the navy. If all our players are taken from us I do not see how we can continue.

I had hoped that the big leagues would be allowed to finish the season before the players were ordered to go to work. We have less than three months to go, and we have already lost a large percentage of our best players who have enlisted, been drafted, or gone to work... If we are given a month’s time to reconstruct our teams I think we might be able to finish the season.

Meanwhile, the leagues could not get on one page. As the fans in Philadelphia sent the shortened season off with burlap fireworks, the men in charge released very different statements about baseball’s next move.

The National League president, John Tener, seemed inclined to try and stall, but Ban Johnson was already turning off the lights in the American League, saying no further appeal would be made and that there would be no effort to finish the season with replacement players. The games of July 21 would be the last. Johnson seemed positively (and rather ominously) eager to get on with it:

Evils have crept into the game. Wasteful extravagance on one hand and lack of proper government on the other have been overlooked in the hurry and bustle of the times. I think the national emergency ultimately will be of good to organized baseball in giving it a much-needed opportunity to clean house in its business methods…and in the membership of some of its present family.

Told what Johnson had said, Clark Griffith, manager of the Nationals, declared that the AL president was “talking through his hat.” In a last-ditch effort, Griffith went to see General Enoch Crowder in person, where he pled for one more chance, asking if Crowder would sit down with the game’s leaders and hear what his order was about to do to baseball.

The Provost Marshal General had no particular vendetta against the game (as we have seen, his personal ax was reserved for use against the spiritualists), and he agreed to a special hearing with the National Commission, the sport’s governing body, composed of the two league presidents and an owner representative/president, August Herrmann, of the Cincinnati Reds.

“That the plight of Organized Baseball depended on [Griffith], a team manager, to put in a belated plea for it, after its inaction caused a blow that practically put the sport out of commission, was pitiable to say the least,” The Sporting News wrote.

The situation brings us to this: Baseball, as we see it, will have to be reorganized along new lines…the war is going to be a purifier and a bouncer of shams.

There were certainly shams aplenty among the ballplayers, whose vocational ship had gone from leaking to sinking, prompting many to head for the lifeboats.

It was a time, one writer kindly said, “of haphazard outcomes.” Some draft boards proved friendly, allowing players to continue working in baseball. These lucky fellows, including Joe Finneran of the New York Yankees, seemed to hail from baseball-crazy New York. Finneran’s board even agreed that playing baseball was the only thing he could do well enough to support his dependents, an argument that everyone involved in the Eddie Ainsmith “test case” (right up to Baker himself) had rejected.

On the other end of the spectrum, one Boston draft board ordered every player on the Braves to present themselves and show why they should not lose their draft exemptions. The team was able to clarify that work-or-fight appeals should go to the board overseeing a persons’ place of residence, not their place of work, forcing the crusaders in Boston to stand down.

Some of the more established players had already made enough money in baseball to diversify into other businesses which could now keep them out of the war. On the Nationals, several players, including star pitcher Walter Johnson, would fall back to their working farms. Others on the club had a trucking business and a saw mill, though one with a saloon was reported to be uncertain about his fate. But that still left eight or so other players who had to figure something out. Lucky for them, there was no shortage of offers.

The New York Times reported that since Baker’s ruling, nearly every player in both of the major leagues had considered “jumping” to one of the shipyards or steel plants as soon as possible. Many had gone through with it, resulting in “constant turmoil in the ranks.”

An unofficial and entirely unprecedented “free-agency” had begun, with players trying to secure the cushiest playing gigs (with the least actual labor required) and military-industrial companies competing for the prestige of building the best teams with the most big leaguers.

One ambitious regional outfit, the Duluth-Mesaba League, in Duluth, Minnesota, sent telegrams to many of the game’s best players, including Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Home Run Baker, and George Sisler, boasting of its proximity to many steel plants and shipyards and inviting the stars to jump to their league while working on a nearby government job. Rogers Hornsby was already reported to be under contract.

As he went 6-for-8 during the July 20 games with the A’s, the Indians’ star center fielder, Tris Speaker, was weighing offers. “One of the big steel mills in the east yesterday wired Speaker, asking him to send on the terms of himself and other teammates,” the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported. Signed players quickly became organizers for their new clubs. The same article noted that Speaker’s teammate, Smoky Joe Wood, was already trying to get a group of Indians to join the Bethlehem Steel Company and compete in the Steel League.

The big-league owners, who had gotten quite good at crushing upstart competition, were furious. These industrial leagues were little more than government-subsidized “outlaw” clubs, following the text of the work-or-fight rules, but not their intent. Surely Enoch Crowder had not ordered this.

For his part, Secretary Baker was already looking for a way out, and seemed to like the angle that baseball had thus far received ineffective counsel from its leaders. He issued a statement to this effect to set a tone for the meeting:

I stated in my ruling that the number of men affected by the regulations would not disorganize the industry [of baseball]. Now I am informed that the ruling will virtually ruin the business. These and other facts which were not submitted to me before are to be given to General Crowder tomorrow.

In the July 23 meeting, baseball’s National Commission of Johnson, Tener, and Herrmann submitted every fact they could think of, written in a briefing that contained the economic particulars of the game and a clear explanation of who played it (and how old they were). They asked Crowder for more time, either to the end of the season, scheduled for October 15, or at least enough to wind things up in an orderly fashion, given how much was still unknown about the fates of individual players.

Finally doing something right, the Commission argued that Baker’s rulings had unwisely left player decisions up to 300 different uncoordinated draft boards, making planning difficult, to say the least. Hearing this, Crowder raised an eyebrow. Any impediment to planning was an enemy to the Provost Marshal General, and his icy glare seemed to thaw a little. Might that be sympathy?

Three days later, on July 26, Secretary Baker granted the major leagues a reprieve. The work-or-fight regulations would not apply to their players until September 1.

In a memo to Crowder announcing the decision, Baker praised baseball as “wholesome recreation” and declared it would be “an unfortunate thing to have it destroyed, if it can be continued by the use of persons not available for essential war service.”

It wasn’t a green light, but it wasn’t red, either. Yellow would have to do, and baseball was lucky to get it.

The National Commission had also used their time with Crowder to alert him to the “sham” work some players were doing in the so-called “paint-and-putty” industrial leagues. The thought of ballplayers hiding from war under the skirts of industry did not sit well with the man who’d written the rules. Crowder promised he’d look into it.

Sure enough, on July 30, The Sporting News reported on two players whose industry jobs were deemed too loosey-goosey by the Army’s most uptight man. Tom Daly of the Chicago Cubs and Doug Baird of the St. Louis Cardinals were notified that their work deferments had been canceled and that they were being called up into service. After that, players increasingly opted to stay put and wait until the end of the season before making any other arrangements, pleasing the owners and satisfying General Crowder.

Meanwhile, the interleague squabbling continued. John Tener said he didn’t favor holding a World’s Series at all, but failed to consult the National League owners before taking this position. Ban Johnson favored ending even sooner than allowed (more time to fight evils), on August 20, leaving room for a World’s Series before the deadline.

Herrmann, the Commission’s swing-vote, opted to play through September 2, Labor Day, and then ask for permission (or forgiveness, perhaps) to stage a short World’s Series, which the War Department granted. The Cubs and Boston Red Sox staged a turbulent barely-Fall Classic and Boston won, 4 games to 2. It wasn’t pretty, but it’s there in the record books, and that was a victory for baseball in 1918.

But what about 1919?

For all their shortcomings in sports trivia, Baker, Crowder, and many of their military colleagues had entirely succeeded in quickly preparing the nation for war, and in the summer of 1918, the success of the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe would secure baseball’s future (and, as a bonus, the future of democratic Europe).

In late July, Ban Johnson’s flailing and Clark Griffith’s heroics sat alongside headlines bursting with war news from Europe. And unlike the troubles in baseball, many of the war dispatches seemed upbeat, particularly those from a place in northeastern France called Soissons.

At Soissons, the Entente powers (America’s allies) were on the attack, bolstered by some of the first operational units from the United States, including the Army’s 1st and 2nd Divisions. The thousands of Americans involved were a small portion of the total force, but they were nonetheless the largest body of troops the nation had assembled for one battle since the Civil War.

“The conduct of the men, many who were ‘going over the top’ for the first time, has elicited the commendation of the French,” the Associated Press reported, “who say that the Americans have played their part with steadiness, courage, and skill.”

During the spring of 1918, the German army had thrown the last, best punch it could, a blow the French and British had absorbed, at great cost, while American reinforcements were properly trained. Now, at Soissons and elsewhere, the AEF were at last in the fight, the allies hit back, and the battle proved to be a turning point. The Germans would never again take the offensive. In their first days of real combat, the Americans contributed to what became a pivotal victory.

By October, the Central Powers began to collapse, and on November 11, 1918, Germany signed an Armistice agreement that was largely dictated by its foes. A war many had feared had years to go ended just months after the work or fight order went into effect.

Eighteen days after the Armistice, Ban Johnson wrote the War Department to check in on the prospects for baseball in 1919, but this time—in an atypically savvy move—he went straight to the most senior baseball fan in the Army, Chief of Staff Peyton March.

General March replied on December 5 , taking evident pleasure in delivering the good news:

Unless there is some change in the situation which now seems impossible, there is no reason known to us why the great national game should not be continued next year as usual. The wholesome effect of a clean and honest game like baseball is very much, and its discontinuance would be a real misfortune.

While it would be a long, long way from “clean and honest” in 1919, baseball had survived war and perceptions of its own irrelevance to emerge as a nearly-essential American institution.

At the end of the year, the Chicago Tribune reflected on the game’s tumultuous wartime journey:

The harm done to the good name of baseball, by the comparative few who sought bullet-proof jobs during the season, was more than offset by the fact that more than 50 percent of the players who were on the rosters of the two major leagues in March were in actual service, either in the army or navy, by October, and a considerable number of athletes in both big leagues were overseas before the armistice was declared.

The return of those players who fought, or were willing to fight, to the ranks of the different teams will do more than anything else to restore professional baseball to favor in the eyes of the public and the government.

Now that’s what we call a forfeit.

The Battle of Soissons ended 94 years ago today. While not the little romp we expected, this story of baseball and America doing great things in overwhelming times nonetheless seems timely.

Okay, now we have to change gears. To make sure that happens, we’re breaking the glass on top of one of our dumbest story ideas, making it one we’re really excited to tell. It’s contemporary, it’s ridiculous, and we’re sure it’s never been told in full before, because who would do it?

On August 29: “For the Birds”

A great read, Paul.

I don’t think blacks were drafted at that time so I’m assuming this had no impact on the Negro League?

Another interesting read. Thank you Paul.