The Seattle Mariners Go Thrifting

After their clubhouse was ransacked in 1981, the team patched together a one-night-only uniform.

In a recent piece on identity and the Seattle Mariners’ oft-star-crossed existence, included a wonderful detail that drew us like moths to flame:

One day in 1981, their clubhouse was burgled and they had to wear a different team’s caps and their opponents’ batting helmets. They won that game:

Mariners not in Mariners caps, all-time: 1.000 winning percentage

Mariners in Mariners caps, all-time: .477 winning percentage

We didn’t know about this! But as we always say, Project 3.18 is a journey of discovery, and with thanks to Sam, today’s journey takes us to the den of thieves that was Arlington Stadium, home of the Texas Rangers between 1972 and 1993.

After the May 30 game ended and the players had finally cleared out, the visiting clubhouse at Arlington Stadium was shut and locked. The room had one door and no windows.

For most of the night, there was a guard on duty. Mike Wallace, who managed the visitors clubhouse at Arlington, had followed his typical practice of sleeping in the clubhouse when a visiting team was in town. Some time between 1 am and 4 am, Wallace left, for reasons unclear, locking the door on his way out.

Gary Nicholson, the Mariners’ trainer, seems to have been first to discover the crime scene. When Nicholson arrived the next day to start preparing for that night’s game, the clubhouse had been pillaged. It did not take him long to sort out what had been taken:

The Mariners’ players hats (all 25 or so)

The players’ jerseys (22)

All the batting helmets (15)

All the catching mitts (5)

Warm-up jackets (2)

Equipment bags (3; empty)

And, last but certainly not least, both pairs of pitcher Ken Clay’s cleats.

The thieves had breached an exterior fence before reaching the clubhouse door, and once inside, they followed a plan, ignoring several expensive pieces of video and stereo equipment in favor of all the memorabilia they could stuff in those empty equipment bags.

Nicholson estimated the total losses at around $3,500 of equipment; items that could fetch twice that amount on the memorabilia black market.

The trainer reported the break-in to Lee Pelekoudas, Seattle’s traveling secretary, and he reported it to the Texas Rangers officials. The Mariners had their pants, and most players had their gloves, but there was not a cap among them.

The jersey situation wasn’t quite so dire. For some reason the thieves had spared the Mariners’ stock of dark blue knit pullovers, which the team usually wore only while warming up or taking batting practice. The practice jerseys had some style—former M’s manager Maury Wills had asked the American League for permission to wear them in a game earlier that season. Permission was denied, but Pelekoudas reported the robbery to the League office and informed them that unless he was to run the most memorable shirts versus skins game in baseball history, the Mariners would be wearing the pullovers at last.

But what about headwear? With the game a few hours away there was no time to receive a fresh batch from Seattle or anywhere else, so Pelekoudas and Nicholson looked to the only source available: the souvenir stands at Arlington Stadium.

The stadium shops did sell Mariner caps, but in a surprising development, they were sold out.

“We took that from a positive approach,” Pelekoudas said. “Gary said, ‘we’ve finally come of age. Somebody wants our uniforms and caps.’”

The two men continued shopping. Texas caps were abundant, naturally, but that wouldn’t do. Too confusing, and besides, according to Pelekoudas, the red of those caps “would have clashed.”

Instead, they cast their eyes around for something closer to blue and gold, until they spotted a goodly supply of Milwaukee Brewers caps. “Those go along pretty well with the tops we’re wearing.”

Eddie Robinson, the Rangers’ general manager, graciously offered to pay for the replacement caps. That was already the least he could have done, but it was slightly worse than that, because these weren’t even game-quality fitted caps—they were plastic mesh, golf-style hats with adjustable snaps in the rear.

As for batting helmets, there was nothing to do but suck it up and share with the Rangers. For a number of Mariners/former Rangers, including 1974 MVP Jeff Burroughs and Lenny Randle, it became a strange little throwback to younger, more proficient days.

“The players didn’t say a whole lot [about the situation],” Pelekoudas said. “But somebody said, ‘with Ranger helmets and Brewer hats (two offensively gifted teams), we should be able to hit.’”

And hit they did, battering Texas starter Fergie Jenkins for nine hits and four runs in five innings, and six more hits against his replacement. The final tally of 15 was their high total for the season to that point, and the “Seattle Strangers” won their only game, 5-3.

The clubhouse raid occurred mid-road-trip, and the Mariners were to start their next series in nearby Kansas City the following day. Pelekoudas placed an emergency call to workers back at the Kingdome in Seattle, and the staff there boxed up every loose hat they could find, a selection of batting helmets, and even, it seems, another pair of cleats for poor Ken Clay1.

Taking no chances, the Mariners brought their Brewers hats with them to Kansas City and warmed up wearing them, but just before game-time the emergency shipment arrived at Kauffman Stadium and, for better or worse, the Mariners were the Mariners again. They managed 10 hits against Paul Splittorff and Dan Quisenberry, but lost, 3-2.

Seattle finished their six-game road-trip 3-3 and gratefully made their way back home to the secure confines of the Kingdome, where they could wear their home whites for the next 10 games while a new supply of road powder blues was hurriedly stitched together in time for their next trip out of town on June 15.

At least, that was the plan.

On June 12, 1981, the Major League Baseball Players’ Association went on strike, locked in a bitter dispute with baseball owners over the still-new institution of free agency. Owners wanted the right to claim a player from any team who signed one of “theirs” as a free agent. The players, led by MLBPA director Marvin Miller, pointed out that such a compensation pick missed the whole point of what it meant for players to be “free” on an open market.

713 games were canceled, almost 40% of the season. The owners mostly caved in by late July, when an agreement was reached to resume the season with the All-Star game on August 9.

The strike cost both sides an estimated $146 million, reducing the Mariners’ loss of $3,500 of equipment in Arlington to the equivalent of a penny falling out of an open wallet—not even worth the effort of bending down.

Perhaps the strike explains why there was no follow-up investigation into the break-in at Arlington Stadium. We would have had lot of questions for Rangers’ visiting clubhouse manager Mike Wallace, particularly given this note in an Associated Press account of the theft (emphasis ours):

This was not the first robbery at the stadium. Last season, the visitors’ facility was robbed when the Minnesota twins were in town.

Folks, we tried to find more details on the aforementioned incident in 1980, but without any luck. We’ll keep at it—we’ve got one heck of a cold case here.

We did find an account of another ill-fated Twins journey to Arlington that year, one that speaks to the ramshackle state of 1981 baseball just as well.

Arlington Stadium began life as a minor-league ballpark, Turnpike Stadium, and like all minor league stadiums it had no overhead protection. This was could be a big problem in the punishing summer heat of the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex area. Once it was bootstrapped into service as a big league ballpark, Arlington immediately became the hottest place in the major leagues, and the Rangers played nearly all their games at night for reasons of health and safety as much as fan convenience.

Near the end of June, 1980, daytime temperatures in the region soared to a record-tying 113 degrees Fahrenheit, just as the Minnesota Twins arrived for one of just two visits they’d make to the park that season.

It was so hot that the bus chartered to take the Twins from the airport to their hotel overheated on the side of the Lyndon B. Johnson expressway, seven miles from the hotel. The Twins piled out of the bus and hitchhiked to their destination in small groups.

As if that wasn’t incredible enough, the team traveling secretary failed to change buses. The broken-down bus was patched up and driven to the hotel, where the Twins piled back in for the 25-mile drive out to Arlington. Three miles from the ballpark, the bus overheated again, this time on Interstate 30. Out came the players, standing on the side of another highway with their thumbs in the air.

“I think we set a record for freebie tickets left at the ballpark,” an unnamed Twin was quoted as saying. “Whenever a driver would pick us up, we’d offer to leave them tickets for their family, neighbors, everybody.”

Carload by carload, they straggled to Arlington, the last group arriving just in time for batting practice. The game-time temperature that night was 109 degrees, and there is a 50% chance that their clubhouse was burgled on this very same trip. It’s a wonder the Twins ever came back.

Postscript: The…Helicopter!?

Required Reading: The Plane!

Writing Project 3.18 is sometimes an exercise in patience. Any time we post a contemporary(ish) story, we do so in the hope that an eyewitness might see it and add on to our written account. This sometimes takes a while, but when it happens, look out.

A year after press time, we were delighted to hear from such an eyewitness. As a young boy, John G found himself in the stands of Dodger Stadium on the very remarkable evening of September 4, 1971, when the ballpark was flour-bombed from the air.

John recently left his memories in a comment on the original story, and boy does he add a wrinkle:

I attended that game with my Dad! I was almost 11 1/2 years old. I remember it well! Sounded like a cannon went off. Lotta confusion, lotta flour dust. I remember everyone had turned up their portable radios so they could hear Vinny (broadcaster Vin Scully) report everything that was going on. First reports were that the LAPD was chasing the suspects with their helicopter and the suspects were also in a helicopter.

I remember hearing nothing until the impact. Whoever they were, they knew what they were doing. They had to have been gliding. I guarantee anybody who says they heard a plane or a helicopter leaving the stadium was full of it. Because there was way too much noise down on the field and in the stadium. We were on the loge level, press box level off of the third base line. I had a perfect view of what happened. There was a lot of speculation. But we were all told that the LAPD was chasing the helicopter. Then we never heard another thing about it.

I thought it was kind of weird because my father was a film editor at [a local network affiliate station] at the time. It's like they never spoke of it. It's almost like they were all told to keep it under their hat. I don't know why but it was kind of weird, very mysterious.

Reports of a helicopter chase through Los Angeles. This story has reached Michael Bay levels of action—plus a rooster.

It’s good to hear John say that the way the event (literally) came and went seemed strange, even to people at the time. Perhaps there was concern that publicity of the flour-bombing would encourage imitators. In the early 1970s its more plausible to think the media may have cooperated by muting their coverage. Good luck with that today.

In closing, John mentioned he’d had a lot of other weird stuff happen to him at Dodger Stadium, and we promised him our inbox doors were open. John, if you see this, thank you and start writing!

And a reminder to all that comments submitted after publication day are seen, appreciated, and may end up featured. Comments including details of an aerial pursuit will receive priority.

Postscript: Three Questions for You

We continue to tweak our process and presentation here at Project 3.18. As we tinker, we’d be so grateful if you (yes, you!), our discerning readers, could give us some feedback on what you like to see in your irreverent, off-kilter, long-form baseball history writing.

We’re going to try using Substack’s poll feature, which should be easy for app readers to use. Email readers, a click should take you where you need to be to answer these three questions—we hope you will!

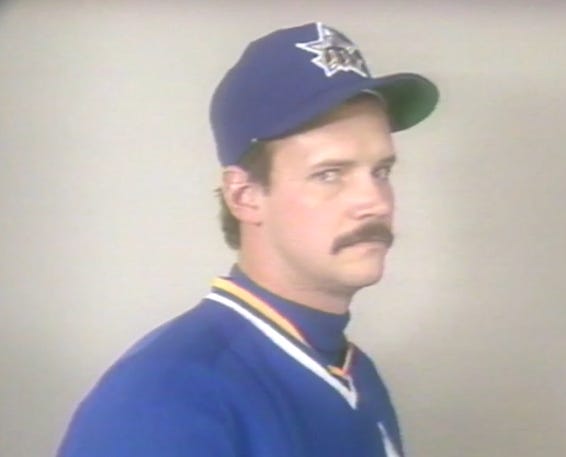

Did you provide feedback? Thank you! Here’s a link to a very cute Mariners commercial from 1981.

If you didn’t provide feedback, Richie Zisk will know…

Relievers didn’t work as frequently back then, but Shoeless Ken Clay did pitch on the last game of the road trip, and we’re assuming the Mariners wouldn’t have made him pitch in sneakers. Then again, he gave up 6 runs, including a grand slam, and failed to record a single out, so who knows?

I would think first of the (single season) Seattle Pilots rather than the Mariners when it comes to quirky stories - Jim Bouton covered many of them in “Ball Four”. But, this visit to Arlington is a strange one - good stuff, Paul.

Great read Paul!