The Old Slow-Ball

On baseball's 1940s barnstorming circuit, an unassuming hero put on a one-man clinic that we're still talking about today.

America couldn’t get enough baseball in 1946. Attendance records shattered coast-to-coast as servicemen and women returning from World War II binged on leisure activities and easing wartime demands on industry led to more days off for essential workers. After some lean years, that postwar summer was one big baseball bounce.

The country went so baseball-mad that the major leagues couldn’t keep up. Every road trip left a baseball-crazy city in need of its next fix. Traveling barnstorming teams filled the void, renting out the big ballparks to stage their own colorful exhibition games.

Barnstorming games were sketchy affairs, contested by mercenary clubs stocked with players not quite good enough to make the pros, former big leaguers past their prime, or those shut out by the segregationist commissioner. Out in these margins, the rules and standards were loose and improvised. Novelty was encouraged and spectacle was a priority.

New York’s Polo Grounds were a perfect venue for these games. The park’s name was silly—no meaningful polo had been played there since 1880. The field dimensions were wacky—279 feet down the lines and 483 feet into deepest center. The park would have been the perfect place for a Roman circus, and on this day in 1946 some faded local heroes were going to be fed to the hyenas.

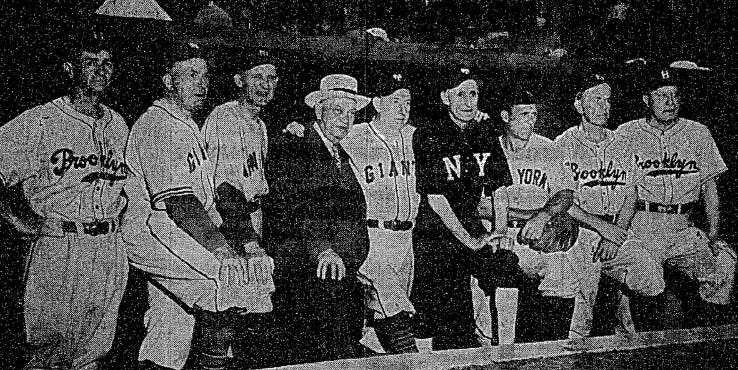

Old-timers were a staple of exhibition baseball. Watching men long past their prime suit up and play again evoked feelings of nostalgia and melancholy, and complex emotions sold tickets. Among the Tea Totallers were men who had once played for John McGraw, dug in against Christy Mathewson, and dared Honus Wagner to hit their best, but here in their latter days they needed spectacles and a few seemed to have forgotten to put in their false teeth. Though their bodies were going, their minds wouldn’t let them leave baseball. They formed a local club and took on all comers in New York’s green cathedrals. Win or lose, their cut of the gate receipts supplemented their meager pension payments.

Some of them were old enough to recall the days when players could call for their pitch—high or low. The greenest among them was not a day less than 70, and eldest, one Billy Gray, claimed to be north of 93 (though his teammates felt Gray inflated his age in a play for sympathy). They donned their red and light-grey uniforms, smelling faintly of mothballs and liniment, and took the field once more, now playing for a crowd whose mothers and fathers couldn’t have remembered their names.

The day’s rented opposition were a pack of free-swinging, power-hitting brutes who worshipped the long ball, sacrificed the umpire, and slid in spikes-high on a base-on-balls. Despite their physical gifts, none of these men had ever reached the big leagues. Too mean to be taught and too dumb to learn, off-speed pitching took them to pieces. Driven out of baseball, they all drifted inevitably into heavy industry, spending their free time playing baseball on company teams, bludgeoning each other for extra commissary scrip and blowing it all on beer and cheap cigars. Their style of play fit right in to this violent world. Once the war ended and the real players had gone, nobody threw a curveball in the shipyard and foundry leagues, but hitters sure did learn how to duck.

They were a military-industrial All-Star team, scraped from wharves, railyards and refineries all along the East Coast, playing semi-pro and local clubs who’d not yet learned of them the hard way. Calling themselves the Gas-House Gorillas, they gambled on their own games and always bet on themselves to win.

Blue and ash-grey uniforms hung off their bulging arms and legs and guts in tatters, having been stripped off the still form of a smaller, weaker man whose position had just become available. Straight razors broke on the stubble of their faces. They smoked cigars made from hollowed baseball bats and their spikes were made from rail crampons. The Gorillas watched the Tea Totallers attempting to limber up in the outfield (two wizened men had to be carried away from their warm-ups on stretchers) and they grinned, showing jagged, tobacco-stained teeth smashed in arguments over the batting order.

Over 55,000 fans filled the Polo Grounds to capacity, the largest crowd ever for an exhibition game. They’d come to see a massacre, and the Gorillas would provide.

The game was so anticipated that the teams had even arranged to have it broadcast over the radio. The Giants’ regular announcer, Russ Hodges, was off when the team traveled, so the game was called by 32-year-old voice actor trying to break into radio. Frank Graham could hardly keep up with the pace of the Gorillas’ attack, and the curtain seemed to have barely risen before the Gashousers were up an unfathomable 40 runs over the doddering local club.

Graham told his listeners he had never seen such a shellacking. He could barely finish a sentence before some Gorilla hit another screamer, sending Totallers and bleacher creatures scattering under the bombardment.

“The home team hasn’t a chance,” Graham said during the middle of the fourth, “but they’re in there punching.”

The Gas-House pitcher only knew how to throw fastballs, but that was enough against men whose fast-twitch muscle fibers labored under age’s three-second delay. Just in case the Totallers started timing the pitcher up, the Gorilla doing the catching would sometimes stand in front of the plate to receive the throw. With their failing eyesight, the Totallers often swung anyway.

The umpire was an amateur, too, less than half the size of some of the men he was supposed to keep in line. Eventually the Gorillas did away with him altogether and gave his mask and chest protector to one of their own. Sportsmanship didn’t live long on the hard-scrabble baseball lots wedged between foundry and factory, and the Gorillas made no distinction between mercy and weakness.

By the fourth inning the Gorillas had batted around and around, strutting to the rhythm of hard contact. The Tea Totallers’ soft-tossing pitcher nearly threw out his back ducking as one ball after another was swatted at his head.

“Listen to that crowd roar,” Graham said. “The Gas-House Gorillas are up to bat again!” Soon it was 96 to nothing, but the teams were under contract to play nine innings, so on the pummeling went.

The mob loved it, cheering each new tally on the board. But in quieter moments, there was one voice of dissent, crying out for fair play and decency in a thick Flatbush accent. The strident fan was seated in a picnic area beyond the left field bleachers. Wearing a straw boater hat and a napkin around his neck, in between bites of his lunch he berated the visitors in his piercing nasal voice, giving the Gorilla outfielders no peace and no mercy.

“Boo! Boo! Boo! Nyah, youse Gas-House Gorillas are a bunch of dirty players!”

Though alone in his section, he seemed to confide in someone:

“Why, I could lick them in a ball game with one hand tied behind my back all by myself.”

Three dirty, slab-like outfielders soon towered over the mouthy fan, who issued a cool greeting through a mouthful of popcorn. Speaking with eloquence learned in unlicensed saloons, the Gashousers invited the fan to join them on the diamond and back up his bragging. They’d even give him a sporting chance and let him use both of his hands.

The fan, noting the size of the Gorillas’ bats and recalling their willingness to use them for non-regulation purposes, realized this was an offer he couldn’t safely refuse. He drew himself up and agreed to play.

The Polo Grounds’ public address announcer introduced the new player. Not quite clear what was happening, various spectators wrote the fan in on their scorecards as a substitution at every position. The confused scoreboard operator did the same.

The fan cut a striking figure in his Tea Totaller uniform. He was oddly proportioned, wire-thin with big feet. He hid large eyes and big teeth under the cap, but no hat was going to hide his stick-out ears. Standing on the pitcher's mound, he confronted a lineup of carbon-copy sluggers with evident no weak spots.

As he set to work, the defense seemed to revive itself.

“Come on!” the catcher cried. “Right down the plate! Right down the ol' alley! This guy's a push-over! Come on now, boy, give it to him!”

The first Gorilla to face him was not easily impressed. He had used bigger opponents than this to clean the soot from underneath his fingernails. He stood in, smiling with such malice that parents in the stands covered their children’s eyes.

The obscene grin vanished as the pitcher began his wind-up. It was a herky-jerky tangle of arms and long, long legs. Just as he seemed sure to tie himself in a knot, the fan unwound and fired home. Seeing the ball in all that mess was like trying to find it in a full clothes dryer going at high speed. The batter was soon dragging his club-like bat back to the bench.

“That's the ol' pepper!” cried the catcher. “That's the ol' pitchin'! That's puttin' it over the plate, boy!” From that point on, the Totallers worked as one.

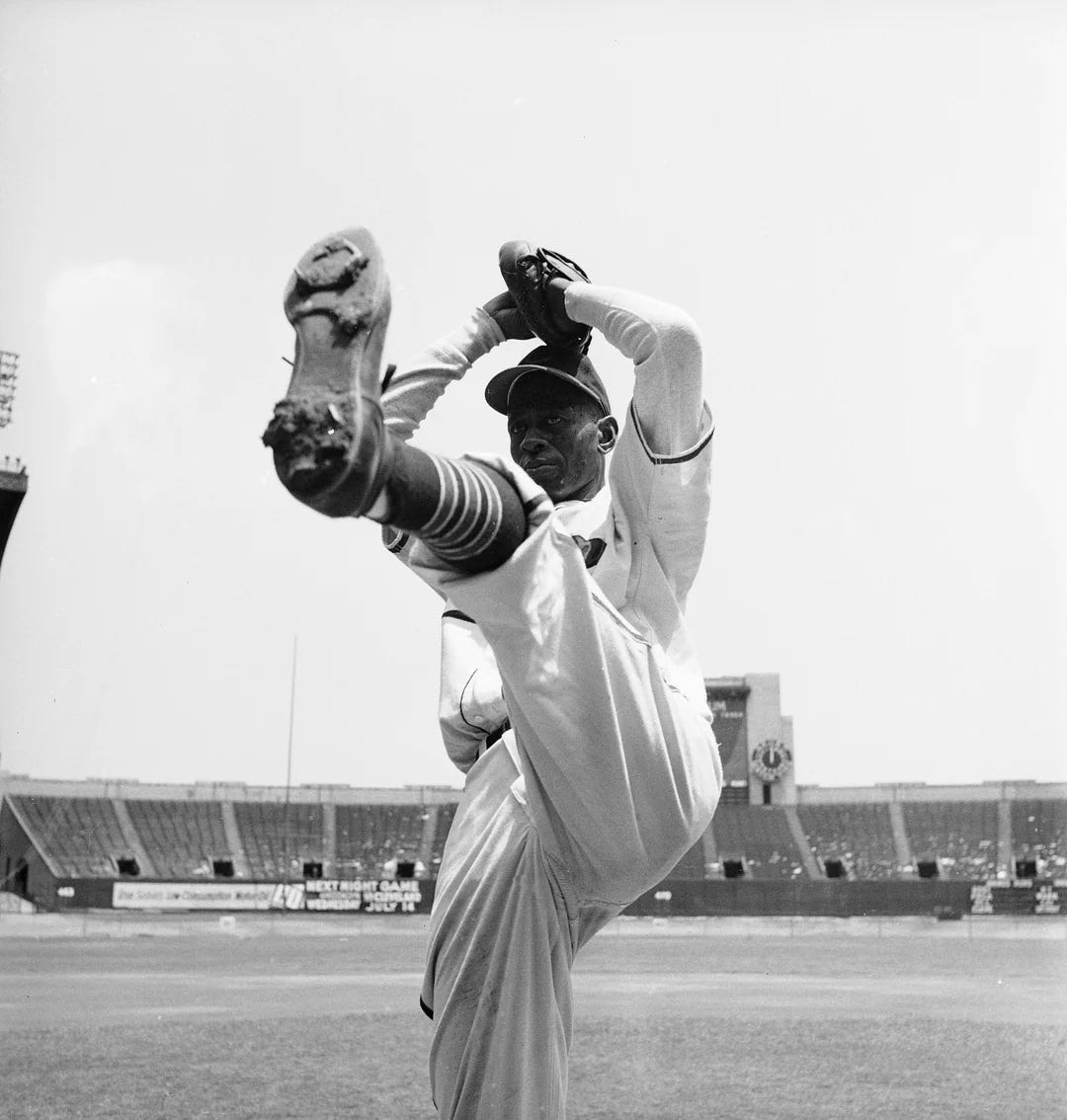

For talent and dramatic flair, some would compare the fan to the great Satchel Paige. The most accomplished Negro League pitcher found another gear when he played in exhibition games, in which he could underline his pitching ability with his showman’s instincts. In one memorable game, he intentionally walked three straight batters and told his infielders to take the rest of the inning off. They sat, and Paige struck out the side.

After striking out the first Gorilla, the fan went after another, with the same results. The bench mob ceased chortling and swilling rye from mugs the size of pony kegs to observe the trouble at the plate and swap worried looks.

One especially capable batter resolved to end the trouble by killing the fan. He crouched over the plate like a trapped predator, furious and afraid. He planned to swat the next pitch right through his opponent’s midsection, and he had the bat control to do it.

The pitcher saw the murder in the batter’s eyes. Turning to the crowd sitting along the third base line, he winked, muttered something that no one heard, then wound up again, a blur of flailing limbs.

More than 55,000 people spun the turnstiles at the Polo Grounds that day in 1946, and a million more New Yorkers would soon claim to have been there, too, all watching from the same seat along the third base line.

The ball inched towards home, barely spinning, an off-speed pitch right out of the Gorillas’ whispered nightmares. It floated towards the batter like a balloon on a gentle breeze, and the murderous batsman flailed at it and missed. He swung again, and the ball danced away. He swung a third time, leaving his own teammate/umpire no choice but to call him out. The same thing happened to the next two hitters. Throwing the slowest pitch anyone had ever seen, the fan used the Gashousers’ all-or-nothing energy to dismantle them. The crowd cheered. They had no favorites, so long as someone left humiliated.

The Gas-House Gorillas still led by 96 runs, but that was the turning point. Brute force had met its equal in the craftiest righthander the game had ever seen.

There’s no clock in baseball, and the fan used that to his advantage on offense. He whittled down the Gorillas’ lead until the last shards fell away and his team went ahead by a single run, 96 to the Gorillas’ 95.

In the booth, a breathless Frank Graham narrated the moment for listeners at home:

“It's the last half of the ninth with the score 96 to 95, the Gas-House Gorillas have one man on base and two outs, a home-run now would win the game for the Gorillas.”

Graham’s play-by-play was critical information—the designated “home team” had changed during the course of the game, and the thoroughly demoralized Gorillas had somehow managed to lose a run.

The last Gas-House batter carried a bat the size of a Mark 14 torpedo. Now on his third time through the batting order, the pitcher knew his opponent had seen too much of the slow-ball. He decided to fight fire with fire. He even told the batter what was coming: a “powerful paralyzing perfect pachydermous percussion pitch.” Satchel Paige threw something similar.

As the pernicious fastball crossed the plate, the Gorilla lashed out. The unstoppable force met an unrelenting object and Isaac Newton took it from there. The ball was on its way out of the park, perhaps out of the borough, but the center fielder refused to give up on it. After all, a baseball caught in home run territory is an out.

The outfielder threw his glove into the air to snare the ball and brought it down, ending the game with a robbery as improbable as it was technically illegal. But this was exhibition play, and the original umpire, so abused by the Gorillas, reappeared to take his own revenge, calling a fair catch.

The defeated Gorillas slunk back to their ironworks, their industrial presses, their rusting scrapyards, discarding caps and gloves as they went. No one who ever played for that club would ever admit being a part of the team that lost that day at the Polo Grounds. Questioners who probed further usually wound up in the hospital.

As for the pitcher who beat them, little beyond this one performance exists for us to remember. He could have walked off the field and signed a contract and starred for any team in the majors. Instead, he drifted off, working various odd jobs. At one point he was said to have dabbled in opera. Bird dog scouts spent years trying to hunt him down, but nobody ever did. He had simply gone to ground.

Next week, we’ll do an opener story, right around the time everybody gets tired of openers. This season we’re going to bring you a few stories featuring some of baseball’s newest Hall of Famers, starting with the arc of Dick Allen’s time with the Chicago White Sox. Allen signed his White Sox contract on April 1, 1972, and his MVP season began two weeks later.

On April 7: “The Good Opener”

Oh, Just One More Thing…

Film records of postwar exhibition contests are understandably rare, but believe it or not, we have actual footage of the game we covered today:

Happy April Fools from Project 3.18!

Note: the above is just the first third of “Baseball Bugs,” but you can find the other two parts pretty easily from there. We wish we could have provided you with one link to the full seven-minute version, but this particular short won’t enter the public domain until about the time Juan Soto finishes out his new contract.

“powerful paralyzing perfect pachydermous percussion pitch.” - that's a lotta' "p's," Paul. . .

Love the article… especially Bugs! Thank you Paul.

I know there are new MLB rules again but I hope they put home plate back facing the right way again. Thank you Bugs 🥕