The Old Man and the Lion

How many Hall-of-Fame pitchers do you need to cover both sides of a 16-inning game? On one incredible night in 1963, the answer was two.

Project 3.18 is a free weekly publication where a fan-first writer tells strange and surprising stories from baseball history and culture. For a great seat, sign up here:

Arthur C. Clarke famously said that any sufficiently advanced technology “is indistinguishable from magic.” Along similar lines, some of the best history could easily be re-shelved under fantasy. Things that shouldn’t have happened, but somehow did. Things that happened, once, but will never happen again.

In the realm of sports, such a fantasy played out at Candlestick Park on July 2, 1963. That night, 15,921 hardy fans watching the San Francisco Giants play the Milwaukee Braves got to see the baseball equivalent of a Homeric epic.

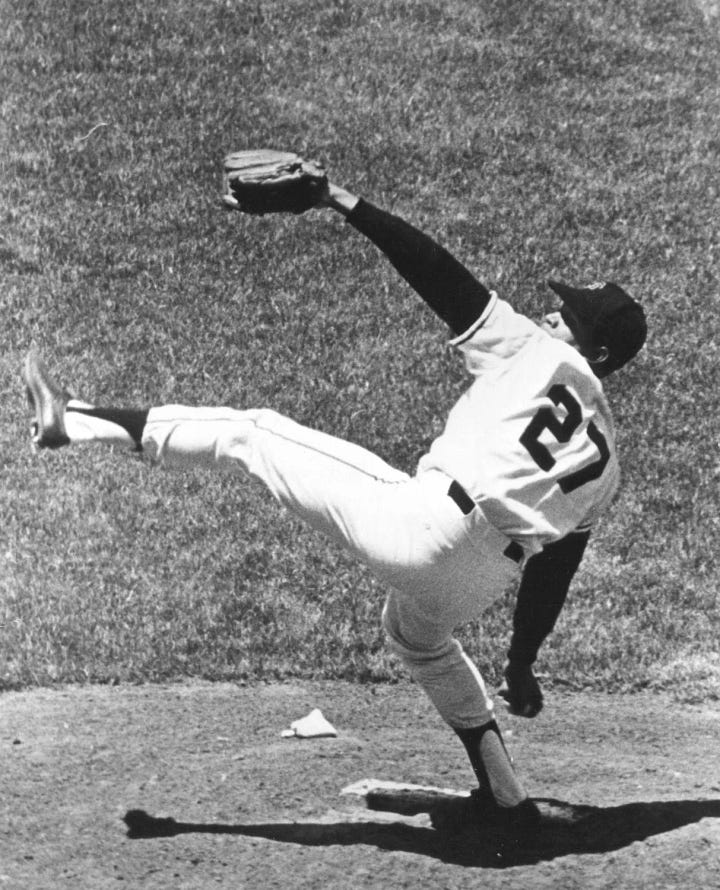

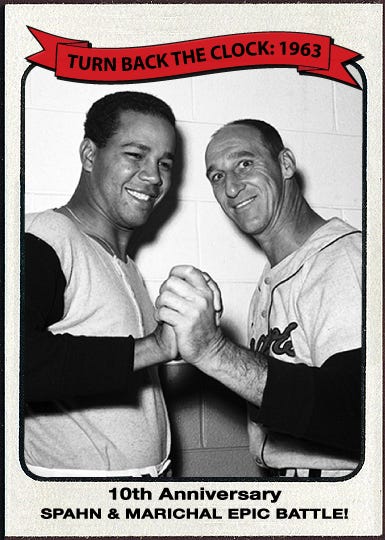

The Braves had a Hall-of-Famer pitching that night. Warren Spahn was 42 years old, in his 18th full season in the major leagues, but still crafting adornments for his inevitable plaque in Cooperstown. If instead of starting he’d retired that day, Spahn would still have finished more games (338), pitched more shutouts (58) and more innings (4,628) than any left-hander in history to that point. A “thinking pitcher” with a high leg kick, excellent control, and a dastardly screwball, he appeared to be immortal.

This story may have a special resonance for us as we approach our 42nd birthday. 42, we now understand, is an age when “standing up wrong” becomes an operating concern; when you start paying much closer attention to where your feet are when running; when unusual physical undertakings echo through the body for days afterward. In our version of 42, most things are harder, some things are much harder, and a few things have already gone out of reach.

This was not Warren Spahn’s experience. Del Crandall, Spahn’s catcher on July 2 (and for 13 seasons) recalled his attitude:

Every year after he got into his 30s, some sportswriter would come up to him in spring training and say, ‘Do you anticipate having the same type of year you did last year?' And Spahn would look at the guy in disbelief and say, ‘Why not? I'm only five months older than I was at the end of last season.'

When his cap covered his thinning hair, it was easy to mistake him for the Spahn of ten years prior. That season, 1953, he won 23 games for the Braves. This season, 1963, he would do so again.

The Giants’ pitcher was youthful vitality personified. Juan Marichal was 25 years old, building on an All-Star season in 1962, his second year in the majors. He was part of a wave of talented Latinos from the Caribbean reshaping a game that—when Spahn started playing—had been almost exclusively White. He too had a high leg kick, and both men threw a diverse arsenal of pitches, but that was where the similarities ended. Spahn threw from the left, Marichal the right. Spahn repeated his delivery and had near-perfect control. Marichal threw every which way and gave up his walks.

No one could seem to get a bead on him. The New Yorker’s Roger Angell once wrote that Marichal “throws like some enormous and dangerous farm instrument.” Some batters said he threw five different pitches; some said ten. The upper half of his delivery seemed almost improvisational. He was as strong as he was dynamic. “It’s great to be young and a Giant,” Larry O’Doyle said in 1907. Across the country and six decades later, it still was.

That July, Marichal was on a tear, even by the pitching-forward standards of the time. He had won eight straight games for the Giants, including throwing a no-hitter on June 15 (requiring only 89 pitches). Spahn was indisputably one of the game’s greatest ever, but just three seasons into his career, Marichal seemed like he might end up somewhere on that list.

Spahn was hot, too. He had a shutout in his prior outing and had won five straight. He had a record of 11-3 going into the game; Marichal was 12-3. As the two aces converged in San Francisco, conventional wisdom promised that someone’s streak of greatness was about to end.

Candlestick Park’s famous zephyrs were in full effect that night, making life difficult for spectators and adventurous for players. It was typically cool, with a wind blowing from left to right field. “The wind helped me against right-handers,” Marichal said, “but you have to be so very careful with the left-handers when the wind is blowing here.”

The Braves’ Hank Aaron was unfortunately one of the former. He provided an early bit of excitement in the fourth inning, hitting what could easily have been his 23rd home run in a season when he’d hit 44. The screaming liner off Marichal ran into a wall of buffeting gusts and died quietly in the glove of the Giants’ left fielder, Willie McCovey.

“I thought that ball was out,” Marichal said. “I don’t think he can hit the ball harder.”

“I thought it was gone, too,” Aaron said. He shrugged. “You can’t beat the elements.” The great slugger went 0-6 that night, but he was in excellent company.

The fourth was what we’ll have to count as an off-inning for Marichal. He struck out the next batter, Eddie Mathews, but a walk and a single put a runner, Norm Larker, on second base. The next Milwaukee batter singled into center field. Larker took his chances, dashing around third to try and score. This was hubris or desperation, because the Giants’ center fielder was Willie Mays. Mays played the ball on one hop and threw Larker out at home like a striking snake.

Offensively, Spahn seemed to have Mays’ number that night. The great hitter went hitless in one at-bat after another, usually putting the ball in play without success.

“These were the kinds of pitchers who kept you on your toes,” Willie McCovey said in 2008. Strikeouts were infrequent and defenders were kept busy chasing grounders and wind-caught flies, as a pleasurable tension built and built. The score was 0-0 in the bottom of the ninth when McCovey led off against Marichal.

McCovey was left-handed, making the Candlestick wind his ally, and surely he had not hit a ball much harder than one he hit off of Spahn in that inning, a towering, game-ending blast that hushed the crowd as it flew straight down the right field line. It was still high above the top of the foul pole as it left the park, landing in a parking lot. Umpire Chris Pelekoudas, a Project 3.18 distinguished alumnus, ruled it foul.

McCovey was furious. He ran to Pelekoudas and argued, backed by a choir of 15,000 people and the Giants’ bench. Manager Alvin Dark joined him, but mostly tried to keep McCovey from chest-bumping his way out of the still-ongoing game.

“[Pelekoudas] didn't make the call right away,” McCovey said later. “I hit it so high and so far, he waited until it landed—which was in Oakland. He was the only person in the ballpark who thought it was foul.”

Triumph picked right out of his pocket, McCovey grounded out. The game went into extras.

Warren Spahn was not coming out. There was no discussion of it. He was a senior statesman, a revered elder who made his own rules, and he pitched as long as he felt. “I'll tell you one thing,” Frank Bolling, the Braves’ second baseman, said, “if you came to take Warren Spahn out of a game, he'd try to shoot you.” The Braves’ manager was Bobby Bragan, another old-ways/best-ways guy who never even came out to check on Spahn. In Bragan’s thinking, as long as a pitcher was effective and wanted to continue, that was his business, quite literally.

Again and again, Spahn walked slowly out to the mound. Innings ticked by. In his first 13 frames, a runner reached third base only once. In the 14th, San Francisco managed to load the bases (Spahn intentionally walked Mays; the only walk he issued that night), but the pitcher escaped. In the 15th, he retired the Giants in order.

In the Giants’ dugout, the situation was more tenuous. Marichal was a great talent, but less of a known commodity—and perhaps a more precious one, given his youth and future potential. This concern is evident in the fact that the Giants were actually counting Marichal’s pitches during the game—no one bothered to do that with Spahn. Manager Alvin Dark certainly didn’t want to be known for breaking a rising star. “I hate to see a pitcher go that long,” he said. In extras, Dark checked in with Marichal after every inning, but the pitcher shooed him away.

“I am not going to come out of the game as long as that old man is still pitching,” Marichal is reported to have said. His catcher, Ed Bailey, was egging him on: “Don’t let [Dark] take you out. Win or lose, this is great.” The pitcher and manager went back and forth:

In the 12th or the 13th, [Dark] wanted to take me out, and I said, ‘Please, please, let me stay.’ Then in the 14th he said, ‘No more for you,’ and I said ‘Do you see that man on the mound?’ I was pointing at Warren. ‘That man is 42 and I’m 25.’

Marichal seemed to be getting better, giving Dark no excuse to pull him. He gave up just two hits across the last nine innings, and kept to his custom of running up to bat and back to the mound (to give himself more time to warm up). At one point he retired 17 straight Braves.

“It was the young lion against the old master,” Willie Mays said in 1993. “I was amazed that Spahnie could keep up with Juan.”

Before the 15th, Marichal thought he spotted a reliever coming in from the bullpen, so he raced out to the mound before Dark could check in.

Each time he walked off the mound, he could briefly glimpse reason: “I said to myself three times, ‘this will be my last inning.’”

But Spahn kept coming out.

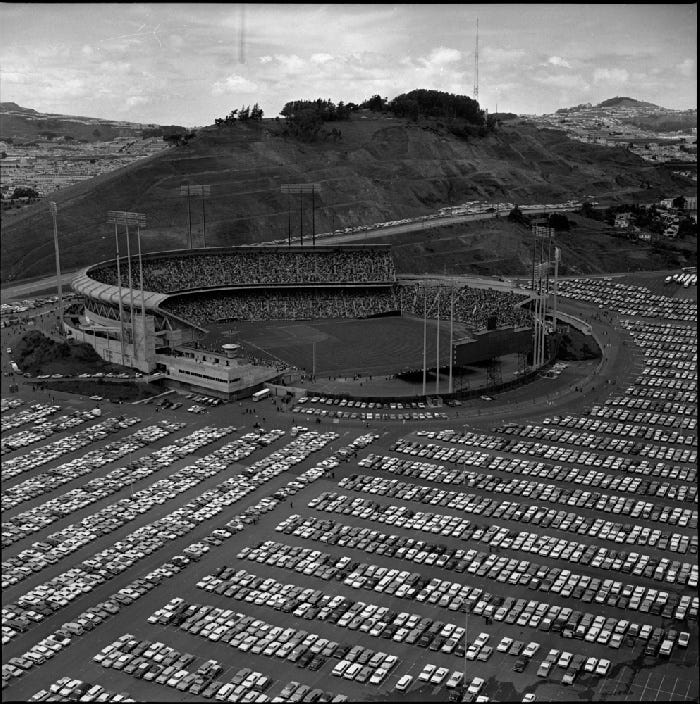

If a game like this was going to happen, Candlestick Park—one of the most hostile environments in the major leagues—was the inevitable setting.

The park was sited between a large outcropping called Bayview Hill and the San Francisco Bay itself. Strong westerly winds would strike the hill and fragment over the playing area and grandstands, playing havoc with the physics of the game and the usual conditions for enjoying it. During the days, the sun kept things mild and the winds weren’t as strong, but after 1pm, things got interesting.

In 1961, during the All-Star Game, Giants reliever Stu Miller was called for a wind-assisted balk, something he struggled to live down. “I wasn’t blown off, I just swayed a little. I don’t know how many times I’ve explained that, but I still meet people who insist they saw me flying through the air.”

In 1963, the wind picked up the entire batting cage and deposited it 60 feet away during the visiting Mets’ batting practice.

Catchers often chased pop fouls that would have reached the seats in every other park, suspicious that Candlestick might make them wind-aided balls-in-play. In 1982, a catcher not familiar with this sort of treachery gave up on such a ball. As he walked back to his station, the wind blew it back out and dropped it on his head.

Vin Scully, the Dodgers’ eminent broadcaster, said Candlestick “had all the warmth of a graveyard.” In the early years, players would stuff their uniforms with newspaper to insulate them. Outfielders occasionally asked for the game to be stopped on account of fog so thick it was impossible to see the ball just a few hundred feet away.

“You had to learn to hit and field with your eyes watering,” a former player and manager said of Candlestick. ”You always checked the schedule and prayed for day games.”

The fans had their own struggles with the elements. A meteorological study performed in 1963 found that nobody had bothered to test the evening winds during the selection of the site. The belated study revealed that, during baseball season, spectators endured winds of between 11-25 miles per hour over half the time, a range that went from “papers blowing, peanut shells scattering, and fans wondering who is going to close the door,” all the way to “noticeably unpleasant.”

Twelve percent of the time, watching a night game at Candlestick was like sitting in the middle of a (sub)tropical depression, with winds from 30 to 40 miles an hour. A longtime Dodgers’ executive recalled huddling with his family and watching the American flag rip away from the center field flagpole and fly off into the darkness.

The team eventually began giving fans who attended night games that went to extra innings a medal. In the 1980s and 1990s, such unfortunates could exchange their ticket stub for the “Croix de Candlestick,” a play on a French military medal, the Croix de Guerre.

Nights like July 2, 1963 surely had an impact on baseball’s home run leader for many decades. Willie Mays insisted Candlestick took at least 100 homers away from him. Eyewitnesses agreed.

“Mays would have hit 800 home runs if he hadn’t played here,” his teammate Orlando Cepeda said. “The wind blew so many back, and it was often so cold that it was difficult to grip the bat, let alone swing it.”

One other thing about the wind: the later the hour, the more it tended to die down. As the 16th inning began, it was close to midnight.

Marichal gave up a lone single in his half. “I was throwing a lot of fastballs and changes out there,” he said.

At this point, accounts diverge a little, and you can see the tall-tale-effect at work between contemporary accounts and those from decades after. What seems certainly true is that after his 16th inning of work, Juan Marichal and Willie Mays had a brief exchange.

“When Willie was in the circle waiting to bat, I called, ‘Hit one now.’ Everyone laughed at me,” the pitcher said, immediately after the game. As the years went by the story would have the 0-for-5 Mays respond, “I’ll take care of you,” or words to that effect. But whatever he said, it is clear that Marichal was done.

“I don’t think I could have gone another inning,” he said. “My back was sore and my arm was sore. I was just tired all over.”

So was the crowd, exhausted by the hour and the unabating Gordian knot of tension the two pitchers had created. “It was getting late and people were tired and leaving the park,” Mays remembered. “So, you go for it.”

Warren Spahn returned to the mound without hesitation. The job wasn’t done, after all. He retired the first batter, Harvey Kuenn, on a fly ball to center field.

By this point, some Giants said Spahn was living off of his fastball only, trusting his pitch-location and the harsh conditions to make outs. But Spahn said he’d continued to use his screwball. “I’d just thrown [Harvey Kuenn] several good scroogies for the first out.” With his first pitch to Mays, he tried another one. Except this one “didn’t break worth a damn.”

“I knew it was gone the moment I creamed it,” Mays said afterward. Everyone else would have to wait and see.

The ball rose high into the air over left field. “Oh, it was beautiful,” Marichal said. The abating winds were as tired as the pitchers, and this ball was too much for them. Kuenn touched home plate and the game was over.

Spahn trudged back into the dressing room to find his teammates lined up, waiting for him. They broke into applause and everyone shook his hand. “It happened so suddenly that my first feeling was one of anger and remorse,” Spahn said. “Then I realized that the other guy deserved some credit, too. And I was thankful that I had pitched well and enjoyed a degree of satisfaction knowing I did a good job.”

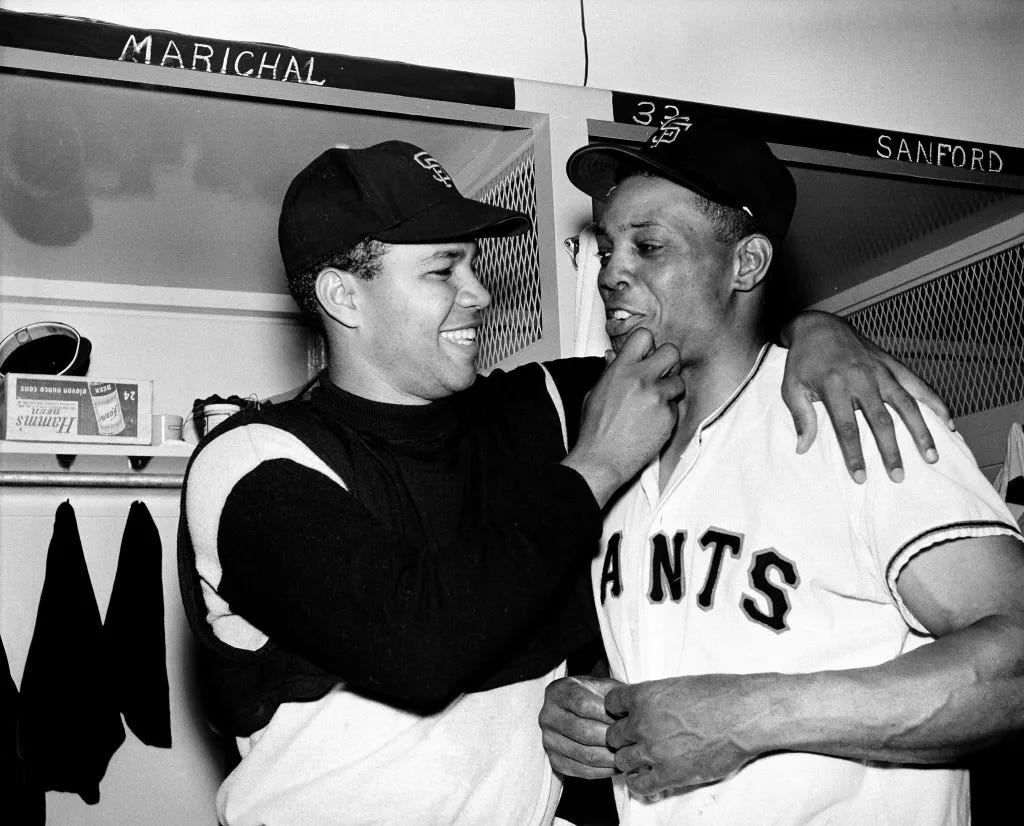

Marichal received a brief rubdown from the team trainer and spent a few minutes in the whirlpool bath before heading home. “Take the day off,” Dark told him, “you’ve earned it.”

It took some time to check the records in those days, but by the next afternoon everyone understood that Spahn and Marichal had fought a duel for the ages. The two came together to take some pictures and compare damage reports. “I feel bad,” Marichal said. “Tired, sore everywhere, arm and muscles.” Spahn said his elbow was barking loudly. He showed Marichal some of the stretches that had evidently served him well through 20 years of repetitive stress. “He told me to take an extra day before my next start,” Marichal said. Can’t be too careful.

The game instantly became one of the best combined pitching performance anyone had seen or even heard of. As time added to the reputation of many of the principals, this midseason affair between two middling teams has taken on a quality of fantasy, a Mad-Lib of a pitchers’ duel, worthy of the Hall of Fame all by itself:

Spahn, Marichal. Aaron, McCovey. Mays.

2 pitchers, 16 innings, 0 runs.

“I’ve been around a long time,” Hank Aaron said that night. “That’s the finest exhibition of throwing I’ve ever seen. It may be 10 years or even 20 years before you see another its equal.”

In fact, it would be forever.

Next week, let’s do a forfeit. We’ll be in the 1940s, which had three. The first was patriotic, downright charming: a horde of scrappy little kids rampaging across the Polo Grounds in 1942 and stealing the occasional pocket watch from a police officer. Now we’ll do the the second, in 1949, but be forewarned—there’s not much cute in this one.

Next: “‘Kill the Umpire’”

Let's not gloss over that Marcial had a 24 pack of Hamm's in his locker, that's awesome! The Milwaukee Braves always found themselves in marathon games, they were the team going up against Harvey Haddix when had a perfect game through 12 innings.

Great article Paul! Would never happen today for a variety of reasons.