The Battle of Atlanta - Part 2

A 1984 contest between rivals deteriorated into a “fiasco” that punctuated a season of brushbacks, drillings, and brawls.

This is Part 2 of our story of an infamous 1984 brawl. Last time, we covered the first eight eventful innings/rounds, so be sure to check that out first.

On April 8, 1984, baseball’s Year of the Plunker began. It started with a near-replay of Tony Conigliaro’s notorious beaning, and another inside fastball that “just took off” and wrecked a promising career.

One of the brightest rising stars at the start of 1984 was the Houston Astros’ shortstop, Dickie Thon, a 25-year-old All-Star who’d been the team’s best player in 1983. He crowded the plate, too.

Thon and the Astros were playing the Mets in Houston on April 8, and he struck out on an outside pitch during his first at-bat. Thon guessed that the Mets’ pitcher, Mike Torrez, would try the same thing when he came up again in the third inning. To counter another outside pitch, Thon edged in even closer than usual, his front foot almost touching the corner of the plate.

But Thon had guessed wrong. Torrez had decided to try mix things up and try to “jam” Thon with an inside fastball. “It was a strategy decision, nothing more,” Torrez said. “But my ball was sailing that day.”

Accounts at the time said the pitch rode up and in, but video footage available today shows a ball that left the pitcher’s hand head-high and arrived at home plate on the same line. Torrez knew immediately he’d missed badly, and he shouted a warning. Thon, looking for something else entirely, lost essential milliseconds to escape. “When I saw where the ball was, it was too late to get out of the way,” he said.

“He ducked,” Torrez said, “but he ducked into it.”

Thon’s helmet rang with the impact, but the man wearing it heard another sound. “It was like a boom. Not loud. It was like a dead sound. Like a thud.” The Astros’ team physician heard it from the box seats near the dugout, and he knew what it was. “I heard a bone break. I guess that’s the doctor in me.”

The crowd fell silent. Thon dropped to the ground, holding his head. He never lost consciousness, and he noticed his vision was blurry. “I didn’t know how bad it was. I was scared. I said, ‘Is this really happening?’”

Thon spent six days in the hospital. There was no brain damage, but the ball had broken the orbital bone around his left eye, resulting in severe swelling and damage to the retina. In his first vision exam after the injury, Thon had gone from 20-20 to 20-150 in that eye.

Ophthalmologists said that Thon’s vision would gradually improve, but the process was slow. In June, standing at the plate, he could see the huge Marlboro Man billboard in the Astrodome’s outfield, but he couldn’t make out the outfielders. Midseason came and went. Attempting batting practice, the ball remained a blur. Al Rosen, the Astros’ general manager, explained Thon’s predicament. A right-handed batter’s left eye was their lead eye at the plate, and the retinal damage had left scarring that obstructed the shortstop’s vision. “It’s like somebody taking wax paper, crumpling it into a ball, then smoothing it out on a table,” Rosen said. “You still have all those cracks in the paper.”

As the Braves and Padres entered the last inning of their August 12 grudge match (short a total of 11 ejected personnel), the 23,900 fans in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium let Graig Nettles have it, booing the Padres’ third baseman as he stepped to the plate to lead off the Padres’ last chance.

Nettles hadn’t played much of a role in the earlier brawl—stars usually stayed out of the worst fights; another unwritten rule. The boos may have come in response to his earlier home run—a misdemeanor offense in every ballpark in America.

Pitching for Atlanta, Donnie Moore insisted that the home run had nothing to do with it. “I didn’t care who was batting,” he said. “I was going to throw at somebody.” And Graig Nettles was definitely somebody.

Joe Torre could have criticized Moore for acting on his own, but the Braves’ manager never did. Instead, he emphasized a larger point: the Padres deserved what they got. “We hit Wiggins,” he said, “whether on purpose or not. They had one shot at Pascual, but they threw at him four times. Retaliation is part of the game but you don’t do it all day and all night.” That breach of norms invited a similarly brazen response, and Donnie Moore provided it with his second pitch, a precisely thrown fastball that drilled Nettles right in the buttocks.

Let’s resume our list, shall we?

Donnie Moore, for intentionally throwing at Nettles

Joe Torre, manager, whose pitcher threw intentionally following a bench warning

Nettles dropped his bat and headed for the mound. He reached Moore before anyone else could arrive, but the reliever executed a last-minute pirouette that gave his infielders the time they needed to arrive.

The Braves’ first baseman was Chris Chambliss, and this was a very good draw for Nettles—the two had played together between 1971 and 1978, first in Cleveland and then New York, where they won two rings with the Yankees. Chambliss brought his old friend down and largely kept him safe as the other Braves tried to take their shots. When the pile came apart a minute later, Chambliss pulled Nettles up and the former Bronx Zoo inmates touched hands in discreet but sincere acknowledgement. Flags fly forever, after all.

Meanwhile, pitcher Rich Gossage tried to pick up where Nettles had been forced to leave off. “I wanted a piece of Donnie Moore so bad I would have chased him to the airport,” Gossage said. The big reliever was taken down by Atlanta’s Bob Watson, who seemed to be everywhere that day. Watson was a former drill instructor in the Marine reserves and he surely earned the brawl-equivalent of a Bronze Star for his sustained and meritorious service in the infield’s combat zone.

In both clubhouses, the growing roster of banished players had been watching monitoring events via television. As the second fracas developed, there was a pell-mell scramble back down the tunnels and up the stairs into the dugouts, with no time to get dressed.

As Gossage wormed away from Watson and took another go at Donnie Moore, the fight blew up again, and the ejected players made their return. Someone “nailed” Graig Nettles—still looking for Moore in front of the Braves’ dugout—with a flying tackle, but the third baseman escaped serious injury.

John McSherry and the other umpires waded into yet another pile and began pulling combatants apart, while the Braves’ security and ushers, reinforced by police officers, made a tight wall between the fans’ seats and the thick of the players’ battle.

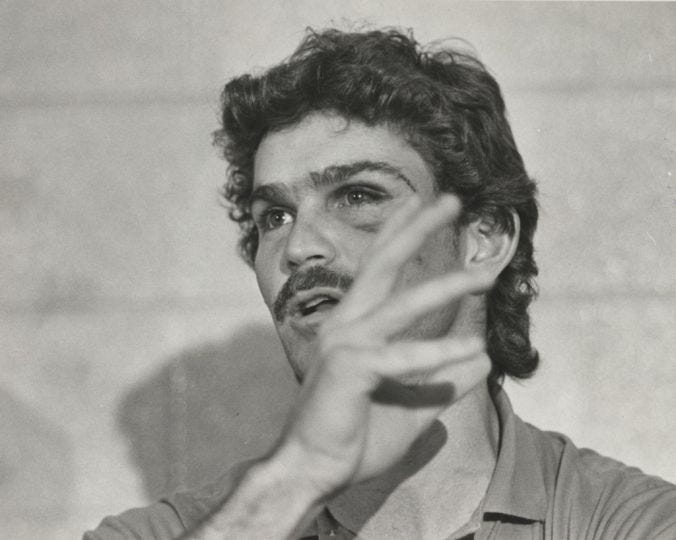

The spotlight shifted to the Padres’ dugout, where the camera found a shirtless, shoeless Padre, brandishing a black baseball bat and pointing at the fans across the roof. It was Ed Whitson, and the announcers observed that he seemed unhappy. “Boy, look at those eyes.”

Fans had begun throwing things over and through the police cordon, and the Padres wanted them held accountable. Whitson slammed his bat on the dugout roof and seemed to offer to take care of that himself.

Other Padres were making their way back to the dugout and they walked into this confrontation. Somebody hit infielder Kurt Bevacqua with a “mug” of beer (it was a plastic cup), and he snapped, launching himself onto the dugout roof.

“I don’t have to take that from anybody,” he said afterward. “I don’t care if it’s in the stands, on the field, or two hours after the game. They have the right to yell at us. They don’t have the right to possibly injure someone.” It took three security guards to keep Bevacqua out of the stands and eventually shove him back down into the dugout, partially undressing him in the process.

This moment had scarcely passed when another fan ran out onto the field, making a dash for one of the Braves’ discarded batting helmets, lying forgotten near third base. The young man was as big as some of the players, but he was nonetheless “leveled” by Atlanta’s Jerry Royster before being led away by police.

In the announcer’s booth, Pete Van Wieren was amazed. “Why in the world would any fan try to go down on the field and get involved in something like that?”

This trespasser’s actions infuriated Ed Whitson, for reasons that are not particularly clear. He tried to break out onto the field, still brandishing a bat, and had to be restrained by several coaches while someone else finally snatched the bat out of his hands.

“It was scary,” Whitson said, a decade later. “You never want to get that many people in one place riled up that much. It was uglier than you can even picture.”

“What a fiasco,” Skip Caray said on the air. “Now you’re worried about people’s safety. And for what? It’s a game. Everyone’s getting paid a lot of money.”

The umpires joined the Padres in their dugout, working to get abusive fans removed. John McSherry had had enough. The crew chief ordered all players except those involved in the game to leave the dugouts and return to their clubhouses.

“We had to start thinking about forfeiting the game,” McSherry said. “We started to worry about crowd control. The only thing I would have done differently was to clear the benches after the first fight.”

The bullpens were cleared, too, causing more delay as those players packed up. Bruce Bochy, the Padres’ reserve catcher, made one more back and forth trip in the process. “I didn’t play, but it was the busiest day of my life,” he said. “I had to run in from the bullpen for five different fights.”

As a new Braves pitcher began warming up on the mound, Joe Torre finally departed, passing the lineup card to Bob Gibson, his pitching coach. Once Torre was gone, McSherry had a pointed word with the Braves’ new pitcher, Gene Garber, likely promising to hang a forfeit on Garber if he so much as nicked the inner half of the plate.

Fifteen minutes after Donnie Moore’s only pitch of the day, the game resumed. The Padres managed to plate two runs—one of them representing Nettles—but the game ended when Dale Murphy made a marvelous diving catch in center field to seal a 5-3 Braves victory.

When it was over, the entire Braves team crammed into a small TV room off the main clubhouse to watch film of the game, and nobody was checking their batting form. “They hooted and they roared,” an Atlanta Journal columnist wrote, “they laughed. They clapped. The clubhouse had rarely been so boisterous.”

Three Braves were said to be wounded: Jerry Royster (groin); Brad Komminsk (thumb); and pitcher Rick Camp, who confirmed his injury with a vivid anecdote: “[During the fight], I kept looking for little guys and grabbing big ones,” Camp said. “Finally two of them took my legs and made a wish.”

In the visiting clubhouse, Nettles had a bruised shoulder. Craig Lefferts and Tim Flannery could compare facial abrasions inflicted by the Braves’ Gerald Perry. Kurt Bevacqua had scratches on his chest and arm, which could have come from any number of sources, including the Atlanta police.

“If Whitson had hit [Pérez] in the first,” catcher Terry Kennedy said, “the whole thing would have been over. But it took us four tries.”

Ed Whitson greeted postgame questions “with a string of obscenities.” Asked if he would have stopped if he’d hit Pérez with his first attempt, he would say only, “I don’t answer hypothetical questions.”

Dirty and soaked in sweat, John McSherry was less circumspect, but similarly “littered his comments with obscenities” as he provided the final entries on the day’s list of ejections:

Graig Nettles (SD), for fighting

Rich Gossage (SD), for fighting

Kurt Bevacqua (SD), for fighting

McSherry called the game “the worst thing I have ever seen in my life. It was pathetic, absolutely pathetic. It took baseball down 50 years.” The umpire praised the Braves security for “preventing what could have been a riot.” “How many arrests were there?” he asked reporters.

Five people had been charged with disorderly conduct while intoxicated, and one also was also charged with simple battery after kicking the shins of the officer arresting him. “Five? That’s good. I’ve never seen violence like that. It’s a miracle somebody didn’t get seriously hurt. We were very lucky.”

The umpire said he’d considered forfeiting the game but decided against it, because “I would have had to do it to the Braves because they started the second fight, and they were obviously not at fault for this mess.”

Umpires often went to great lengths to remain impartial, but after what he’d just seen, McSherry took a side. “Joe Torre handled himself excellently, better than we could have asked for, considering the circumstances.”

The problems, as he saw them, came from the Padres and their manager, Dick Williams. “We had no reason to believe Pérez was throwing deliberately at the batter—there was no provocation.” He said the intentional-throwing warning rule “basically works fine. But I assume [Williams] decided he didn’t give a damn about the rule. He decided he was going to get Pérez at any cost.”

“Dick Williams is an idiot,” Joe Torre said. “Spell that with a capital ‘I’ and a small ‘w.’ He didn’t care if he won or lost as long as he got Pérez. Once they had their shot at him, that’s it. You don’t do it all game long. He should be suspended for the rest of the year.”

“Tell Joe Torre to stick that finger he’s pointing,” Williams said, claiming that the Braves—down 10.5 games after losing the first two series—”had a meeting just before the game and maybe they thought they could scare us. But we can’t be intimidated. We will not be intimidated, and you saw that.”

Torre denied that Pérez ’s game-opening hit-by-pitch was premeditated, but to show how easy those words were, Williams did the same:

“If his pitch slipped, ours slipped all the way. We think it was totally deliberate, and you saw the results. Write what you want. We know who started it. We were the ones who went out there to finish it.”

San Diego’s manager never reappeared on the field after being ejected, and no Padre then or since has said Williams continued to direct the pitchers who threw at Pérez, but Torre was convinced he had. In describing the in-game actions of a rival manager, he triggered the rhetorical equivalent of mutually assured destruction:

It was obvious he was the cause of the whole thing. It was gutless. It stinks. It was Hitler-like action.

Some of the Padres’ postgame comments suggest Pascual Pérez’s involvement inspired Williams and the players to violate the “one-for-one” standard for retaliating against opposing players.

“Pascual Pérez shouldn’t even be in baseball,” pitcher Mark Thurmond said. “He’s been in jail four of the last five years in the Dominican Republic. He’s a coward. He ran into the dugout while everyone else was doing his dirty work. What kills me is that he got a standing ovation when he came back out. You wonder about people sometimes.”

As we saw in Part 1, Williams made similar allusions to Pérez ’s checkered resume (and added his pithy assessment of Georgia’s mustard reserves).

After the game, Pérez himself was subdued. “That wasn’t the way I would like for it to end,” he said. He’d hoped to pitch a complete game—but the rest was pretty bad, too. “I’m not a hot dog,” he said. “I pitch my game against every team. I don’t like to fight. I want to play baseball.”

The Padres walked away with a 2-1 series victory and a 9.5-game lead over the Braves in the National League West. The two teams had six games left against each other. The next series was a little over a month away, in San Diego’s Jack Murphy Stadium. In the heat of the moment, many players said they’d marked their calendars.

“I can’t see that this fight is over with,” Jerry Royster said. “Too much went on there for it to be over with. We’re looking for it.”

“They may have unleashed a wildcat,” San Diego’s Bobby Brown told reporters.

“Stay tuned for round two.”

The door’s always open, but here’s your invitation to share your own memories of this game, these teams, and baseball in 1984. We love to use comments in follow-up posts or to inspire little spin-off stories.

In the conclusion, legends weigh in, punishment is meted out, and the fans at Jack Murphy Stadium show the Braves how things are done on the West Coast.

One More Thing

Researching this story, we discovered the incredible art of Chicago-based artist Mike Noren (Gummy Arts) and may we just direct you to Gummy Arts’ merch page to take a look at their illustrated tableau of the August 12 brawl, a composition you are now able to fully appreciate!

PS-Gummy Art… very talented!!!!

Paul, how did you ever find Mike Noren’s rendering of the brawl? The wild-eyed bare-chested player was spot on. I noticed that in addition to the tee shirt, you can get it in a puzzle. Lol 😂 I am now a subscriber to Lost in Left Field and I find it is geared for people who really know baseball, but I am learning things. Meg