The Battle of Atlanta - Part 1

During the most infamous brawl in modern baseball history, the games’ unwritten rules were pushed far past their breaking point.

Here at Project 3.18, we strive to do great baseball stories justice—whether they are small and forgotten or epic and still famous decades later. We dive deep here, looking at the “before” and the “after” and featuring the small details that bring history back to vivid life.

This week, we’re bringing you the deluxe version of a notorious, fractious, record-setting baseball game. This one’s gotten plenty of coverage…but never like this.

On August 18, 1967, Tony Conigliaro—a young, talented Red Sox outfielder—stood in to bat at Fenway Park. In his third season in the majors, Conigliaro was a rising star and hometown hero having his best season yet, and his hitting strategy was well-understood: he moved as close to the plate as possible in order to reach pitches on the outer half. To beat such a hitter, opposing pitchers knew they had to push him back.

Pitching against the Red Sox that day, Jack Hamilton of the California Angels followed the playbook, throwing inside to reclaim an advantage on the outside. But in the fourth inning, he threw Conigliaro a fastball that sailed too far up and in. Conigliaro jerked back at the last second, but the ball struck him squarely in the left eye. “If you were unlucky enough to be there,” one writer said, “you will probably never forget that sound.”

One of those in earshot was his manager, Dick Williams. Williams spent 13 seasons as a player—the last of them as Conigliaro’s Red Sox roommate in 1964—but he was now a rookie manager at age 38. The young star would miss the next 20 months recovering from his injury, and though he made a heroic comeback, he was never the same.

Despite the awful outcome, Williams saw nothing nefarious in the pitch that hit his young star. “Hamilton didn’t throw at him,” he told reporters that night. “The ball just took off.”

“Gosh, I hope he’s all right,” Hamilton said. He agreed the pitch had been a mistake, adding that Conigliaro “appeared to freeze.” The pitcher decided one further piece of explanation was needed: “Nobody in the league crowds the plate more than [Conigliaro] does.”

Seventeen years later, Dick Williams was 55, now managing the San Diego Padres. On August 12, 1984, he watched an opposing pitcher hit one of his players. But this time, the manager was sure it was on purpose.

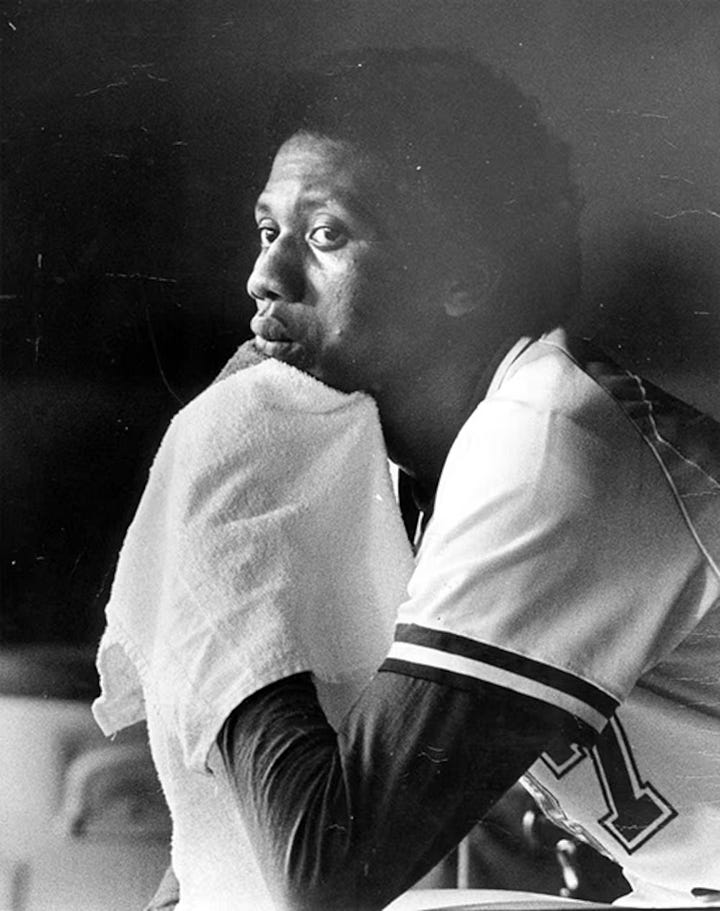

The pitcher was Pascual Pérez. Pérez was having a great season with the Braves, but he was exuberant and showy in an archly conservative game. As Williams would put it later that day: “There’s not enough mustard in the state of Georgia to cover Mr. Pérez.”

Pérez was an eccentric—a finger-gun totin’ competitor, known to check runners on first by bending down and peering between his legs, and sprint back to the dugout after ending an inning on a strikeout. Dick Williams would not have liked any of these proclivities. Nor would he have appreciated Pérez’s record of arrests for drug-related offenses, numerous enough to fill out a baseball card all their own. Seeking to establish Pérez’s guilt, Williams would bring that up, too: “All you have to do is check that guy’s background. That’s all you need to know.”

The batter Pérez hit was Alan Wiggins, the Padres’ second baseman. Wiggins was one of the best base-stealers in the game, on his way to a franchise-record 70 steals that season. In the Padres’ 4-1 victory the previous day, Wiggins had stolen a base and bunted for base hits twice, scoring once. Pérez hit Wiggins on the back with his very first pitch of the game.

Later, the pitcher said it was an accident. “I was not trying to hit Wiggins. I was trying to get inside on him. I don’t try to hit anybody, not in the first inning. I’m too good for that.”

Dick Williams didn’t buy that at all. In his view, a pitch could only wind up that far from the strike zone if somebody put it there on purpose. In his autobiography, the manager quoted a relevant passage from his version of baseball’s unwritten rules to explain his reaction:

Rule Number One: If a pitcher is trying to hit you, he throws directly behind your back.

According to writer Thomas Boswell, Williams and the Padres had two options at this point, which he explained for the benefit of readers who might be unfamiliar with the game’s unspoken bylaws:

The unwritten rules state you either hit a comparable batter on the other team or else throw at the offending pitcher in his next at bat.

However, Tony Conigliaro’s former roommate and manager did not see a choice. In his book, he saw another rule:

Rule Number Two: When Rule Number One is in effect, get the guy.

Ed Whitson was San Diego’s starter that day, and few were better suited to deliver the Padres’ response. The right-hander had an earned reputation as a battler, on and sometimes off the field. After the drilling, he and the Padres’ catcher, Terry Kennedy, huddled together in the dugout. Kurt Bevacqua, a utility infielder who played no role in the actual game that day, added himself into the deliberations.

“As soon as Wiggins got hit, Kennedy walked over to Whitson at the end of the bench and talked about hitting Royster,” Bevacqua recalled. (Third baseman Jerry Royster was the Braves’ leadoff hitter.) “I went over and said, ‘Why Royster? Let’s wait for Pérez to get up.’”

Knowing Dick Williams would have an opinion on the subject, Kennedy took the dilemma to his manager. “I asked, ‘Do you want us to drill Royster?’ And he said, ‘No. I want you to get Pérez.’”

In Williams’ long-term memory, the discussions were less explicit and the idea was entirely his:

Before my team took the field I said loudly, “We know what we’ve got to do.”

Either way, the result was the same. “There was no one else who was going to get hit,” Kennedy said. “Nobody except Pascual. He was the one.”

As Jerry Royster and the rest of the Braves’ hitters finished their at-bats unscathed, Pérez must have realized the Padres were waiting for him. His turn came in the bottom of the second inning, with one out and a runner on first.

Ed Whitson’s first pitch sailed behind Pérez’s head, missing Kennedy’s outstretched glove and allowing the runner on first to break for second. Pérez made “a threatening motion” to Whitson and both teams spilled onto the field for some perfunctory milling and glowering.

Delivering the message had two costs. The umpires had been waiting for something like this, and they took the logical step of warning both benches. Per the rules—these ones actually written down—the next pitcher deemed to have intentionally thrown at a hitter would be automatically ejected and fined, as would his manager.

Pérez struck out, but the next batter, Jerry Royster, batted in a run—which would not have scored if Whitson had aimed his first pitch to Pérez at the strike zone and kept the runner at first.

In the bottom of the fourth inning, with one out and the Braves ahead, 3-0, Pérez’s turn in the lineup came again. This time, Whitson startled Pérez and the Braves by throwing not one, two, but three pitches that tunneled inside. The rail-thin pitcher twisted and contorted his body to get out of the way. Kennedy said, “trying to hit him was like trying to hit a dancing toothpick,” but Whitson kept at it.

“It was going to happen,” Whitson said, years later. “It didn’t matter if it took nine innings or 20 innings. It was going to happen.”

The third attempt sent Pérez diving to the dirt. He came up angry, waving his bat high above his head, and Steve Rippley, the home plate umpire, quickly got in front of him as the benches cleared again.

When he was confident Pérez wasn’t going anywhere, Rippley issued the day’s first two ejections. Let’s start a running list (we’ll need it):

Ed Whitson, pitcher, for intentionally throwing at Pérez after a warning (x3, we suppose)

Dick Williams, manager, whose pitcher threw intentionally following a bench warning

Whitson headed for the showers, and Williams departed, ostensibly to his office in the clubhouse. Coach Ozzie Virgil would manage the rest of the game.

Some reports—and one entirely impeachable source—claimed that Williams hadn’t actually left.

“Williams was throwing sucker punches from the safety of the tunnel,” Joe Torre said. Torre was the Braves’ manager in 1984. “He was ordering the pitches but he wasn’t in the fights.”

The San Diego manager denied it. “My players knew what they had to do,” he said. “They didn’t need any [more] orders from me.”

Struggling to land one on Pérez, the Padres switched tactics. Whitson’s replacement was Greg Booker, who threw Pérez a garden-variety ball to walk him. Booker’s next pitch, to Jerry Royster, was intentionally wild, rolling to the wall and allowing (or, rather, forcing) Pérez to break for second base, where Alan Wiggins awaited him.

After Pérez slid cleanly in, he and Wiggins had what was later characterized as “a heated conversation.” Pérez reportedly invited Wiggins to “settle the issue” right there, but Wiggins turned the offer down, for reasons unclear. “I wish I had taken care of it then, but I didn’t,” he said after.

The Padres had now thrown at Pérez four times and driven him to Wiggins at second base—the way hounds might flush out a fox—only for the hunter to decline to take his shot.

Once again, Jerry Royster made the Padres pay for their revenge, hitting another RBI single that scored Pérez himself.

Somehow, Pascual Pérez continued to pitch well. He was still pitching a shutout when his turn came up in the sixth inning, so he batted again, leading off.

Greg Booker was still pitching for Atlanta, and he went back to basics, throwing a high inside pitch to Pérez. The pitcher was ready for it, and he ducked back. “I’m skinny,” he said. “I knew they were throwing at me. I prepared.” The benches cleared again.

Two more ejections:

Greg Booker, pitcher, for intentionally throwing at Pérez

Ozzie Virgil, interim manager, whose pitcher threw intentionally following a bench warning

For the second time that day, a new pitcher, Greg Harris, had to finish Pérez’s at-bat, under the supervision of a new manager, coach Jack Krol. Pérez hit a soft ground ball back to the mound. He took just a few steps out of the box before turning back for the dugout, not risking another trip around the bases.

Braves infielder Bob Horner watched all this from the press box high above the field. On the disabled list with a broken wrist, Horner was helping the Braves position their outfield defense. Seeing the benches clear again, he now excused himself. “I had a feeling that something would happen,” he said. He was in civilian clothes, but players out of uniform were not allowed in the dugout, so Horner went to the clubhouse and changed. “You didn’t have to see a brain surgeon to see it coming.”

By now, the Braves had compared their unwritten notes and found broad agreement: “They went too far,” left fielder Gerald Perry said. “Wiggins had his chance to get Pascual, and he let it go.”

In the seventh, a Padre finally got to Pérez—on offense. San Diego’s third baseman, Graig Nettles, hit a solo home run.

Overall, Pérez continued to pitch very well for Atlanta, and while one could think of a few good reasons to pull him, Joe Torre didn’t budge. He had to take a fourth at-bat in the bottom of the eighth, facing Greg Lefferts, a soft-tossing left-handed reliever.

With his one and only pitch of the day, Lefferts threw something like a batting-practice toss and hit Pérez on the left forearm. Perhaps the drop in velocity messed with the pitcher’s acrobatic timing.

Afterward, Terry Kennedy claimed this hit had been unscripted (he had set up for a low pitch over the plate, so that may be true). “I didn’t know he was going to do it,” Kennedy said. “I thought it was over. The law of retaliation is weird in baseball. It was bad, real bad.” It was also two more ejections:

Greg Lefferts, pitcher, for intentionally throwing at Pérez

Jack Krol, interim-interim manager, whose pitcher threw intentionally following a bench warning

This time, the players crashed together. Pérez raised his bat over his head again and was again shoved backward by Rippley, the umpire. The pitcher fell back into the safety of the home dugout. Lefferts, meanwhile, dropped behind the lines of battling infielders. Gerald Perry led a charge off the Braves’ bench, making for Lefferts. Tim Flannery, a backup infielder for San Diego, got in Perry’s way.

“I got caught in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Flannery recalled. “When Lefferts hit Pérez, I was the only one between Gerald Perry and Lefferts, so when I saw him coming, I had to get to him. In the process, Gerald and I got into it pretty good.”

Backup catcher Bruce Bochy saw the whole thing and gave his teammate high marks: “What stands out in my mind was the way Tim Flannery kept pounding Gerald Perry’s fist with his nose.”

Grown men grappled and tumbled everywhere. Kurt Bevacqua found his way to the bottom of the pile, punching down at something he hoped was a Brave. Atlanta’s Bob Watson snapped off a good-looking double-leg takedown on some unfortunate. Perry eventually broke through to Lefferts, throwing several punches that connected.

John McSherry, the umpire crew chief and a thirteen-year veteran, walked right into the thick of the action to start pulling players apart. McSherry was a large man, but he was surprised by the intensity of the conflict he found there. He soon lost his feet, falling to the ground as his colleagues rushed to help him.

“We’ve got about five different fights going on out the field,” Pete Van Wieren said on the Braves’ telecast. “Pascual Pérez is not out there; he’s gone back to the dugout.”

Champ Summers, a very large backup infielder on the Padres, was just figuring that out.

Speaking of baseball fights generally, a player once said: “On each team, there’s a couple of guys everybody wants to avoid in a brawl. There’s always a guy you know is crazy. You leave him alone.” Summers was that guy for the Padres—6’ 2”, 205 pounds, a former street brawler and a decorated Army paratrooper who received medals for bravery while serving in Vietnam.

He saw Pérez watching from safety and began shouting and pointing. “He’s hiding in there!” Summers was briefly restrained by Watson, but he waited until Watson was distracted and broke away, making a fifteen-yard open-field run towards the Braves dugout and Pérez.

He ran unopposed until the very last second, when Bob Horner, 6’ 1” 195 pounds, emerged from the dugout, dressed for the occasion.

For the first two minutes of the brawl, Horner hadn’t moved. He was injured, for one, and not even on the Braves’ active roster.

“I was really trying to stay out of it,” he said, “but when your teammates are out there and there’s the possibility of somebody knocking out one of your teammates, you can’t stand by and watch that happen. I’m not going to let him get in the dugout and get Pascual.”

Summers skidded to a stop. Without even raising his arms, Horner used the aggressor’s own leftover momentum to shunt him safely away from the dugout entrance.1

“I see that and I say to myself, ‘You are a very lucky man,’” Pérez said.

As the two prepared to grapple, the fight took a surprising turn. The next people to reach Summers weren’t players, but fans, one of whom vaulted from the dugout roof to reach him. Several fans pulled Summers down—and Horner with him—before the whole group was lost in a pile of Braves. A camera caught Summers looking up from the bottom of the scrum, and we see a man ready to make some life changes.

“In a way, it’s good a fan got involved,” Skip Caray said on the Braves’ broadcast, grasping for a silver lining. “Because it will turn all the players against the fans.”

But as the civilians were being pulled out of the pile, another fight broke out elsewhere. It was Tim Flannery and Gerald Perry II. Flannery had been briefly restrained by none other than Bob Gibson, the Braves’ pitching coach, but Flannery kept saying, “turn me loose,” until Gibson obliged him. Flannery ran right back into Perry and got the worst of the rematch, too. “I got beat up and fined $300, so, not a great day for me.”

Three minutes of brawling, five more ejections:

Bobby Brown (SD), ejected for fighting

Champ Summers (SD), ejected for fighting

Rick Mahler (ATL), ejected for fighting

Steve Bedrosian (ATL), ejected for fighting

Gerald Perry (ATL), ejected for beating up Tim Flannery

There was another delay while the Padres rustled up another pitcher and a new manager. As bullpen coach Harry Dunlop took the clipboard, McSherry and the umpires pulled him and Joe Torre aside for a conference.

Even though his team was down four runs, Torre asked McSherry to forfeit the game to the Braves. The umpire turned him down. “This ends it,” he told Torre. “One of their players was hit. One of yours was hit. I don’t want any more of it.”

Torre was still angry, but as a gesture of good faith, he removed Pascual Pérez from the game, replacing him with a pinch runner. Pérez had been thrown at six times, knocked down once, and hit once. Through all that, he pitched eight innings, allowing five hits and one run.

To get their man, the Padres had given up several runs, sacrificing the game and eight of their own. San Diego’s big closer, Rich Gossage, recorded two outs to end the inning, and the end of the game was now just three outs away.

Seeking those outs, Donnie Moore would pitch the ninth for Atlanta. As chance or fate would have it, the first batter to face him was Graig Nettles, who had homered earlier in the game.

Joe Torre reportedly warned Moore not to pitch close. The reliever let Torre say his piece, but he knew what he had to do:

“I didn’t care who was batting,” Moore said. “I was going to throw at somebody. I have to protect our hitters.”

After all, the rules on this were clear—so clear, in fact, that no one could actually see them.

Here’s Part 2, when a banished Padre returns to demonstrate to Bob Horner and the world that you can fight wearing just about anything, if you’re mad enough.

For its non-violent heroism, Bob Horner’s Stand is our favorite moment of the game. We pushed ourselves to our technical limits to bring it to you in a nine-second silent film and posted it on our Instagram. Check it out!

Great story as usual, Paul - since it took me so long to catch up, I can sample Part 2 right now.

I’m always saying to my wife as we watch football that At games end both teams shake & hug (unless your that lowlife Tom Brady) like best buds. In baseball they despise one another.

Maybe they need to listen to George Carlin’s bit on baseball/football.

Good write Paul!