The Baseball Strike of 1972

Dick Allen’s White Sox debut was pushed back by the first players’ strike in American sports history.

Dick Allen signed his contract to play for the White Sox the same day Major League Baseball Players Association voted to begin a general strike. We’ll finish our Allen story next week, but Project 3.18 isn’t about to cross a picket line, so let’s deal with the strike today.

Here’s the first part, if you need it:

No grand cause led to the first ever professional baseball players’ strike. It was a battle neither side really wanted, an index case of principles overtaking sense.

The strike happened because baseball’s owners wanted to put the players’ labor leader, Marvin Miller, in his place. Miller was the soft-spoken, sniper-eyed executive director of the fledgling Players Association. He wasn’t baseball insider or even a great fan of the game. An economist who came up in the United Steelworkers of America, Miller was a fan of the rights of workers, and he fought for those rights inch by inch, always looking for incremental gains that set up bigger victories down the road.

A long view was important to his baseball job. When he became the MLBPA’s first leader in 1966, Miller found an organization so tenuous and divided that it was called an “association” in order to placate the many players who felt joining something called a “union” was uncomfortably close to communism. Baseball had a labor/management dynamic like no other in the country, which he described in his autobiography, A Whole Different Ball Game:

Before 1966, the owners had a unilateral right to do, literally, anything they pleased; they could change the rules right in the middle of a player’s contract and say, “Here are the rules that now apply to you.”

Though soft-spoken and not particularly charismatic, the executive director was as competitive in his field as any player was in his, determined to rein in the owners, who, he felt, had kept baseball locked up in a paternalistic, one-way version of feudalism for nearly a century.

When he took over, the MLBPA consisted of Miller himself, an in-house attorney named Dick Moss, an office assistant, and a primary and alternate elected player representative from each of baseball’s 24 clubs. Led by Miller, this tiny group quickly began racking up wins.

By 1972 the minimum player salary had more than doubled, from $6,000 a year to $13,500 a year, and individual owners could no longer rewrite the rules governing their players at will. One of Miller’s key early achievements was an employer-financed pension and health care package for any player with four years of service time. This pension plan was up for renewal in 1972, once the two sides could agree on how much money the owners would put in to fund it.

The players (i.e. Miller) wanted a 17% increase in funding, to keep up with inflation, and a modest increase to cover the rising costs of health care. These were not provocative requests, but some owners, like Gussie Busch of the St. Louis Cardinals, still found a way to be offended:

I can’t understand it. The player contracts are at their best, the pension plan is the finest, and the fringe benefits are better than ever. Yet the players think we are a bunch of stupid asses.

The owners countered Miller’s pension request by offering a $500,000 increase on health insurance, but nothing on pensions. Negotiations went nowhere, but the surprise came in early March, when the owners told Miller they were reducing their original offer by $100,000. It was the bargaining equivalent of challenging the MLBPA to a duel.

The owners didn’t like Marvin Miller. He had spoiled their familial relationships with their players and filled those impressionable young heads with economic mumbo-jumbo. They were tired of seeing him rack up victories while they gave up ground, and in the pension renewal they had hit their limit.

A subset of the owners, the Player Relations Committee, handled labor issues. The PRC members believed that for all that the progress Miller had made with the players, they weren’t ready to go to the mat and strike, particularly over something as minor as pension funding. They didn’t think the players could sit at home, forgoing precious days in their athletic primes, drawing no salary, and taking a beating in the press.

And the thing was, Marvin Miller felt the same way.

Striking would be a huge gamble, and Miller was not a betting man. He worried—correctly—that the press and public were apt to see the players as greedy if they stopped baseball over such a marginal dispute. Pension funding didn’t sound like a cause that could light 600 torches and keep them burning for months. And there was no strike fund to support the most vulnerable among the membership against a pack of dug-in millionaires.

All things considered, Miller believed the pension fight might need to wait, but he did what a union representative was supposed to do in such a moment. That spring he went from camp to camp, explaining the pension stalemate and asking each of the 24 clubs to vote to authorize a strike.

In the language of labor relations, a vote to authorize a strike is different than a vote to strike. The former is more performative, a demonstration that the union is behind its leadership. A low-stakes show of solidarity couldn’t hurt, Miller reasoned. Maybe the owners would blink.

The players voted 663-10 to authorize a strike. Miller had his show of support, but the owners were unimpressed.

In a meeting on March 22, the owners agreed that if Miller wanted more of their money, he was going to have to show his cards. The group also agreed to keep their decision out of the press, but Gussie Busch didn’t do discreet, telling reporters:

We voted unanimously to take a stand. We’re not going to give them another cent. If they want to strike–let ‘em.

The player reps tacked that quote up in every clubhouse in the Grapefruit and Cactus leagues.

On March 31, the old pension agreement expired and it was clear Busch had not exaggerated; the owners weren’t backing down. “How do we get out of this pickle?” Miller asked Moss. They both agreed a strike was the wrong move, so they drafted a face-saving letter that punted the issue into 1973.

At their March 31 meeting in Dallas, Texas, Miller read the 48 player reps his letter, which he couldn’t send without their approval. He downplayed the significance of the pension issue. He assured them they could take another run at it later.

“There are just some times,” he told the players, “when you tuck your tail between your legs and accept what [the owners] have to offer.” This was just how it went in the give-and-take world of labor negotiations.

“Well, screw that,” Tim McCarver (Phillies) said.

“Dammit, there are just times when you’ve got to stand up for your rights,” Reggie Jackson (Athletics) said.

Thirty hands shot up. Player after player rose to try and persuade their labor leader to back a strike. Miller realized he was standing on a runway in front of a plane trying to take off.

Jay Johnstone, one of the White Sox’ reps, said that Miller pleaded at least 10 times during the reps meeting not to vote for a strike unless there was complete unanimity.

“It would be a terrible mistake to start something you’re not prepared to finish,” Miller warned.

“I don’t think Miller wanted a strike,” Johnstone said, “but on the first vote 21 of the 24 clubs voted to strike immediately. The other three wanted it later. Finally all 24 agreed to strike.”

When the final vote was cast, the reps voted 47-0 in favor, with one abstention.

The players began banging their hands on the conference table and chanting “Strike, strike, strike!” Miller found it almost comically dramatic, but he could see the players’ feeling was real. He held up his hands, signaling defeat. They would strike.

Looking back on it, Miller realized he’d succeeded in making a professional union out of the players much sooner than he thought. A steady diet of labor education and a series of bargaining wins had unified them and shown them the power of working together. And while they were relatively new in this game, the players were going to keep swinging until the owners made an out. This was the only way they knew how to play.

The striking players began walking out of spring training. Most scattered to the winds to work closer to home, though some, like Dick Allen, chose to stick around. Told the White Sox’ Sarasota practice facilities had been closed due to the just-opened strike, Allen was unbothered.

“That’s okay. I’m from the country. I learned to play on a hillside. I’ll find a place around here somewhere.” An hour later Allen had recruited a college pitcher and was taking batting practice on a local field.

The owners and executives were shocked to hear that the players’ had gone through with it. A work stoppage was certain to cost them millions of dollars in lost revenues, far more money than the amount at stake in the underlying dispute. They had convinced themselves that Miller was “shooting blanks” when it came to such a major action, and now they blamed him for leading the impressionable players into this foolish position.

Which isn’t to say they let the players off the hook. Many executives felt, not incorrectly, that they often went out of their way to take extra care of the players, helping them out with advances, loans, and other favors. When the strike began, the perk party ended.

It had long been the Detroit Tigers’ custom to let the players ship their belongings north on the team equipment trucks, and as the camps shut down some of the Tigers’ players came by to drop off their things. An unbelieving Jim Campbell, the general manager of the Tigers (who we last saw being a real killjoy in 1980) came storming out of his office.

“These guys are on strike,” he yelled at the workers loading the trucks. “Get every damned thing of theirs off this truck.” Campbell turned to the disbelieving players:

If you’re not going to play, we’re not going to take your goods to Detroit. We’ve been good to you all this time. Now Santa Claus is dead!

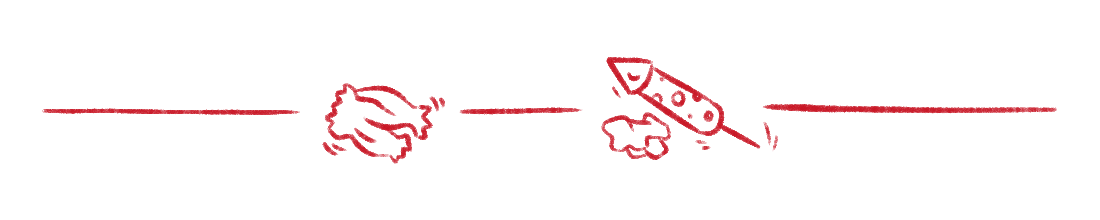

These were the hostilities Miller worried the players would have a hard time shrugging off, but he was reassured by the words of Willie Mays, who, in the twilight of his great career, unexpectedly found himself a player rep.

Being a rep was a risky assignment. Of the 24 primary reps in 1971, 16 were traded or released from their teams within the year, and both the Mets’ primary and alternate reps had just been traded away. The Mets’ players hoped Mays had enough stature to protect him from the reprisals that befell his predecessors.

“I know it’s hard being away from the game and our paychecks and our normal life,” Mays told the player reps a week into the strike.

I love this game. It’s been my whole life. But we made a decision in Dallas to stick together. This could be my last year in baseball and if the strike lasts the entire season and I’ve played my last game, well, it will be painful. But if we don’t hang together, everything we’ve worked for will be lost.

The players’ collective poker face quickly unnerved the owners, whose costs were piling up higher and more quickly. The owners sent Miller a new offer, adding $400,000 for both the pension and the health plan, respectively. Miller turned it down.

Gussie Busch suggested the owners make a pool of $1 million to support some of the poorer clubs. Walter O’Malley of the Dodgers testily replied that his team alone lost a million every weekend the strike went on.

Busch’s concerns were well founded. By the second week of April at least three clubs were already so short on cash that they were preparing to close their farm systems and release minor league players. One of those teams was the Chicago White Sox, who began cutting minor leaguers in the second week of April.

The White Sox’ owner was a quiet man named John Allyn, who disliked seeing his name in the papers. But with his feet closest to the proverbial fire, Allyn made a splashy defection when he opened Comiskey Park for the use of any players who wanted to work out and practice there during the strike.

Allyn soon received a sharply worded instruction from American League president Joe Cronin telling him to cease and desist, but the Sox’ owner wasn’t having it.

“This thing never should have happened in the first place,” Allyn said. “And nobody is going to tell me what to do with my team.”

This was the owners’ tragic flaw. They were 24 supercharged egos used to getting their way, and a few of them were always pulling in the wrong direction and undercutting the efforts of the majority.

Meanwhile, Miller kept on the move, updating groups of players and keeping spirits up. The player reps were an essential glue, organizing group workouts across the country and arranging for more than one star to host update meetings and open his home to younger players needing a cheap place to stay. The Minnesota Twins’ Jim Perry (Gaylord’s brother) devised a whole system including transportation and distributing regular updates from the union.

Unlike the owners, the players had to work together as a team every day, and if they didn’t follow instructions, it usually meant their jobs. These proved to be transferable skills.

During the first few days of the strike, Charles O. Finley, the owner and operator of Oakland’s Swingin’ A’s (and erstwhile advocate of the three-ball walk), was firmly in the hardliners’ camp. Finley’s “not one red cent” position certainly seemed in keeping with his combative personality (and notorious frugality in individual contract negotiations), but by the 10th day of the strike, Finley’s tone had changed:

Both parties are at fault and both sides must strike a compromise. This strike must end immediately. It’s a disgrace to sports.

Many of his peers resented the change of heart, calling Finley “irrational.” In reality, he’d realized he’d made a mistake and was now trying to correct it.

His epiphany came at an all-owners meeting on April 10, when a consultant hired to advise on the strike distributed a chunky report that contained pages of information on the players’ pension funds and related actuarial information. The consultant said the reports couldn’t leave the room, so the owners could only give the report a quick once-over. This was dry, dense stuff, even for a room of businessmen.

Only one among them could flip through such a report and understand what it said—the one who had made his fortune in the medical insurance industry. For once, Charlie Finley was the insider:

The other owners didn’t understand what it was all about. I was adamant in standing pat on our original offer, but I was standing pat because [I didn’t have all the facts].

Now Finley did have the facts, and they revealed a surplus of interest money just sitting in the pension fund. By his reading, the owners could use this to largely give the players what they wanted without having to put down much new money. It was a way out.

Finley began clamoring for another meeting where the owners could override the PRC hardliners who were handling the strike negotiations. He flew to New York and harassed Joe Cronin and commissioner Bowie Kuhn to put something on the schedule.

That meeting took place on April 13. Hearing Finley’s bookkeeping solution and spurred on by Allyn and the other peacemakers, the owners voted to support a new offer to the players. They would contribute an additional $500,000 towards the pension, a move that essentially satisfied Miller’s initial request.

The end came on April 13. After several discussions on what to do about the struck games went nowhere, everyone agreed to just drop them and move on. With the extra time lost haggling, a total of 86 games were wiped out. Each player lost about 5.5% of his salary for the year, but the owners collectively lost $5 million in revenue from the scrapped games.

“Nobody won,” commissioner Bowie Kuhn said. “The players suffered, the owners suffered, baseball suffered. I hope we’ve all learned a lesson.”

“I think it’s fair to say nobody ever wins in a strike situation,” Marvin Miller said. “This one is no exception. We’re not going to claim victory, even though our objectives were achieved.”

“Both the owners and players are now aware of each others’ strengths,” said White Sox outfielder Rich Reichardt, the team’s new player rep (the incumbent had been released). “The strike was more an issue of principle than money.”

In his post-mortem in The Sporting News, prominent baseball reporter Jerome Holtzman cut right to the heart of the strike:

The owners’ biggest mistake was that some of them thought they could break Marvin Miller and the association. This only proves to me that these owners don’t know what’s been going on and actually believe all the propaganda that Miller is some sort of Svengali who holds an evil and sinister power over the players.

To think this is to believe that the players are merely country-boy boobs who are being led against their will. This has never been true.

When the strike ended, players scrambled to meet up with their clubs before the season began on April 15. The White Sox would begin with three games on the road in Kansas City, but the team came together in Chicago for a final practice on April 14.

Dick Allen was there on time and joined his Sox teammates for a two-hour workout. Everyone was eager to see how Allen looked after missing most of spring training.

Donning the White Sox signature cherry-red and whites, Allen showed no sign of self-consciousness or rust. His 15 minutes in the batting cage drew a crowd and despite temperatures in the 40s and a stiff wind coming in off nearby Lake Michigan, Allen ripped home runs into the empty Comiskey bleachers with an ease that startled some of his teammates. The wait was over.

Next week we’ll finish the story of Dick Allen’s smashing White Sox debut.

On April 21: Handshakes all around.

One More Thing

If you’d like more about baseball’s incredible labor revolution, here are three books that cover the tale in stimulating fashion, all of which we drew from in writing this piece:

A Whole Different Ball Game, by Marvin Miller

Hardball, by Bowie Kuhn

The Lords of the Realm, by John Helyar

I would add Ball Four, or at least the introduction/first chapter, to the reading list as an illustration of what it used to be like. Jim Bouton was literally putting on his uniform at the beginning of his rookie year and they put a contract in front of him and said “Here’s your contract; you have to sign it before you go out there.” He went out and won 18 games and they tried to do the same thing the next year.

Can’t wait for #2.