Scrap Metal Children - Part 2 of 2

In which two kids shell out to see a baseball game

We are back with the finale (and the forfeit) of this World War II baseball story. Some tales of baseball in wartime are about unexpected heroics and Hall of Fame characters, but this isn’t one of those. However, you will discover just how many old toasters it takes to build a heavy cruiser.

If you need Part 1, here it is!

The end of the New York Giants’ 1942 season was altogether an exercise in questionable planning.

The team was already scheduled to play three doubleheaders in their last four days, and then poor weather caused the postponement of a September 20 twin-bill with the Braves in Boston. The only way the teams could get those games in was to play them at New York’s Polo Grounds at the very end of the season. Arriving for the final homestand, then, the Giants’ schedule looked like this:

September 24, doubleheader against Philadelphia

September 25, doubleheader against Philadelphia

September 26, doubleheader against Boston

September 27, doubleheader against Boston

Eight games in four days, not how you really want to do it. It could have been an opportunity to mount a breathtaking charge up the standings by the third-place Giants, except that the Giants began the homestand 18 games behind the second-place Dodgers. Nothing doing there. The National League was extremely top-heavy in 1942, with the Cardinals and Dodgers winning well over 100 games apiece and beating up on everyone else in the process. The Giants were the only other team to finish with a winning record. And the Braves, well, let’s just say they looked up at the Giants with binoculars.

So this would be baseball for the sake of baseball, for the fun of it, for the fans, and for many of the players, a last chance to enjoy the game as they prepared to say goodbye and depart into military service and uncertain futures.

The Giants returned from the road to find the New York City scrap drive just getting underway. The rival Dodgers were a few days into their scrap promotion (but still a few days before the Scrap Metal Children roughed up New York’s Finest on September 25).

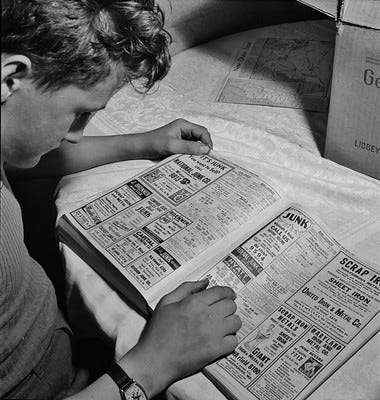

Kicking off their ultra-mega homestand, the Giants announced that they would join the Dodgers and trade scrap for tickets, and given their schedule, ten pounds was worth two games. Fans would drop their scrap at the Polo Grounds’ entrance at 159th Street and Eighth Avenue to receive their entry pass.

Thursday’s doubleheader with the Phillies opened the scrap drive. With no hope of overtaking the Dodgers (which would have meant more money and therefore a reason to try), the Giants’ player-manager, Mel Ott, “tried a couple of experiments” in the day’s lineup, “with moderate success.” Ott inserted some rookies, proverbially “letting the kids play,” and the teams each won one game.

That first day of scrap donations yielded 556 entrants bearing nearly three tons of scrap. The Giants also admitted 163 uniformed servicemen for free, but even with all these giveaways, the day’s total attendance was under 4,000, typical enough for the lame-duck circumstances, even in populous New York, which divided fan interest across four different teams.

The next day was September 25, and the New York sporting press was far more interested in what happened in Flatbush that day. The Giants split with the Phillies once again, collected some unknown amount of scrap, and played in a nearly-empty ballpark.

On September 26 the seventh-place Braves replaced the eighth-place Phils. And while the competition wasn’t any more appealing, September 26 was a Saturday. For the first time since the Giants returned, school was out.

As the Giants sweated through their double-time march, the city of New York made incredible progress operationalizing the scrap drive.

New York’s eminent newspapers were less pushy than the Sacramento Bee and the Iola Register, but their pages were similarly-filled with scrap coverage, which was followed almost as a new major league sport.

The country’s largest city was eager to go big in the effort, but there were whiffs of opportunism. New York generated a list of 49 buildings, including unused schools and antiquated firehouses, all “suitable for demolition” and scrap retrieval, and could the War Production Board perhaps help pay for that?

The biggest “charitable” project centered on the Giants’ own backyard. The city’s Board of Transportation sought to harvest about 7,000 tons of scrap from old elevated train storage yards near the Polo Grounds. The old cars stored there would be spared, per an Office of Defense Transportation order to preserve such cars for possible war use, serving as transport for workmen to be shuttled between industrial yards and war plants and nearby planned communities. The storage yards stretched from Coogan’s Bluff to the Harlem River.

On one day across one four-block radius, New York households donated about 14.5 tons of junk, “including vacuum cleaners, sleighs, golf sticks (sic), loving cups (?1), and baby carriage chasses.” There was so much stuff that the volunteer truck fleet to move it all was overwhelmed and the drive sponsors had to call in the Army to help clear the streets. Projected across the whole city, organizers expected to get about 35,000 tons out of New York residents, an average of about ten pounds per head. This per capita figure was twice what a similar effort in Seattle yielded.

35,000 tons of scrap would essentially help put two brand-new battleships in the water, or 2,500 tanks, all from one pass through one city’s closets, garages, and kitchen drawers.

And there was the obligatory highlight reel of strange miscellany, which peppered every scrap report because, and we agree, compiling them was quite fun. New York’s list of creative donations was extremely New York:

A collection of theatrical costumes, “heavy with metal,” was turned over by the Brooks Costume Company.

The Philharmonic-Symphony Society turned in 1,000 pounds of worn-out instruments and “other orchestral gadgets.”

One large apartment building turned in 135 pounds of keys.

Heavy steel bars from New York’s Sing Sing and the notorious Tombs prisons were donated, yielding a total of around 100 tons. Prison scrap, the New York Times helpfully informed its readers, was of a high grade, as such metal was built to resist the hacksaws and files smuggled in by prisoners. We learn every day.

The exclusive Hotel Astor was holding a “tin can ball” where entering society types would be required to donate ten cans for salvage (in addition to having paid for their ticket; this was a class event, not a baseball game).

But our favorite was the donation of “three ancient, smooth-bore cannons, weighing three tons, discovered in the hold of an old freighter in dry dock, where they had been used as a part of the ship’s ballast, along with a quantity of chains and rocks.” Museum experts suggested the cannons were forged sometime around the War of 1812 and now they were headed back to the front.

One sharp-tongued out-of-towner wrote the Wall Street Journal to suggest another creative resource, saying, in part:

Look at the old, dirt-collecting statues all over the country—especially in New York. Everywhere one turns there is a statue of this or that—not a soul has ever derived any benefit of them, unless possibly it was the sculptors. Walk through Central Park any day. Look at the statues; read the inscription telling you what this particular hero did. You probably never heard of him.

At first we felt this suggestion was egregious and petulant, then we looked at the list of Central Park statues. Even setting aside those installed since 1942, it is a very long list of metal statuary, and there is at least some low-hanging fruit. For example the park has two sculptures of bears, and neither bear seems to have done anything remotely heroic. Nonetheless, they and all their ferrous brethren survived the war unscathed.

The paid attendance for the September 26 Giants/Braves doubleheader was 2,916 persons, but this figure was highly misleading. As always, people who got in without providing money were not counted in the “paid attendance” reporting, meaning to understand how many “non-paying” fans attended that day after donating scrap metal, we have to do a little math.

Afterward, the Polo Grounds scrap pile held 56 tons of stuff, including the hollowed out shell of an automobile; that donor had presumably also paid for several friends. That overachiever aside, if we assume that most entrants brought the minimum of ten pounds, some arithmetic suggests that around 11,200 people paid with scrap, and according to newspaper accounts, the large majority of these uncounted seemed to be youngsters. The Associated Press suggested that many of them had never actually been out to see a baseball game before, doing the thing newspapers used to do all the time where they made specific claims without elaborating or providing any evidence.

Our best guess is that for some of New York’s poorest children, even the modest price of a ticket was typically out of reach, but a scrap metal donation, they could do. Flush with trash and freed from their studies, they made their way to the Polo Grounds for a lifetime highlight: seeing the great Mel Ott and his team of Giants with their own eyes on one of the last days before who knows what would happen.

Made an offer they could not refuse, some 10,000 kids dropped off their scrap outside the spectacular eminence of the Polo Grounds on a cool day in early autumn and made their way inside to baseball heaven.

The games had two assigned umpires, Ziggy Sears and Tommy Dunn. This would have seemed like a rather sleepy assignment as the season wrapped up, but one wonders what Dunn and Sears said to each other as they got a look at the demographics of the larger-than-normal crowd filing in. The Giants won the first game 6-4, beating the Braves’ starter, Bill Donovan, who was replaced by rookie Johnny Sain, pitching out of the bullpen as his first year in the majors came to a close.

This contest was “steeped in Giants lore,” according to the Daily News, providing sensory riches for children used to listening on the radio.

Mel Ott, the Giants’ player-manager, hit a home run, and the team’s other great hitter, Johnny Mize, made four hits, including a home run of his own. The Giants started the legendary Carl Hubbell, one of the greatest stars of the Depression era. 39 years old and at the close of his 15th season, Hubbell was just 12 games away from the end of the line in 1943. In his final start of his last full season, King Carl came away with the win, his 249th.

Game 2 also featured a Hall-of-Famer on the mound, but no one present knew that at the time. That day, Warren Spahn made the fourth appearance of his rookie call-up and only his second start, facing off against the Giants’ Bob Carpenter.

The Giants tagged Spahn for two runs in the first inning and another in the fourth. The score was relatively close, 3-1, until the seventh, when New York added another two runs.

The Braves got one run back in the top of the eighth, but the game still seemed well in hand for Carpenter and the Giants, with Warren Spahn on his way to the first decision of his career, a loss. But then, as the Giants walked off the field in the middle of the eighth, the Scrap Metal Children returned in a gleeful torrent.

“Casting aside all adult restraint,” thousands of children came tumbling out of the stands, engulfing all before them, including the Braves trying to take their places in the field and the Giants trying to get back into their dugout.

Everyone was caught up in a maelstrom, the Times reported, “a hopeless, tangled confused mass of children, running helter-skelter all over the field.”

Umpire Ziggy Sears fought his way to the Giants’ dugout and “took quiet counsel” there. He ordered the stadium’s public address system to warn the crowd of an incoming forfeit, but this was a primitive speaker system and no one could hear it above the joyful shrieks emanating from the diamond.

To their credit, the Braves were willing to wait it out, but with police, special cops, ushers, and grounds crew unable to make even a dent in the swirling, squirming crowd, this proved impossible. Without a playable field, Sears declared a forfeit by the Giants, throwing the game to the hitherto-losing Braves.

It was the first official forfeit since 1937. The league decided to retain all records from the almost-completed game, except, as was custom, the identification of a winning and losing pitcher, taking Warren Spahn off the hook.

If not for the forfeit, September 26, 1942 might have been (if you squinted) the first time both Spahn and Sain were beaten on the same date, but “the charge of the scrap brigade” kicked that milestone quite a ways down the road. As Mark Twain said, history does not repeat, but it rhymes, and we love pointing such couplets out when we find them.

So, why did they do it? What sent these children so amok? The day’s coverage offered only a few stray leads. One paper thought the kids’ desire to see their heroes up close overwhelmed them, first a few and then many hundreds and thousands more, on the eve of so many departing into the service. Johnny Mize, for one, would not appear again at the Polo Grounds until the war was over.

Another account suggested a small group of eager fans planned to rush the field at the end of the game, but then forgot or misunderstood what inning it actually was and jumped over the walls prematurely.

But, compared to the gallons of ink being spilled on what somebody found in the ballast of an old ship, the Scrap Metal Children came and went pretty quickly. Quotes of any kind were a rarity in this age of sports journalism, even though quotes regarding an event like this would seemed to provide easy comedy. The only public reaction we could find came from the Giants’ owner and president, Horace Stoneham.

“It was an unfortunate ending,” Stoneham said, “but there was no alternative in the circumstances. We will continue to admit the youngsters bearing war scrap, but we will try to marshal them in restricted sections tomorrow for our final double-header.”

Stoneham’s patriotic resolve was admirable, but futile. Sunday’s make-up doubleheader was rained out, retroactively making the children’s unexpected party the season’s end.

The Giants’ scrap haul stood at a modest 60 tons, with one major highlight, reported by the United Press.

Before the game, two young boys, identified as Rosco Laso and Gus Pemaganio, were poking around in a basement trying to scrounge up their fee for the September 26 doubleheader, when they came upon something that looked ideal. It was smooth, round, portable, and inarguably made of metal. They lugged it down to the Polo Ground and proudly unveiled it, inadvertently causing a brief burst of excitement in an otherwise orderly process.

The scamps had brought a 155 millimeter artillery shell, left over from World War I.

The Giants’ players spent the unexpected free day clearing out their lockers and saying goodbyes, which were delivered “laughingly, noisily, and good naturedly,” and with more emotion than usual. The players knew that “until next time,” would not cut it as they departed to face the realities of wartime. Some had already enlisted and were in a rush to get home to see family and friends for yet another round of goodbyes before they reported to training bases.

The first Giant into service would be sworn in to the Marine Corps the very next day. Willard Marshall, a promising outfielder brought up by the team, would be training at Parris Island before the World Series even got started.

The Giants would be among the major league teams most depleted by wartime military service. If we look at just the players that started in either of the two games on September 26, the losses are vivid.

Out of eleven starters, a whopping seven of them would be enlisted or drafted and away from the team by 1943. Mel Ott arrived at Spring Training that next season to encounter a team he hardly recognized, a bad sign, and the replacement Giants ended up in last place.

Across the diamond, the Braves fared better by the numbers, but lost both Spahn and Sain for three seasons. Pray for Rain would have to cover a lot of innings in the war years.

Many players wound up playing baseball during their service, just in different uniforms, for the same reasons that led Roosevelt to keep baseball going in general. But there were some notable exceptions, including Warren Spahn, who enlisted in the Army and served as a combat engineer, seeing hot action across Europe including serving during the Battle of the Bulge. Spahn began what would become a gaudy collection of awards with a Purple Heart and a Bronze star.

In mid-October, the scrap push was in its late innings. Americans from Iola to Queens were doing their part, spurred on by the government and the various private constituencies it had deputized: the newspapers, the high-society philanthropists, and the baseball teams.

By October 17, New York had gathered 113,711 tons of scrap. The city estimated 150,000 tons would be collected. Manhattan’s yields were up to an average of 26.3 pounds for each of the borough’s almost 1,900,000 residents.

Using some very rough figures, New York City alone had generated enough scrap to cover the major naval losses at Pearl Harbor, including four battleships sunk and another four damaged. The United States’ economic and industrial power was the real reason Churchill had inwardly declared victory the moment America was ambushed into the war. Japan had put enormous effort into a first-strike on Pearl Harbor, and less than a year later, just one city in America had made up the difference out of keys, golf sticks, and old cars, without even dipping into its plentiful reserve of bear statues.2

The British leader was right, of course. America had economically and materially supported the Allies before even entering the war, but once it became a combatant, the rain of materiel became a deluge. When the Americans and Soviets closed in on Berlin from separate directions in 1945, both armies moved on fleets of American-made trucks.

Forfeits often prompted dark ruminations on the decline of societal norms, particularly in the nation’s youth, but the Scrap Metal Forfeit might actually be the one time where the opposite happened. These kids, like their Brooklyn neighbors, supported the war effort and sure, they got a little overeager to see their heroes one more time and maybe had a little too much fun as a result. Good for them. With the portents of war looming everywhere, the spectacle of unsupervised children frolicking with their baseball heroes on the storied lawns of the Polo Grounds was a welcome sight for the country, reminding New Yorkers and Americans what was worth fighting for.

Now that’s what I call a forfeit.

Two down!

Next week, we’re going to add a few updates to some of our earlier stories. Wait, how could there be updates to stuff that happened fifty years ago?

Imagine a community Easter egg hunt in a park, and the kids come through and scoop up a thousand eggs in five minutes, but a few hours later you walk your dog through the aftermath and spot a few eggs that got missed in all the commotion. Well, it’s like that, except here the candy is Johnny Bench wearing hot pants, a half-hearted stab at reviving Metsomania in 1970, and some words from the one and only guru of forfeiture.

On May 13: Frownfelter speaks!

If you know what a “loving cup” is without Googling it, let us know (tactfully) in the comments so we can all appreciate how smart you are.

In fact, six of the eight American battleships damaged at Pearl Harbor, including two that sunk, were actually raised, repaired, and by 1944 were busy in the Pacific theater doing very compelling Jason Voorhees impressions. No wonder Churchill had gotten so excited.

I knew a loving cup to be a trophy but never knew of it being passed around at weddings to all to drink from it. You learn something new every day! Interesting read today.

Seems like I am always learning something new from 3.18. Thank you Paul