Postscripts - Vol. 3

We uncover a hypnotist-for-hire and the galoshes history forgot, play hype-man, and tell a story with a reader!

Happy New Year, everyone!

In a fully-optimized world, this probably would have been our last entry of 2024, but we ran out of calendar, so let’s take one last look at 2024 and then turn off the lights and lock the door behind us.

Whenever we find a good nugget related to a previous story, we make a note, and wait for the pile to topple over into a Postscripts piece. This time, we also ended up discovering a few leads that will surely lead to future stories, so consider today’s entry both dessert and appetizer.

Postscript: These Boots are Made for Walking

Recommended Readings:

Looks Like Rain, Sensible Send-offs (for more on Luther Taylor)

By now our regular readers know how much Project 3.18 loves a good catalogue of the absurd, and we keep a careful eye out for additions to our various inventories. All the way back in April we wrote about rain-related ejections, including several in which rain gear (and a small dugout fire) were used to colorfully illustrate a point.

Well, we found another one!

On a rainy June day in New York City in 1908, the hometown Giants were to play two games against the Cincinnati Reds. The first game began at 2:15 pm amid steady showers, but after two innings, “the rain came down in torrents.” Both teams were prepared to call it a day, “but Umpire Johnstone decided the game must be played under any weather conditions that might arise.”

“Umpire Johnstone” is Jim Johnstone. Hold onto that name, because it is one you’ll be hearing from Project 3.18 again in the future, because Johnstone is at the center of a wild forfeit story involving the Giants, a debacle that took place a few weeks prior to this rainy day with the Reds. As a result, there was quite a lot of lingering bad blood, and Johnstone’s insistence that the players continue in a driving rain is very much of a piece.

The Giants found Johnstone’s decree absurd, and in the third inning, Luther Taylor–one of New York’s pitchers as well as a part-time coach and full-time umpire-baiter–came out of the dugout “wearing Grounds Keeper Murphy’s rubber boots.” Johnstone “failed to see the joke that was plain to everyone else,” and Taylor was “sent to the clubhouse” and would later be fined $10 by Harry Pulliam, the National League president.

Well, that sounds like an ejection…but it’s not present on the Retrosheet ejection index…why might that be?

The Giants pulled ahead after Taylor was chased, and threatened to pull further ahead in the fourth when, all of a sudden and for no particular reason at all, Johnstone abruptly changed his mind, calling a halt to the proceedings. Readers of our most recent forfeit story will recall that for much of baseball’s history, a game that ended before five innings could be finished was rubbed right out of the records, to be fully replayed on another day. Johnson did what he did to erase the Giants’ early lead and likely win, and in doing so he also erased all records from the first four innings–including Luther Taylor’s rain boot ejection.

Postscript: The Times They Are A-Changin’

Required Reading: A Haunted Player

For Halloween, and also, we suppose, for National Lifeguard Appreciation Day1, we told the eerie, surprising story of Billy Earle, a 19th century catcher of some notoriety in his day. In his early years, Earle dabbled in the pseudo-mystical science of hypnotism and for this he was eventually shunned by superstitious and fearful teammates across a dozen different professional teams, who feared that hypnotism had cursed him and/or gave him the power to curse his opponents.

Fast-forward to March 1979, where we check in on the state of hypnotism and baseball at the White Sox spring training camp.

Headline: “Sox Boss Not Dazzled by Hypnotist”

It was early in the spring schedule, and many Sox players had the day off as non-roster and minor-leaguers filled in during the day’s game against the Blue Jays. Taking advantage of the free time, the White Sox’ designated hitter, Ron Blomberg, met beyond the right field fence with a “stout fellow” named Harvey Misel, who was essentially serving as the White Sox’ (unsanctioned) team hypnotist.

Don Kessinger, the team’s player-manager, was displeased, calling “a session of his own” with Blomberg later that day to review some ground rules.

“I have no objection to what players do on their own time,” Kessinger said, “but there will be none of that while they are wearing the uniform of the Chicago White Sox. Maybe something like this is good, and if it turns out that way I’m all for it. But, quite frankly, I’m not excited about it right now.”

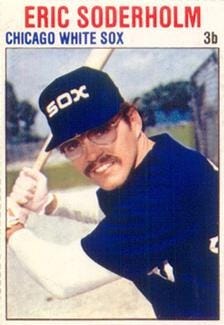

Full disclosure: for now, we know nothing about Harvey Misel beyond what this article reports, but he seems to have gotten on the radar of major league players as early as 1975, when he helped the Minnesota Twins’ star, Rod Carew, recover from serious knee surgery. Far from running Carew out of town in horror, nine other members of the Twins, including infielder Eric Soderholm, were mighty impressed. “Rod went to him for confidence, relaxation, and to alleviate the pain in his knee,” Soderholm said in 1979. “Any time a superstar tells you he’s doing something, everybody wants to try it.”

Billy Earle, the Little Globetrotter, could attest that this had not always been the case.

Fast-forward to 1979. Soderholm is now a member of the White Sox, but he had remained a client and friend of Misel. Soderholm was apparently an even better hype man than Rod Carew—the Chicago Tribune reported that 18 members of the White Sox roster (and four non-roster invitees) were attending one-hour hypnosis sessions with Misel that spring. Misel reportedly disliked the “showmanship aspects” of hypnotism, but he had once made Jack Kucek, one of the Sox’ pitchers, “so rigid that he could be supported by head and feet between two chairs.”

Misel had already met with Blomberg earlier in the week but the hypnotist scheduled an impromptu follow-up because “it’s best to have the suggestions he gives you reintroduced from time to time,” Soderholm said. “I try to see him once a week or have Harvey talk to me via phone.”

Soderholm, a third baseman, had been a key member of the White Sox in 1977 and 1978, and the Tribune reporter, Richard Dozer, tried to find some sympathy for his embrace of what Dozer characterized as “gimmickry,” explaining that Soderholm had suffered a devastating knee injury of his own in 1976, followed by a long, setback-filled rehabilitation in which the infielder tried “everything from bodybuilding to faith healing.”

Soderholm said Misel had kept him under “a spell of positive suggestion” for the past two seasons, “but with no outward evidence of a trance.”

This feels like the start of a future Project 3.18 story, doesn’t it? Rod Carew…at least 20 other players…and a stout hypnotist who seems to be cornering the market on the American League West. Watch this space.

Postscript: Seeing Red

Required Reading: The Doctor

Whenever we write about a player or game some of our readers may have seen, we love to hear from you. We hoped that Gaylord Perry’s several decades of service time might prompt a response or two and well-traveled reader MATT answered our call, adding a wonderful coda to our account of Perry’s psychological war against opposing batters:

I saw Perry pitch for the Yankees in August 1980 vs the Mariners. He wore a red glove and Mariners manager (Maury Wills) made a stink about it since it wasn't black, brown, tan, or a team color. Game may have protested; can't recall. Umpires let Perry continue using the glove...I guess because red is a team color (see Yankees top hat logo.) Anyway, a fun night in the Bronx!

August 30, 1980 was indeed a fun night in the Bronx, because 40,000 fans (including Matt) enjoyed a 9-3 Yankees victory that kept them atop their division and on course for a playoff berth.

Gaylord Perry had only been a Yankee for a few weeks, having been traded from Texas to New York on August 13 to help during the latter’s playoff drive. The pitcher was having a down year, but still effective enough at 41 years old. And he still played the hits:

Before every pitch he throws, Perry goes through elaborate motions with his fingers on his forehead and cap, obviously designed to distract hitters.

But—as Matt noted—the drama on August 30 had nothing to do with the ball. That night, the problem was Perry’s red glove. “I wanted to make it white, but the rule wouldn’t allow that,” he said. Ordered while he still played for the Rangers, this was the red glove’s 1980 debut, and after seeing it for one inning, Seattle’s manager, Maury Wills came out to protest, arguing with home plate umpire Joe Brinkman for “several heated minutes.”

“It was no more than a ploy on Gaylord Perry’s part to try and throw us off balance,” Wills said. The manager repeated his home plate protest at the start of the second and third innings as well. It all seems like a man jumping at shadows, except that Perry said this in fact was his plan along:

“I wanted to give them something else to think about,” Perry said. “I wanted them to protest.” He watched Wills fume and “loved every minute of it.” “I knew it was legal. The rule book says as long as it’s uniform2 in color and is not white or gray, it’s okay.” He had even confirmed this with the umpire before the game started.

“He sure didn’t have that glove in the Kingdome,” earlier in the season, Wills said. Seattle’s manager said his protest was not strictly about the color. The “new” glove appeared “pretty well worked,” and Wills believed it had been dyed. “It was dyed red. There aren’t any red cows.”

“I ordered it about a month ago,” Perry said. “I just said I wanted a big red one.” It wasn’t his fault he’d been traded in the interim. And he was ever the creative optimist. When life gives you lemons, make psychological distractions.

Perry had confirmed the red glove was another PsyOp, but this one was just so ridiculous. Surely the Mariners’ players couldn’t be rattled like a group of unfortunate bulls in some plaza de toros?

“He didn’t get us out with that red glove,” said Seattle right fielder Tom Paciorek. “He got us out with his forkball, his slider, and real good off-speed stuff.” At last, a grown-up.

Paciorek was right, of course. Perry’s pitching talent was real and—it seemed—everlasting. The rest was just a sideshow…wasn’t it?

That night—playing under protest over Perry’s glove color—the Mariners committed three errors and allowed two passed balls that led to New York runs. Meanwhile, Perry went seven innings, yielding eight hits and two runs. It was his 600th career start.

At 41, what little remained of Perry’s hair was nearly gray. “Here you are, an old dog learning new tricks,” one admiring reporter said after the game. The pitcher laughed. “Old dog? Why call me old? Just call me a dog.”

Or, evidently, a matador.

Comments leading Project 3.18 to a fun story are always welcome, folks! Keep ‘em coming, and thanks again, Matt.

The Part Where We Do the Retrospective

Speaking of hype-men for shady characters, we have (belatedly) picked up on what seems to be a Substack tradition of highlighting some of one’s most popular pieces at the end of the year. We get the concept, but showering already-well-received stories with even more attention seems like making the rich even richer.

Instead, we thought we’d highlight a few great stories that weren’t as popular—in the first year of a newsletter, that can happen!

So, if you’ve been with us the whole way, you are awesome and we love you, and you can stop here. But if you’re newer and looking for a few more good stories to read next to the beach or the space heater, here are three lesser-known darlings from 2024:

We wanted a bravura opener for Project 3.18 and, taking advantage of our unlimited lead time, we crafted an opus of the 1960s New York Mets, from their tragicomic beginnings, the cracked adulation of the earliest Mets fans, to their triumphant 1969 World Series victory, an event that sparked one of the greatest fan-rush events of baseball’s postwar era. Part 2 includes what remains our favorite visual gag to date—and you know how much we appreciate visual gags around here.

It was supposed to be just a little forfeit piece, but a throwaway mention of something called the “work-or-fight” order sent us spiraling into the saga of baseball’s most perilous moment, when World War I and several cold-blooded Washington bureaucrats nearly shut down a national sporting institution. We did get to the forfeit, eventually. This one dropped at the height of summer, but we think it may have a second act here in the doldrums of January.

Another early one, our first forfeit story, the moment we realized a simple story of baseball hijinks often hides a killer historical subplot. For this one, it was the role of the municipal police in a modernizing New York City in 1907, and the ramrod commissioner who wasn’t above creating a little chaos in the service of getting his way.

Now that we’ve cleared off 2024’s old business, we’re ready to start in on the new stuff. And by “new,” we of course mean 40 years old. We’re off to 1984, where we’ll find an ejection story that has both quantity and quality.

On January 13: “Lucky Thirteen”

National Lifeguard Appreciation Day is July 31, and you better believe we’ll be bringing Billy Earle’s story back for an encore.

The glove color rule used the adjective version of “uniform,” meaning “all of one,” or “all the same.” The rule did not require that a glove’s color be aligned to other aspects of the team’s livery; the only restriction was that gray and white were prohibited. In other words, Perry could have pitched for the Yankees using a hot pink glove and it would have been permitted, as long as it was entirely hot pink.

Today they can toss a glove if the lacing is too long… color too I’ve heard. Rulings change. Fingers to the mouth used to be a No No. Today it’s common.

But I must say about catchers framing the ball; why is it legal? To me it’s cheating. WHY?

Baseball needs more guys like Gaylord Perry - always entertaining.