Pink Tea at the Polo Grounds - Part 2 of 2

In which New York’s police commissioner hugs the stove too hard and “the tools of ignorance” get a little bit smarter.

And now, the conclusion. We’re going to start with a little biographical sketch here, so you have a good sense of the man who was willing to leave 20,000 people, two baseball teams, and one poor umpire unprotected in the cause of improving public safety.

In case you need it, here’s Part 1.

A few months before Opening Day in 1907, Brigadier General Theodore Bingham, New York’s second-year Commissioner of Police, duly submitted his annual report to the city. This was newsworthy, as it was “the first time in the history of the department” that the report had arrived on time. Classic Bingham.

An outsider, who had no connections to the department’s patronage networks or the Tammany political machine that dominated New York City politics, Bingham received a mandate to push or pull the city’s police force into the twentieth century—by any means necessary. So empowered, Bingham set about his work with a the zeal of a crusader.

“If I can stay honest,” in the job, he promised, “I’ll raise hell.” He proceeded to do precisely that.

Bingham’s January report called for 2,000 additional patrolmen, against a budget that allowed just 600 new hires, showing how little he cared for the department’s previous status quo. He also began advocating for sweeping changes in the force’s detective bureau, which was widely perceived as rife with corruption.

The commissioner requested more clerical workers, to relieve trained officers from such work and return them to the streets, and asked the city for “relief from the duty incident to work upon elections.” From there, it was just a short walk to the position he had taken by April 1907: NYPD officers should also be relieved from the duty to work large-scale private events, including baseball games.

Either because they liked his ideas or because they wanted him to stop writing them so many angry letters, many of the state’s major politicians supported Bingham’s reforms. In fact, on April 11, the very same day as the game, the city held a public hearing on the details of the “Bingham Police Reform” legislation about to be signed into law.

The bill gave Bingham power to elevate and demote officers to and from detective roles at any time, and many in the 245-member corps understood their days were numbered: the commissioner had publicly stated that he believed “only twenty or thirty were worth keeping,” the rest being “incompetent and corrupt.”

Bingham also put an organizational structure in place that large police forces continue to rely on in present day–the “squad” system, and he also added specialized roles within each district, with point persons for “the commercial swindlers, the pickpockets, and the pawnshops,” and making possible what would become a huge portion of television producer Dick Wolf’s creative output1 a century later.

On the eve of achieving his desired reforms, Bingham decided it was at last time to enact his plans to remove the police from activities and spaces where he felt they had no proper place. As was his custom, the commissioner just ripped the band-aid right off, prohibiting his men from working Opening Day at the Polo Grounds.

As thousands in the stands demanded the game proceed despite the crowd milling about in the outfield, someone in authority (our vote is Coogan) finally made their way outside the park, seeking police officers who could help. Several roundsmen (some of the last officers to ever work in that capacity–the Bingham Bill converted them to “sergeants,” a more recognizable term) were flagged down and made aware of the deteriorating situation within the Polo Grounds. Their response was grudging and hardly proportionate:

“The Roundsman in charge (a man named McLoughlin) sent in an imposing2 force of four men and marched them to the front of the grandstand, but refused to take further action.”

The crowd was unmoved by the police’s limited demonstration, so the officers picked two men out of the mob of cushion-throwers and arrested them, “without any protest from their fellows, nor any cessation of the cushion-throwing and general disorder.” Joseph Biggs, 21, from the Bronx, and William Miller, 23, from Newark, were charged with disorderly conduct but were guilty of little other than possession of bad luck.

The four police were ultimately “unable to do anything with the unruly mob, some of the members of which amused themselves by throwing bottles, glasses, and cushions in all directions.”

Surveying the scene, Roundsman McLoughlin chatted with Giants’ catcher Roger Bresnahan and remarked that he had orders not to interfere with the crowd, even if he wanted to. Fortunately, according to the wire service report, from that point on, the demonstration turned into “a good-natured jollification.”

Bill Klem had no use for jollification of any nature, particularly during a ballgame. New York’s fifteen minutes came and went, and the umpire declared the game over and forfeited to the Phillies.

The Giants did not protest the decision, which only overwrote what was otherwise a shutout loss. The players and the fans—in the stands and on the field—presumably found their way out as Roundsman McLoughlin and his colleagues “supervised.”

Immediately following the game, no one representing the Giants could be found to make a statement. McGraw was safely clear of this one, team owner and president John T. Brush had been absent from the field all day, and club secretary Fred Knowles shut himself up in the park’s business office and refused requests to be seen. “Those who gained access to the office saw Knowles busily writing at his desk and maintaining a ‘Sphinx-like’ silence when queries were addressed to him.”

The next day brought broadsides of scorn from the New York press, aimed at any and all connected to the game, which had devolved into a “howling farce,” one writer declared. Another said the forfeit was “the most disgraceful scene ever witnessed in New York and will forever remain a blot of shame on the sport loving people of the city.”

The New York Sun newspaper was at the center of the day’s pile-on. Their editorial linked the fans’ behavior to McGraw’s modus operandi. “The Polo Grounds public has been educated to expect disorder and a small part of it has actually been trained to create it or help it along.” Without their master, the Sun felt, McGraw’s dogs had slipped the leash and run amok.

Outside of the city, where the Giants and their manager were significantly less popular, some papers were downright unethical in making a similar point: “CROWD FOLLOWS M’GRAW’S TACTICS,” a headline in Indianapolis blared, “OVERRUNS GROUNDS AND GAME IS FORFEITED.” The subsequent report didn’t get around to mentioning that John McGraw hadn’t even been present.

Such was McGraw’s notoriety that Commissioner Bingham, who essentially caused the whole debacle, came in for softer criticism than the absent manager.

“The Giants had been given sufficient notice from General Bingham,” the Sun proclaimed, a rather generous choice of adjective given the circumstances. If the commissioner had in fact only given notice that morning that the police would be unavailable, he had, at best, put the Giants in a difficult situation and contributed to the ensuing chaos.

The Sun did at least nod at Bingham’s responsibility (while taking another slap at Giants fans): “Commissioner Bingham might have taken into consideration the record which the Giants have made in recent years for playing baseball with their mouths and fists and the general incitement to riot which they have furnished the small hoodlum element in the large multitude of patrons of the national game.”

Despite being the hometown paper of the rival Superbas (who would not dodge their first trolley until 1911), the Brooklyn Daily Eagle poured cold water on what it felt were many overheated accounts of what had taken place at the Polo Grounds. The Daily Eagle described the day’s events as nothing more than “a pink tea musicale, where during an intermission the crowd gathers around the performer, some gazing at him enraptured while others talk to him about his talents.”

“The only riot,” the Brooklyn paper assured its readers, “was that of the colors used in telling about this incident.”

For once, the umpire was held blameless. This was already Bill Klem’s second forfeit, and while he’d been a controversial figure in the first, this time, all accounts agreed that the umpire had acted reasonably and by the book.

Forfeiture, one paper explained, was “the National League’s only protection against danger.” The league also had rules (Rule 77, in 1907) requiring the home club to provide police protection for players and officials, something the Giants had failed to do. That was intolerable, the writer warned. “In a close contest with ill-feeling between the teams, there might easily be disastrous consequences.”

The following day, club secretary Knowles had apparently finished catching up on his correspondence and was willing to talk, after a rain delay inconveniently freed up his schedule.

The secretary announced that the club would hire 60 men from the Pinkerton Agency (a private company that provided contracted police and security services, as well as the occasional strike-break) to preserve order on the grounds for the remainder of the season. “We don’t want any more scenes such as that of yesterday, and we have taken the necessary precautions to prevent a recurrence of them,” Knowles assured the press. As to what had led the club to proceed on April 11 without police or Pinkertons on hand, Knowles did not say, nor is it clear he was even asked.

Knowles unveiled one other step, and it was a classic from the bargain-bin of half-measures baseball has often found so tempting: the club would stretch a four-foot-high strip of chicken wire out in front of the outfield rope, in order to deter any standing behind it from entering the field of play.

All the extra resources ended up wasted because one spectator, the aforementioned “weather man,” had seen quite enough. The persistent, swollen clouds opened once again and this time it was rain that came down. “The Polo Grounds looked like a lake and the Giants were compelled to hug the stoves to escape an attack of clattering tooth,” went one delightful account. The deluge washed out not only the Giants/Phillies in New York, but six of the seven other major league contests scheduled that day.

Faced with a downpour, Secretary Knowles acted on behalf of the absent field manager and postponed the game. This came as little surprise, even to the few hundred hardy fans who had made their way to the Polo Grounds to huddle under shelter until their rain checks (a new innovation at the stadium that season) could be punched.

It was a fitting start to what would turn out to be one of John McGraw’s least impressive seasons in full control of the Giants. In 1907, his club would finish in fourth place, still in what was regarded as the “first division” of top-half teams, but a dismal failure by the manager’s standards and those he’d instilled in New Yorkers. McGraw blamed himself…for letting the club get too old on him. He cleaned house that off-season and in 1908 his re-tooled Giants battled the Chicago Cubs in one of the most thrilling pennant races of the young century and perhaps ever.

And while an iron will and a combative spirit would make John McGraw one of the most successful managers baseball has ever seen, the same traits proved less effective in the world of police administration. More savvy leaders might have taken a lighter hand to their work after the success of the Bingham Bill, but then again, such a compromising person might not have gotten as far in the first place. In 1908, the commissioner pushed, unsuccessfully, for immunity from political oversight and made headlines by publicly wishing that the police captains who’d resisted his attempts to force them out would solve the problem by dying.

In 1909, he called New York “the dirtiest place on this earthly footstool” and vowed to continue his quest to reform and clean out the police department, despite, he declared, being offered bribes to slow down on certain aspects of his work. His enemies within the city’s still-powerful Tammany Hall political organization were gathering, and that year, Bingham handed them the trump card, when he included an un-convicted 19-year-old in a “Rogue’s Gallery” of public photographs, a shame that had previously been reserved for only those found guilty of their crimes, causing a scandal.

The mayor tried to save him, ordering administrative changes beneath Bingham and removing several of his staff. The commissioner flatly refused to cooperate, and within a day he himself was sacked. He later made some careful noise about running for mayor himself, but ultimately settled for being an anti-Tammany public speaker.

Bingham’s zealotry and unwillingness to compromise (combined with the sphinx-like frugality of the Giants) left the Polo Grounds unprotected on April 11, 1907. Hell was certainly raised as a result of that decision, an unmistakable signal to all private entities who had hitherto taken advantage of free police protection. By allowing Opening Day to run to riot, the commissioner showed was not bluffing: the NYPD moonlight buffet was now closed, and its patrons had best make other plans.

Now that’s what I call a forfeit.

One Other Thing

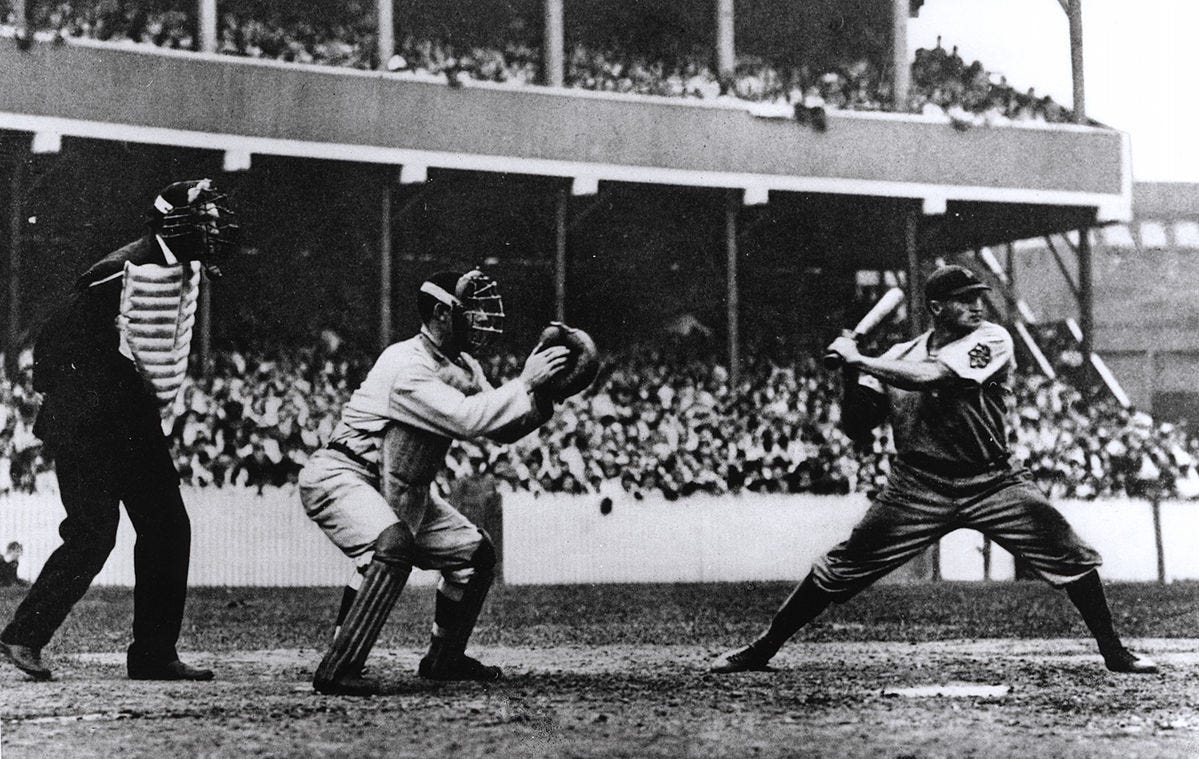

April 11, 1907 was notable for another reason. Amidst the otherwise-dispiriting early innings, the Giants’ catcher, Roger Bresnahan, caused considerable amusement by wearing long shin guards similar to those worn by cricket players.

Several Negro League players had experimented with similar equipment as early as 1905, but this day marked its debut in Major League baseball. It was a moment worthy of lighthearted commemoration in the newspapers: “As he displayed himself, togged in mask, protector, and guards, [Bresnahan] presented no vulnerable surface for a wild ball to strike.”

This would not be Bresnahan’s only “ah ha” moment with catching equipment: he would also introduce the padded face mask.

Some accounts place blame for the day’s forfeiture on Bresnahan’s shin guards, claiming the absurdity of his appearance inspired salvos of snowballs from the crowd, but we have found no contemporary account which reflects this. What we have seen suggests the opposite:

“The white shields were rather picturesque in spite of their clumsiness, and the spectators rather fancied the innovation, howling with delight when a foul tip in the fifth inning rapped the protectors sharply.”

Glossary of Old-Timeyness:

“Pink Tea”: a decorous or ineffectual affair or proceeding

“Jollification”: Merrymaking, festivities

“Togged”: to be dressed in

Thank you for reading this tale from the Roosevelt administration (Theodore, not Franklin). We will dig deep into the past every few months or so and we hope you’ll come for the riots and stay for the new vocabulary and some quip-rich history.

We would watch the heck out of a Law and Order: Pawnshops series set in 1907.

There is a great deal of ironic sarcasm in Gilded Age newspapers.

For anyone interested in reading more about this era, I highly recommend "The Celebrant" by Eric Greenberg.

While it is a work of fiction, the players, managers, owners, and league officials are historical figures, and the games described were played on the dates given, and line scores, batting orders, and the standings of the clubs are accurately reproduced. Very few liberties have been taken with the play-by-play, and none at all where World Series games are concerned.