On the Lines

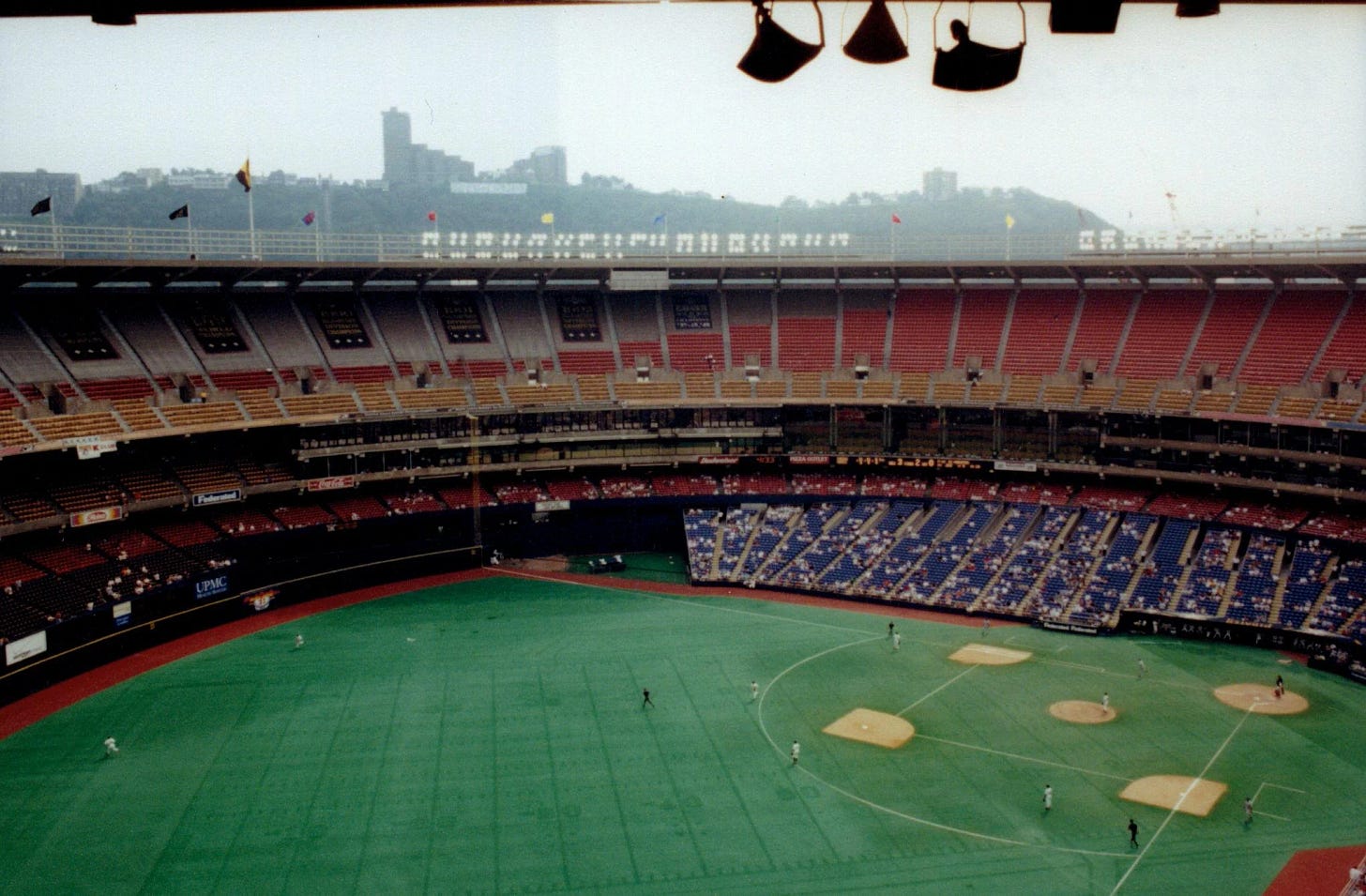

In 1975, eight women donned infield gloves and took the field at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh.

Way back in April, as we carefully constructed a Venn diagram of baseball and a nationwide hot pants craze, we came upon a related phenomenon: the “sweeper.” Our introduction came by way of Johnny Bench, who performed a good-natured impersonation of Atlanta’s “Susie the Sweeper” in 1972, during a softball game between the Atlanta Braves players and their wives.

After discovering “Susie,” we started looking for more examples of women hired to work on the field for purposes of spectacle. This search led us to Pittsburgh, of all places, and a group of women who did the sweeping, yes, but a lot more as well.

The thirty years following the 1954 dissolution of the All-American Girls Baseball League was a historically barren time for women who wanted to work in major league baseball. There were no national-level professional leagues for women, and few options for big-league employment that even came with a view of the field.

In Pittsburgh, for example, 1974 was the first year where women were hired as ushers at Three Rivers Stadium, and this was such a break with tradition that it was covered in the newspapers. In a world where female ushers were news, the baseball pickings for women were slim indeed. If the 1940s and 1950s were the Classical Period of women’s baseball, the 1970s were deep in the Dark Age.

A sliver of light appeared in 1975. That year, the Pittsburgh Pirates decided to “liven up” the foul lines of their featureless stadium with an all-female crew of performers/foul-ball-chasers. In this era, no chance for a cutesy, punny nickname was spared in women’s sports, and so the Pittsburgh ball girls were naturally dubbed the “Pirettes.”

The wordplay was solid, but totally unnecessary. While some team nicknames presented awkward gender conflicts (Cowboys, Rams, etc.), there have been some terrific women pirates, as good at pillage and murder as anyone. But Pittburgh’s female pirates got the diminutive -ette suffix, lest anyone miss that this was a gender-based stunt.

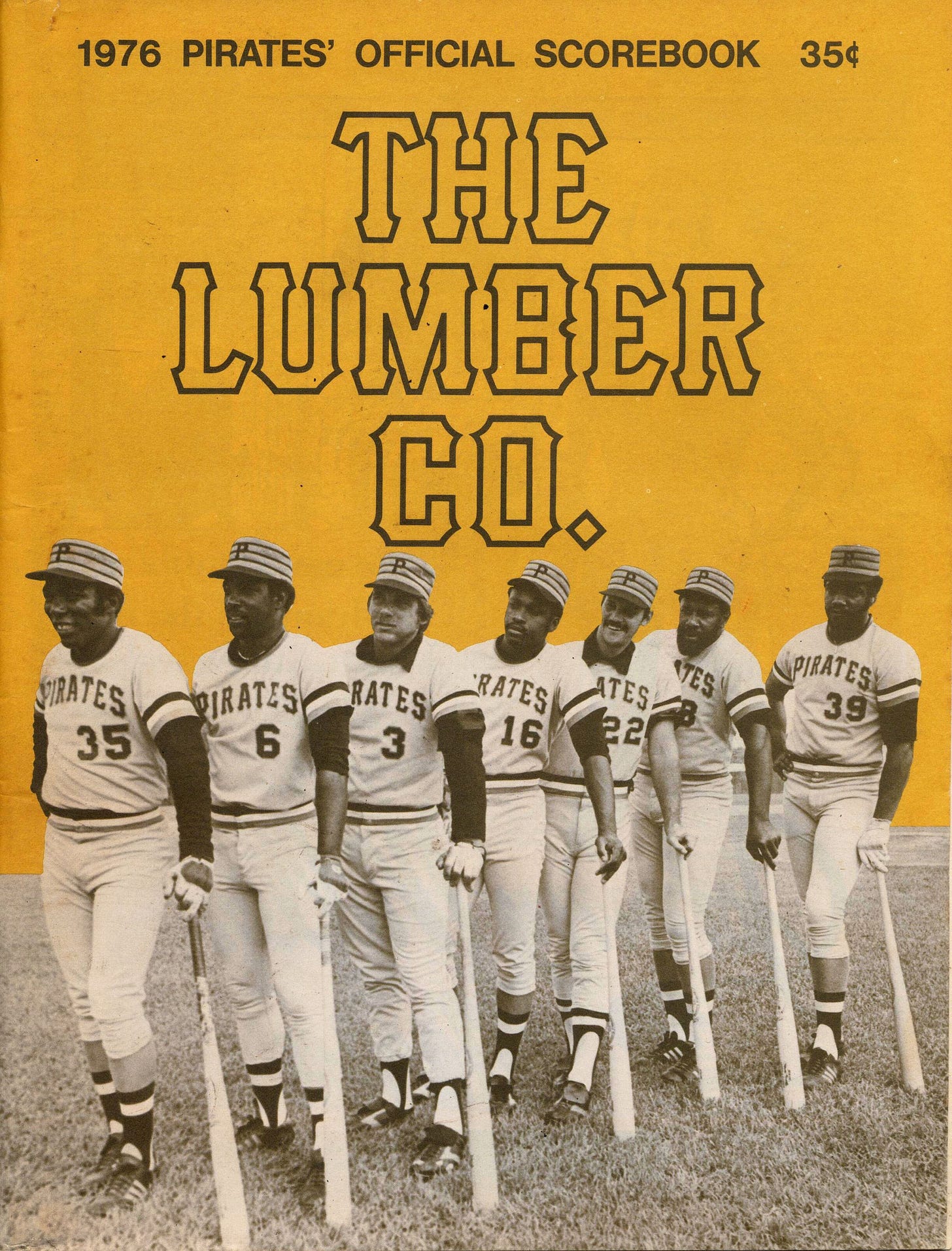

The Pirettes’ creation-tale doesn’t really do their legacy any favors. According to a July 1975 article mentioning their incorporation, the Pirettes were among a suite of new, fan-friendly ballpark “innovations” aimed to punch up lackluster attendance. You see, there were concerns that the Pirates’ lineup of predominantly-Black players was depressing ticket sales.

This sentiment was voiced even by some of the more outspoken Pirates themselves, including pitcher Dock Ellis, who said it flat-out that summer: “The reason the people are staying away is because there are too many black dudes on this club.” Lots to unpack there, but long story short, the team hoped the prospect of an all-women foul-ball crew might help overcome any lingering race-based discomfort some fans might be experiencing.

It’s possible they debuted in the spring—coverage of the Pirettes was neither close nor consistent—but by June they had unquestionably arrived, announced as part of the fun in a jam-packed weekend featuring two doubleheaders, a car giveaway, appearances by Pirate Pete (the team mascot at the time) a softball game between the wives of Pirates players and the wives of Pittsburgh Steelers football players, and… “the Pirettes.”

There were eight of them that first season, six regulars and two “alternates,” chosen from among 237 applicants and 30 finalists, on the basis of “poise, personality, looks, and ability in baseball,” probably in that order.

Denise “Denny” Ellis was 18, a recent high school graduate who went out as homecoming queen and the reigning West View Chamber of Commerce Christmas Holiday Queen. Ellis had also done professional modeling work since she was 15. Ruth Blasko, 19, was another member of the first class. Blasko was a sophomore at nearby Indiana University of Pittsburgh, majoring in math, though she would soon switch to business.

Ellis said she came to Pirates games regularly as a spectator, but had no team sports experience to speak of. Still, as an aspiring professional model and Pirates fan, this was the perfect summer job, and she went for it.

Blasko came from a big baseball family. Her father coached an American Legion team and her brother was captain of the high school squad, but she had little experience with the game herself (the Pirettes auditions were the first time she set foot in Three Rivers Stadium). Blasko’s father saw the Pirates’ ad for ball girls in a newspaper and encouraged her to apply. She did, mostly as a lark. “What the heck, right?” She was thinking about becoming an airline stewardess and thought the “people” experience would be helpful.

The audition process began with a group interview. Members of the Pirates’ public relations staff sat down with a group of applicants and asked a few questions. It was clear that some of the applicants had not expected a quiz, including Blasko. “They asked me what place the Pirates were in and I said, ‘Oh, they’re up there somewhere.’ It turned out they were half a game out of first place.” Close enough, apparently.

The Pirettes’ primary duty would be to field ground balls that went foul up the first and third base lines, so the semi-finalists were sent to a fielding showcase of sorts. The applicants met their first Pirates players at this stage: reserve catcher Duffy Dyer and pitcher Larry Demery threw them three ground balls each. The fielding tryouts were exuberant and chaotic. At one point Denny Ellis somehow got turned around and took a ball thrown by Demery in between her shoulder blades.

Blasko described a pageant-like atmosphere, not something she was familiar with, but one that was definitely appropriate to what the first Pirettes were expected to be. “They lined us all up and looked at us. I felt like I was at an auction, [being] bid upon,” she laughed. Blasko, Ellis, and six others were selected. Some of them didn’t even own baseball gloves.

The first Pirettes uniforms were done on the cheap. The only glaringly-misplaced feature was a chunky belt with large grommets, but at least they weren’t sent out in heeled boots. Each girl wore a yellow t-shirt with black block lettering announcing her as a member of the “PIRETTES;” a black headscarf worn mainly wrapped around the neck as an accessory but occasionally unfurled in order to wave at the crowd; white shorts (short, but not short-short, if that makes sense); yellow tube socks with black striping; and white tennis shoes. No hats, or helmets, lest someone fail to notice that these were women and be deprived of the resulting amusement.

Whatever the women had thought they were getting into, it became quickly apparent that their baseball skills were under a microscope.

“When a ball comes toward me,” Blasko said, “I’ll be honest, I do get a bit nervous, because the crowd watches us. We have to watch the balls closely. If we interfere with a fair ball they’d probably get really mad at us.”

Ellis had the same experience. Fans didn’t cheer for “poise.” “If we catch the balls, the crowd yells for us; if we miss them they boo—they treat us the same way as the players.”

For their part, the players pitched in to bring the women up to level. They included the Pirettes working each game in their pre-game warm-ups, setting up fielding drills: “They bunt the balls to us because they say we need the practice as much as they do.”

Larry Demery— trying to make up for hitting Denny Ellis during her audition—brought her a pack of gum every time she worked. One of the Pirates’ coaches, Jose Pagan, loaned his glove to one of aspirants who didn’t own one, and when she made the squad, the arrangement stuck.

The Pirettes’ other responsibilities included greeting the visiting players, being available to sign autographs, and a fifth-inning sweeping routine. In Pittsburgh’s version, each Pirette would take their standard-issue short broom and brush off first and third base before converging on second base and the second base umpire. The sweepers would dust off his shoes and then give the official a kiss on the cheek and/or a playful swat on the rear.

Ellis said the umpire received a kiss or a smack based on whether he was doing a good job, and we wonder who made that assessment and how.

This performance was standard sweeper stuff at the time. “The fans really enjoyed it,” Blasko said, though described this ritual as the part of the job where she “felt funny.” It’s not clear if she meant funny-“ha ha” or funny-“my summer job requires me to kiss a strange man old enough to be my grandfather,” but we’re going to go out on a limb to say this part wasn’t her favorite.

The pay was $10 per game, but an individual’s take diminished quickly once the 81 home games were split between three crews. Still, the job came with—as Ellis put it—lots of “fringe benefits.”

Access to famous baseball players was certainly one of those. Blasko singled out third baseman Richie Hebner as a favorite. “He’s a riot.” Of course, the Pirettes mostly spoke of the players, coaches, and umpires in platitudes. Everyone was “nice,” “real nice,” or, as Ellis prophetically said, “they are all so put-together and sincere, like one big, happy family.”

Blasko said that Willie Stargell and Ken Brett enjoyed joking around with the girls, and she shared an anecdotal example she seems to have found amusing. “Part of our uniform was these white tennis shoes which we had to keep very clean, and the players kept spitting tobacco on them.” … We think you had to be there.

By October, Blasko said she had gotten to know most of the Pirates well, and also met people in radio, tv, and local business. She helped host the opening of a new mall. The evening ended in a formal dinner with speeches, creating the one time Blasko felt self-conscious in her uniform. “Everybody was dressed up and we had to wear our uniforms–shorts and t-shirt.”

All in all, she gave the job a vote of confidence. “I would recommend the job for any girl. It’s fun, the pay’s not bad, and the entire experience is memorable. It’s an experience that most people never get.”

The Pirettes were back in 1976. Someone had realized having three crews idle each game was wasteful and the corps was whittled down from eight to five. New auditions were held, but some of the press-friendly stalwarts from 1975 were invited back.

Denny Ellis had started as one of the least athletic among the group, but she’d put in the work and was name-dropped in post-game accounts several times: “Ellis gloved a scorching foul grounder outside the first base line like a veteran shortstop, off Willie Stargell’s bat,” earning a hearty, approving cheer.

Wearing the Pirates’ striped “pill-box”-style cap (a league-wide nod to the American Bicentennial celebrations that Pittsburgh would hang onto for several years), Ellis also starred in advertisements for her alumnus, the Powers Career School (programs in Interior Design, Fashion, Reception, Stenography, Finishing, and Modeling): “Let Powers go to bat for you.”

The calendar quickly flipped to 1977. The squad got even smaller, composed of just three rotating members, all holdovers from 1976, including Blasko, Ellis, and Michele “Mickey” Dias.

In July 1977, the Pirettes got their first big write-up in two years, and we had high hopes for this coverage, because it was provided by Mary Sedor, whose credentials included being a woman herself and a sports writer for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Ruth Blasko was finishing college, now widely regarded by her friends and acquaintances as a baseball expert. She had come to feel at home out on the Tartan Turf at Three Rivers. “I used to be so nervous about the ground balls. Now, after three years, I’m not nervous at all.”

It was a long way from where she’d started. “Pretty ironic,” she said, thinking about her audition in 1975. “They asked me, ‘What place are the Pirates in currently?’ I didn’t know. My dad is a diehard Pirate fan and he took me down to the tryout. He almost had a bird1 when I told him my answer. They asked, ‘What’s your favorite player?’ I didn’t even know any players’ names, so I said, ‘They’re all my favorite.’”

“I still think they’re all great,” she said, but now she could name most of them, and she had a few to single out. “I think Dave Parker’s a really fantastic player. Rennie Stennett is, too.”

Nearing the twilight of their Pirette careers, occasional bruises had brought a taste of the real world. “The balls come pretty fast and hard sometimes,” Blasko said. She recalled attempting to field a ball that took a bad hop and “clobbered her in the head.” One of the Pirates, Bill Robinson, fetched smelling salts, but Blasko refused to leave her post.

Mary Sedor had written a solid piece, giving Ellis and Blasko an opportunity to reflect on the job and how they had grown as a result of their experiences. Sedor had nearly made it to the end without using “petite,” “pert,” “winsome,” or “fetching”—a first for coverage of the Pirettes. She concluded with Denny Ellis, who was now 20 and expecting to be swept into retirement, though not without protest: “I’d love to do this for the rest of my life. I’d be down there even as a senior citizen in a wheelchair.”

It was a lovely sentiment to end on, evoking the enthusiasm of youth, the inevitable passage of time, and the ageless pleasure of baseball. Well done, Ms. Sedor, go ahead and close us out:

But she may have to settle for dinner with hubby.

Mary! You were so close…

As Ellis had expected, the Pirettes embraced a “youth movement” in 1978, bringing in an entirely new crew of mostly high-school-aged talent. And while their predecessors had debuted only three years prior as “eye-pleasing foul-line adornments,” the new Pirettes benefited from the seriousness with which the first class had approached their work. Athletic talent from the Pirettes was now expected and acknowledged.

Much was made of the new Pirettes’ sporting backgrounds–in softball, basketball, track, and cheerleading. In one promotional shot, they were shown wearing jeans, caught in the act of throwing a baseball, as if to establish right away that they all knew how to do that.

The whole “sweeper” routine was abandoned that year. The Pirettes could triumphantly put away their brooms…and pick up their dishware, for a revised procedure that saw the ball girls bring all four umpires “drinks and some pleasant conversation” during the fifth inning. It wasn’t much progress, but it was some.

And there was discourse, actual discourse! Introducing the new class, a cynical sportswriter described the idea of the Pirettes as “another attempt at gate hype, male chauvinist diversion.” But he saw something he recognized and respected in the sporting pedigree of the incoming squad. One of the recruits, Terry Williams—captain of her high school softball and basketball teams—even confronted the quiet part out loud: “I’m used to being on a field in front of people,” she said, “and I’ve never thought of myself as a sex object.”

Baseball was changing, too. Free agency had arrived, making some of the nice guys in the dugout into millionaires. It remained to be seen if money would destroy the sport, but new Pirette Barb Colaizzi said the early returns were hopeful:

“[The players] have been so nice to me, which was a real surprise. You’d think they would be really uptight making so much money and having a lot of pressure on them. But they’re not anything like that.”

The Pirettes, however, still made $10 per game.

Further change came in 1979 when the team’s new vice president of public relations and promotion, Jack Schrom2, introduced the greatest Pirette innovation since the advent of jeans. For the first time, the women were empowered—encouraged, even—to give their foul balls to the fans. “When you see a businessman in a three-piece suit dive over a chair for a baseball, you know that’s important,” Schrom said.

Drawing down the Pirettes’ ball hoard was a great idea, fan-friendly and kid-friendly. Little kids, unable to compete with the big kids (i.e. grown adults in three-piece suits) when foul balls were hit directly into the stands, would line up in the aisles near their closest Pirette and wait their turn to get a ball. It was all so wholesome. And it was a huge success. Attendance at Pirates games rose by nearly 500,000 in 1979, passing 1.4 million fans.

Oh, and the “We are Family” Pirates won the World Series that year. That may have goosed attendance a little, too.

The Pirettes lasted until 1986, but their final seven years saw decreasing interest in the brand as women pushed further into both sports and the workforce in general and made gendered stunt-casting look more and more archaic.

Caught up in a major ownership transition and a bad team in the mid 1980s, the Pirates were in such financial trouble that they canceled the Pirettes program in 1985, ostensibly in order to save costs on all the baseballs being given away. Such a ridiculous statement accordingly made national headlines and the group was reestablished in 1986 to save some face, but stripped of its power to create souvenirs for kids. In 1987, no auditions were held and the “Pirettes” gimmick was quietly dropped, but women have remained a part of Pittsburgh’s foul-ball crews ever since.

Progress isn't always a rocket with a lone astronaut strapped inside. Sometimes it's a hundred different bits and pieces of determination and diligence, piling up under our feet until we've been raised just high enough to see things differently.

The Pirettes didn’t transform anything, or solve any big-ticket problems. But in a dark age for women in baseball, they brought what light they could. They got access via a promotional stunt, but they took the chance they had and took it seriously, whittling away at the gimmick with dignity and hard work until there was nothing remarkable about women on the foul lines…except the the plays they made:

Best in the business, indeed.

Speaking of big tickets…the Women’s Pro Baseball League hopes to begin playing in 2026, with six teams in the Northeast United States and a goal of reestablishing a culture of professional women’s baseball on a level not seen since the 1950s. Mark your calendar.

Next week we’re going to cover our fourth forfeited game—fifth, if you count Ten Cent Beer Night. As we’re nearing the holidays, we’ll take it easy on you, without mixing in a global war. But our story takes place in 1937, so we reserve the right to mention the New Deal at least once, if necessary.

On December 9: “Hurry Up and Wait”

“To be shocked or agitated.” Let’s bring this back.

Another Schrom innovation was displaying the players’ names on the backs of their uniforms. The Pirates were apparently reluctant to do this for fear it would cut into scorecard sales!

A whopping $10/game! How did the Pirates manage to squeeze that from their profits?

Living in Pittsburgh, but not attending a Pirates game in several years, I don’t know what the fielding crew situation there is these days. Also, thanks for the shoutout to my current employer, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.