Never Late for Supper - Part 1

In the early years of his career, Dick Allen quickly made a name for himself, but the world had other ideas.

When I was in college, I had a job as a shipping clerk, processing packages for one of the university’s engineering buildings. UPS handled the bulk of our traffic, and the regular driver on our route was a friendly central Illinois sparkplug named Jeff (I think it was Jeff). Wearing the iconic brown shirt and shorts in weather fair and foul, Jeff talked fast, walked fast, and never quite came to a full stop.

Jeff would drive up, hop out, and we’d do a solid 35-38 seconds of chit-chat while he unloaded and I signed. I appreciated that he talked to me at all, since he was a functioning adult in his 30s and I was 18 years old and evidently didn’t know that you could buy fitted clothing. Our conversations ran the whole gamut: sports, weather, and upcoming weather. We bonded.

Except, early in our acquaintance, Jeff accidentally called me “Phil.”

The first time it happened, I wasn’t sure I’d heard him right. A week or two went by before I heard it again, and, well, maybe I still wasn’t sure, so another month went by and then I had no choice but to conclude, yes, he was calling me Phil. By then it had been several months, and I found myself too embarrassed to correct him. I could think of only one workable solution—I would become Phil.

“Hey, Phil, how about those Bears?” “How you doing today, Phil; how was your weekend, Phil?” I stopped registering the difference. All was going according to plan, and eventually I’d graduate and move out of town, at which point Jeff and Phil could bid each other a warm, uncomplicated farewell. Years went by.

My shifts were scheduled such that when I was on duty, my manager was off, but otherwise he was on the dock, and he and Jeff knew each other well. One day during my senior year my manager was on-site with me when the UPS truck rumbled in. I was immediately uncomfortable. Jeff bade me a typically warm greeting and mentioned that it was raining. My manager’s head snapped around.

“Why’d you call him ‘Phil’? That’s not his name.”

Jeff froze. He looked at me for help. Phil, his eyes asked, what’s going on here?

I don’t remember how I explained myself, but I know I did most of the apologizing and that felt right. I’d dragged poor Jeff into this mess with me. He looked so crestfallen. My manager laughed all the way into his third cigarette break of the morning.

Our rapport was never the same after that. Jeff got along great with Phil; Phil was a cool dude who knew his sports and his upcoming weather. Paul was a kid so anxious he had let another person call him by the wrong name in a professional setting for the better part of three years. Jeff really didn’t know how to talk to someone like that.

“Hey Paul,” he’d say, enunciating carefully (and unloading as fast as he could). Hearing Jeff say that name made me wince.

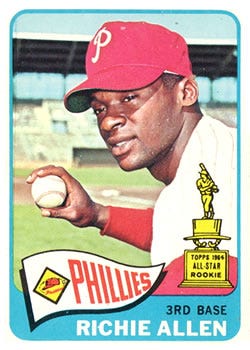

When he arrived in the major leagues in 1964, a touted Phillies rookie named Richard Anthony Allen gave an introductory interview for a reporter writing for the Associated Press. The story covered his roots in a small town in western Pennsylvania, Wampum, and didn’t linger on Allen’s time in the minor leagues, particularly the year he’d just spent for the Phillies’ AAA affiliate club, the Arkansas Travelers, based in Little Rock.

That assignment shoved him onto the front lines of the ongoing battle for racial equity in the United States. In a state where many were still actively fighting integration, Allen became the first Black player to ever play for the Travelers. The Phillies did nothing to prepare Allen for this fraught assignment, nor did they try to clear a road for him—no one in Little Rock knew the Phillies planned to integrate their team until Allen showed up. The Travelers’ manager, Frank Lucchesi, did little to protect Allen or stand up for him as an equal member of the team. He was on his own1.

In Little Rock he experienced prejudice and segregation like nothing his life to that point had prepared him for, and as an (unwitting) symbol of integration he was subject to pointed shows of bigotry and full-blown hatred. Not even the ballpark was safe. There were protests, demonstrations, and some of the signs waving at him from the stands bristled with hate speech. Not only was he unwelcome, his presence was something people felt they had to actively resist.

At first he lived and played scared, until he figured out how to play angry. “I never wanted to be a crusader,” he remembered later, but in that situation, the only other choice was to feel the way the people waving the signs wanted him to feel. So he got angry.

Allen clubbed 33 home runs and drove in 97 runs that season, league-leading numbers. He successfully slugged his way out of the minors, but the experience had changed him. From that day on, he wrote in his 1989 autobiography, Crash, “I decided if there was ever a double-standard again, I would be the beneficiary, and not the other way around.”

After making the Phillies in 1964, Allen told reporters he was eager to leave the “unpleasantness” of the past year behind him. A writer asked the young player what name he liked to go by; he’d seen Rich, Richie and Dick.

“To be truthful with you,” Allen said, “I’d like to be called Dick. I don’t know how ‘Richie’ started. My name is Richard and they called me Dick in the minor leagues.”

The reporter felt it necessary to investigate this claim. Having satisfied his journalistic standards, he reported that Allen was being truthful:

“Somewhere along the line the Phillies goofed. Their roster lists him as Richie Allen and it’s that way in the NL records. But in the commissioner’s office it’s Richard Anthony Allen. The Phillies ought to get this straight because Allen will be around for quite a spell.”

Those comments ran in newspapers nationwide. It was the beginning of his big league career, and Richard Allen had asked to go by Dick.

Richie it was.

Having hit his way out of a bad situation, Allen now hit to keep his place. He quickly established himself as the Phillies’ everyday third baseman and helped keep the team in a pennant chase that went down to the final day of the season. He started all 162 games and hit .318 with 29 home runs, earning the National League Rookie of the Year Award.

His physical gifts were unmistakable. Allen was 5’ 11”, 187 pounds, with a 32-inch waist, “an upper torso that formed a perfect V, and the forearms of a blacksmith,” one writer recalled. Armed with a heavy 40-ounce bat, he became the artillery corps at the center of any lineup.

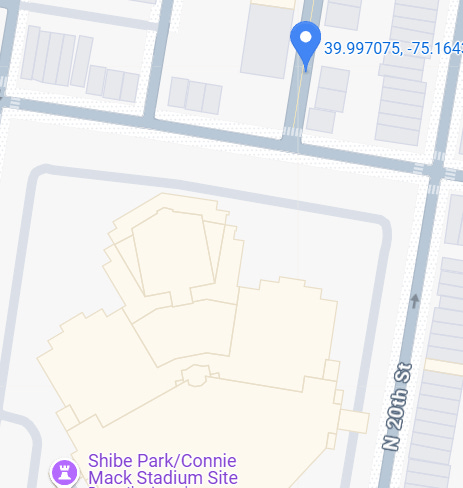

Allen wasn’t perfect. He led the league with 138 strikeouts and he struggled on defense, committing 41 errors at third base. This was hard for the fans at Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium to tolerate, and Allen was regularly booed. At least in Philadelphia he had a manager who tried to protect him. Gene Mauch once complained that “Philadelphia fans would boo the national anthem,” and lamented that a player like Allen, with exceptional talent, was “expected to be exceptional every minute of the day.” On the other hand, Mauch insisted on calling him Richie.

Allen continued his offensive excellence in 1965, including a legend-building moment on May 29 when he hit a 510-foot “transcontinental” home run that cleared a billboard on top of the roof of Connie Mack Stadium, some 80 feet off the ground. An usher outside the park saw the ball hit a tree 50 feet up Woodstock Street.

The pitcher, Larry Jackson, couldn’t watch, but he also couldn’t believe what he’d missed. “It went over the billboard?”

Allen hadn’t watched either. “I didn’t clock it. But it was the first one in three months that felt good.”

On July 3, 1965, Allen was named to his first All-Star team, but the high wore off quickly. The same evening, with hundreds of fans already inside the park, he was involved in an ugly altercation with a White teammate, Frank Thomas. Amid some batting practice roasting, Thomas apparently sought to criticize what he felt was the young slugger’s high opinion of himself, mockingly referring to Allen as Muhammad Ali. Allen punched Thomas on the chin, and Thomas, still holding a bat, swung it and struck Allen on the shoulder.

“It’s the sort of thing that could happen between two people in any sort of business,” Gene Mauch told reporters.

By the end of the next day, Frank Thomas was shipped out of town, bound for the Houston Astros. He was a bench player near the end of his capacity to contribute, and Mauch explained it to him plainly: “That’s what happens when you’re 36 and the other guy is 23 and leading the league in hitting.”

The Phillies told the other guy he’d be fined $2,000 if he talked about what had happened in the press. Informed Thomas was out there giving his account of the fight, Allen could only shrug: “What fight?”

Thomas had apparently made some fans in his season-and-a-half in Philadelphia, and some of these ardent rooters took to unfurling “WE WANT THOMAS” banners and booing Allen at the slightest provocation. It must have been surreal for the Pennsylvania native to see those banners. He’d come so far from Little Rock and achieved so much, but the signs telling him he wasn’t wanted had followed him home.

Allen’s relationship with Philadelphia fans festered so much that he eventually began wearing a batting helmet on defense to protect himself from the occasional projectile potshot from someone in the crowd.

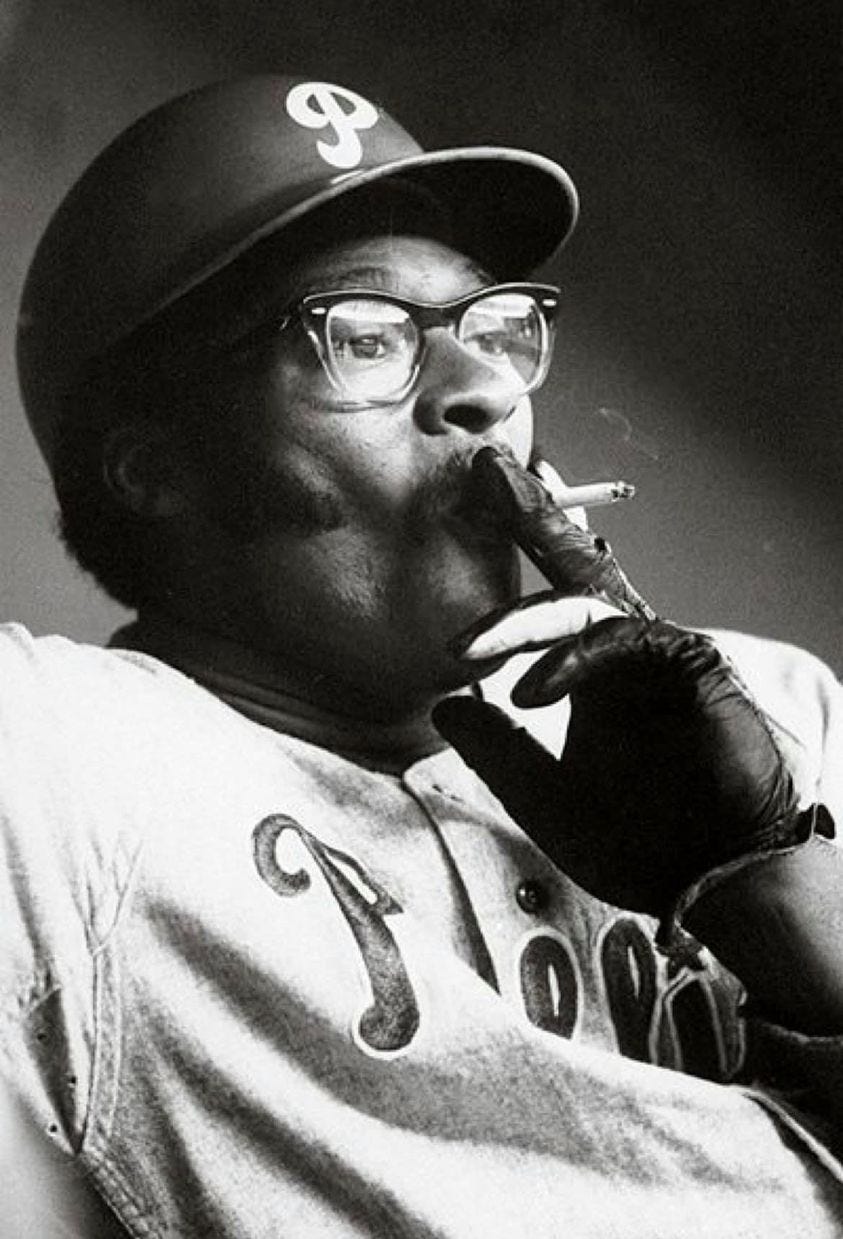

He had one of his best offensive seasons in 1966, but he plugged away at his own double-standard, “keeping his own hours,” arriving late for practice and even games. He also struggled with alcohol abuse. In his autobiography, Allen admitted he regularly drank during home games:

The Phillies had bathrooms right off the dugouts. One of the guys around the park would put a beer in the towel dispenser for me. I could find a cold green one in there in the third and seventh inning–and the fifth inning, too, if we were winning.

Allen’s off-field problems undercut his three-year run as a power-hitting All-Star who regularly earned MVP votes. By 1967, he made it clear he wanted to be traded. The Phillies tried to close their ears, but Allen, now a star, wasn’t going to put up with that again. He began trying to force management’s hand by playing even faster and looser with the team rules. These protracted battles went on for several seasons, contributing to the firing of Gene Mauch and the resignation of another manager, Bob Skinner. Despite the conflict, it took the Phillies until 1969 to make a deal for Allen that they could live with, and by then Allen had earned a reputation he’d never fully shake.

He’d eventually find a use for the name the Phillies had thrust upon him. Looking back on those acrimonious years, he saw Richie as the problem child, the stubborn one who was easy to wound and slow to heal. Richie feuded with writers and teammates. Richie was the outlaw.

Dick, on the other hand, was one of the most dominant players of his generation. Dick was team-first, win-first, and fans cheered him for hitting majestic home runs. “Dick was always bailing [Richie] out,” he said.

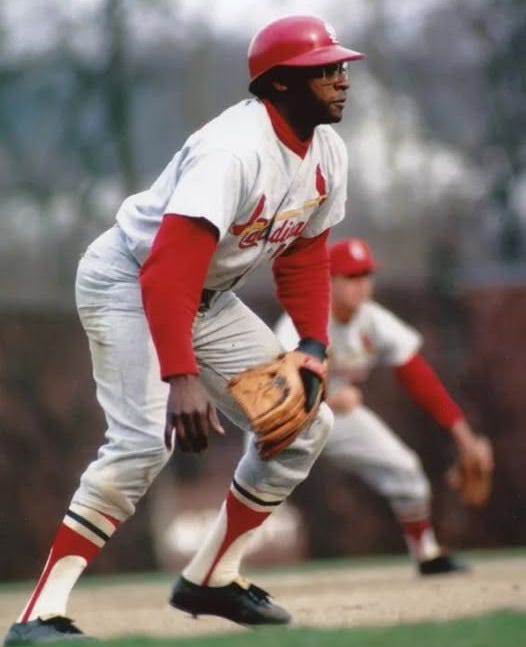

In 1970 he was finally traded, to the St. Louis Cardinals. There, Allen believed he had a chance to start fresh. He held out for most of spring training to boost his eventual salary, but after he signed he hit .279 for the Cardinals and sent 34 of those hits into the stands, with no drama away from the field. It was a fine season and he liked the vibes.

“In St. Louis, the fans care about the game,” he wrote in 1989. “In other cities, especially New York and Philly, it’s all about personalities. Here, they talked about strategy–the hit-and-run, the squeeze play, the defensive alignment. It was great therapy for me.” Unfortunately the fit wasn’t quite mutual.

He was told the Cardinals wanted to prioritize defense—not his strongest suit—and after the season Allen was traded to the Los Angeles Dodgers. Playing multiple positions for Los Angeles, he had another fine offensive year, hitting .295 with 23 home runs, but he struggled to find a home on defense, and he didn’t love the atmosphere in Dodgerland. “With the Dodgers we had a lot of veterans and the enthusiasm just wasn’t there.”

Allen himself was unenthused by the fan-facing meet-and-greet requirements the Dodgers imposed, and the controlling O’Malley family, who owned the Dodgers, had a sensitive ear for discordant notes. On December 2, 1971, Allen was traded to the Chicago White Sox.

In what had become an annual rite of spring, Allen refused to sign a contract and report to his new team. The matter of his fee needed to be settled, yes, but he also seemed footsore and weary being passed along. From his earliest days in Philadelphia he consistently framed his relationship with his team and the fans in terms of belonging. He wanted to be wanted, he wanted to be embraced, and when that didn’t happen, he felt alone again.

“It could have been a joy, a celebration,” he wrote of his life in baseball. “Instead, I played angry. In baseball, if a couple things go wrong for you, and those things get misperceived, or distorted, you get a label. I was labeled an outlaw, and after a while that’s what I became.”

Now Allen wasn’t sure he wanted to start over again, and he really wasn’t sure he wanted to do it in an unfamiliar league with a team of young players he viewed as “kids,” in need of more leadership than he was comfortable providing.

The White Sox, however, were sure—and desperate. They needed right-handed power to fill out a lineup that had showed promise in 1971, and they needed a first baseman. Dick Allen was what they needed.

They offered him a $5,000 raise, to $110,000. That, unsurprisingly, didn’t work, so they told him to name his price. Allen named $135,000 and the Sox’ general manager, Stu Holcomb, said yes. Allen backpedaled.

The team’s second-year manager, Chuck Tanner, happened to come from the same area of Pennsylvania as Allen and knew him and his family. Tanner visited the home of Era Allen, Dick’s mother, twice that winter, trying to get Allen to take yes for an answer. At one point the Sox had an agreement with Allen’s agent/advisor, but Allen said the agent didn’t speak for him. Spring training began.

The long and winding delay played right into people’s misgivings about trading for baseball’s outlaw. In Chicago, Tribune columnist Robert Markus planted his flag firmly in that camp. In a column on March 21, he advised the Sox to “stop throwing good money after bad.”

The revival on the South Side last season was accomplished less through individual heroics than through the spirit of togetherness fostered so well by rookie manager Chuck Tanner. Richie Allen is a divisive influence on the White Sox.

If Allen wouldn’t sign, Markus wrote, trade him. “I don’t think you’re going to get much for him, but whatever you get will be more than you’ve got right now. This looks like a good time to cut your losses and run.”

The Sox set an April 1 deadline to sign Allen, and a few days before that, he appeared in Sarasota, Florida to personally participate in the negotiations.

After several hours of meetings with Holcomb over several days, Allen finally signed a White Sox contract, for the same amount he’d earlier requested, $135,000. It was the most any Chicago baseball player had ever earned, representing a quarter of the Sox’ entire player payroll.

“I was a little deflated,” he said of his holdout. “That was the major holdup. I’m very happy now. They gave me their word that they really wanted me. I feel it is a privilege to play for Chuck Tanner, who I have known since I was a kid. He has made me feel really wanted and I’m going to give the White Sox my best.”

Holcomb said the team had come to a “verbal agreement” with Allen assuring him they wanted to retain his services over a longer term. It wasn’t in writing, but it was true.

A reporter asked the veteran what name he wanted to go by. He’d seen Rich, Richie, and Dick. What did Allen want to be called in Chicago?

“Never late for supper,” Allen said, disarming the loaded history of the question with a joke. “I would much rather be called a winner when this thing is over.” Perhaps he expected the conversation to move on, but it didn’t. The writers awaited a real answer. What did he want to be called?

“Dick will be all right, I guess. I don’t really mind. I’ve been called Dick ever since I was a kid, but when I was in Philly, they started calling me Richie.”

After a 41 day holdout, Dick Allen was asked how long he’d need to get ready to play for the Chicago White Sox. “As long as it takes a pitcher to warm up,” he said.

Displaying his usual mastery of the holdout, Allen had managed to time his arrival perfectly, avoiding six weeks of spring training he felt were unnecessary. He’d stretch out for a few days, hit a few balls, and be ready the White Sox home opener, scheduled for April 6.

But there arose a small complication. On April 1, 1972, the very same morning Allen signed his White Sox contract and proclaimed himself eager to play, player representatives from all 24 major league clubs voted unanimously to begin a general strike. It was the first coordinated strike in the history of North American team sports. Dick Allen showed up hungry, but supper was going to be late.

Next week, we’ll share some stories from baseball’s first major labor action and see how long it takes for the sport to get its collective act together.

On April 14: “Strike One”

When the 1963 season began, there was another Black player assigned to the Little Rock club: 20-year-old Ferguson Jenkins, a promising pitching prospect. One imagines the conversations the slugger from eastern Pennsylvania and the pitcher from Chatham, Ontario had early that spring, trying to make sense of their new surroundings. After four lackluster appearances, Jenkins was sent down to the Single-A Miami Marlins, and Allen was alone.

It’s SO true about the Philadelphia fans. My wife is from there & she told me how they threw snow balls at Santa at an Eagles game.

I’ve mentioned previously how I was treated at a Philly’s game wearing my Yankees jersey so I believe how they treat Allen.

Far as someone not knowing names I had to tell a neighbor after almost two years my dog’s name isn’t Ginger… it’s Cooper. As you I felt kinda weird but I thought it was time he got it right. Guess I should not have waited that long too. I’m bad.

Loved the personal story, Paul