After more than a half-century as an exclusive fraternity of 16 teams, eight per league, major league baseball expanded—the American League in 1961 and the National League in 1962.

Expansion teams were not expected to be good. The system which created them all but guaranteed this. The existing pool of talented players could not cover so much new territory so quickly. The new teams were built from the grudging cast-offs from their more-established peers, supplemented by the greenest of rookies and the grayest of veterans, as well as anyone else who was still available and willing to sign. The early years for a new club were an investment in the future. As the organization built the infrastructure and pipeline which would be needed to compete in the long run, they’d have to field AAAA teams in front of empty stands.

Three of the ‘61-’62 expansion teams met all expectations and finished in either last place or third-last, which felt about right to everyone in terms of performance.

The fourth team was the New York Mets. There was nothing right about what they did in 1962, or how people reacted to it.

Expansion teams were not supposed to be immediately popular, either. A sports team’s popularity has long correlated with its level of success on the field. You do not need a sociology degree to appreciate that, for whatever evolutionary reason, human beings find winning extremely fun to watch. New teams could not offer much of this.

When the expansion Los Angeles Angels and Washington Senators entered the American League in 1961, they finished in eighth and tenth place, respectively, in the AL standings, performances that were good for 17th and 18th place—dead last in baseball—in annual attendance. All of this made sense.

More of the same was expected after the National League expansion of 1962, which added the Houston Colt .45s (Astros) and the Mets. That first season, the Colt .45s were not wholly terrible and had the good fortune to play in the same league as the Chicago Cubs, who helped them to an eighth place finish and a very good 11th place at the turnstiles. All of this was according to the formula. The team (slightly) overachieved on the field, and the fans turned out in proportional response.

And then there were the Mets. They also finished last—emphatically last. Historically last. Spectacularly last, as last as any “major league” team possibly could. And yet, this disgrace of baseball and cautionary tale of the expansion era somehow drew over 900,000 people, finishing just behind the Astros and ahead of eight other clubs, even the Milwaukee Braves, who had a winning record. None of this made any sense.

One dedicated observer believed the team’s success (at the box office) was the result of a strange malady that had begun circulating in New York City. He fully described the condition in 1964, not in a medical journal, but in the pages of the Saturday Evening Post. Trying to explain to America what was happening in New York, prominent local columnist Jimmy Breslin dubbed the condition “Metsomania.” With that, the city and the incredulously-watching nation finally got a name for the condition which had liberated so many otherwise rational, functioning New Yorkers from their senses.

Note: I had planned to post a photo of Jimmy Breslin about here, but then I happened upon the video of his opening monologue when he hosted Saturday Night Live in 1986. I’d not come across this before, so I watched it. Forced to do comedy in an unfamiliar format, Breslin spends half the time talking about…the 1962 New York Mets.

Here at Project 3.18, we begin with the story of Metsomania: from its appearance in 1962 through 1969, when–in a moment Breslin could have scarcely imagined five years before–a striking new variant burst out of the boroughs and swept across the country.

According to Breslin, Metsomania was triggered by prolonged exposure to the Mets, “a team so bad at playing baseball that it has stepped out of sports and has become a driving force in the city’s culture.” Metsomania was also a response to the collective trauma of a decade earlier, when the owners of the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants left their generational homes in New York and absconded to California, taking two-thirds of New York’s baseball tradition with them.

New York’s remaining team, the Yankees, had done little to help the city get over its losses. The Yankees, Breslin explained to the Saturday Evening Post’s national audience, were for the bankers, the big-wigs, and, well, you people—the out-of-towners.

The Dodgers and Giants had been for New Yorkers: a label in Breslin’s taxonomy which covered the vibrant, teeming throngs of working-class, immigrants, and strivers who made their home in a tough place to live. The continued presence of the Yankees could do little for these New Yorkers, who had been robbed of their cultural birthright and left unmoored.

One of those adrift was William Shea, a prominent and successful New York lawyer (but nonetheless a Breslin “New Yorker” at heart). Stung by the rejection of his peers who owned the Giants and Dodgers, Shea made it his mission to return National League baseball to New York, and he did not take any half-measures. Shea helped spearhead a new, upstart league, the Continental League, intended to gather up all the cities that baseball had put off, ignored, or, in New York’s case, robbed. The two established leagues ultimately agreed to expand their organizations to end the threat, and Shea made sure New York was first in line for a new NL team.

“I did this thing on a principle,” Shea told Breslin in 1964, sitting in the Diamond Club high atop the stadium that bore his name.

“I said, ‘I’ll go all the way.’ I was born in this town, I was raised in this town, I went to school in this town and I make my living in this town. We supported the Giants and Dodgers–the fans, not the owners of those teams. When they said New York wasn’t good enough for them, I said the hell with that. I’ll show everybody what New York is.”

He looked around, quite satisfied. “Here we are, let’s drink to it.”

Breslin’s article describing Metsomania was not his first foray into the Mets’ wild-eyed community. In 1963, he wrote a book on what had unfolded during the Mets’ inaugural season, but since Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game? had been published, the team had gotten no better while enthusiasm among their followers somehow veered towards fanaticism. This had initially troubled Breslin. Surely New York saw itself as a winner and wanted to associate with winners and not…whatever the Mets were. What did the Mets show everybody about what New York was? In his book, Breslin put roughly this question to his psychiatrist:

“I like the Mets. I’m starting to die every time they play. What’s the matter with me?”

“It is pity,” the psychiatrist responded. “Pity is kin to love.”

“But I like to be a winner,” Breslin said. “Why can’t I root for the Yankees? I hate the Yankees.”

“You can’t pity the Yankees,” the doctor said.

With a year’s further contemplation, Breslin had worked things out for himself, deciding that the Mets were counter-programming to the “conformity-conscious, anonymous New York,” epitomized by the Yankees—a team famously compared to U.S. Steel in terms of fun factor—and their Rockefeller fans. Baseball (of a sort) restored to them, Breslin’s real New Yorkers had “stepped off onto one of those dippy little tangents,” as happened from time to time in the city of stress, pressures, and expectations. With the Mets, Breslin wrote, “there was a chance to laugh every day.” As long as you were in on the joke.

“It was impossible not to be a Met fan,” one New Yorker recalled, “because the Mets, they win when you want them to win and lose when you want them to lose. You used to expect them to make errors and mistakes, and they did. They were funny.” By those standards of comedy, the Mets came into the world funny and quickly grew hysterical.

Early on in their first season, the Mets ran into a bit of a hot streak where they won nine out of twelve and had moved to eighth place in the ten-team league. The general manager, George Weiss, felt brave enough to publicly share his feeling that a seventh place finish might be in reach for the new team.

It was as if someone had given the Mets a secret code word. The team proceeded to lose seventeen games in a row. This was about the point that New York really sat up and took notice of their new baseball team, from which they had expected mediocrity and seemed to be receiving something else altogether. After the team’s loss marathon, there would be no more questioning of their credentials. The Mets were chasing history. New York could root for that.

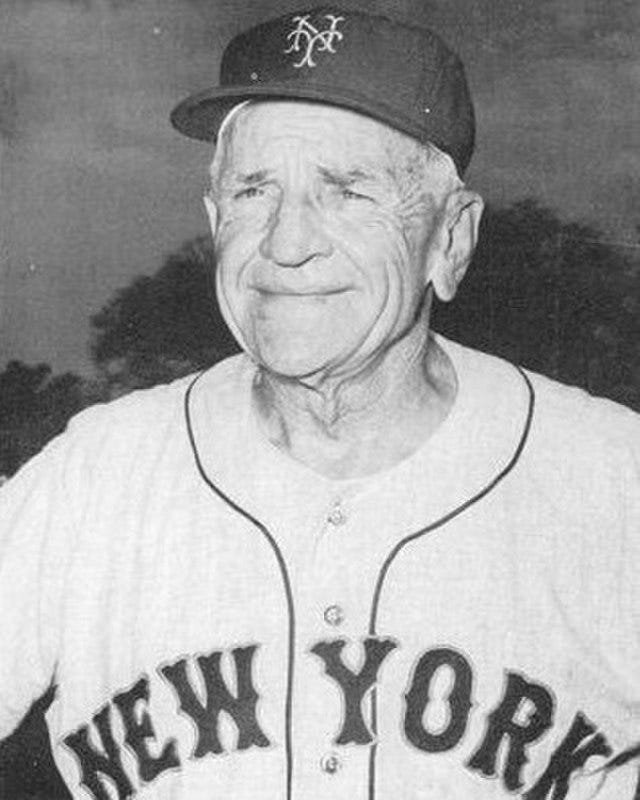

From their beginning, the Mets needed someone the city trusted to build a bridge from Old New York to its new team, someone who would foster a new culture that would never, ever be compared to U.S. Steel. They found the perfect someone working as the vice president of a bank in Glendale, California.

After more than a decade of championships while managing the Yankees, Casey Stengel had become a legend of the city and an icon of baseball’s Golden Age. 71 years old when he left the bank to join the Mets, Stengel, stooped and increasingly wizened, cut a comical sight in a baseball uniform. But his specialty was stand-up, or, at his age, sit-down. For years, Stengel’s non-sequitur, monologuing style had charmed the media and the city, providing a counterpoint to the generalized Yankee stoicism, and his quirks became even more pronounced in his advanced years. Stengel was as hard to understand as the Mets, just as loved, and just as funny, making a perfect match.

Stengel understand that his was something of a caretaker assignment. He knew that this team would never win on his watch, maybe even in his lifetime. Instead, he would entertain. The manager saluted the fans from the field, he signed autographs, he even led the in-house marching band. When he was supposed to be managing, Stengel would sometimes try to hex opposing batters from the dugout steps. On other occasions, he was spotted taking naps in the dugout. When awake, he helped build the brand, playing the character the fans wanted to see. And of course, he gave colorful, candid speeches.

In 1962, he ironically branded the first Mets club as “Amazin’” for their ineptitude, and the more people saw of the Mets, the more they realized the depth of truth in Stengel’s choice of descriptor. Winning or not, the Mets’ manager wanted people to know that something remarkable was happening at the Polo Grounds, something they ought to see. “I been in this game a hundred years but [managing the Mets] I see new ways to lose I never knew existed before."

Here is just one of those ways:

Richie Ashburn, the Mets’ first center fielder, had a problem. Shallowly-hit balls to the outfield brought the shortstop, Elio Chacon, who spoke almost no English, into Ashburn’s territory. To avoid collisions, Ashburn decided to learn how to call for the ball in Spanish. During an early-season game, he came racing in to catch a shallow fly ball, calling Chacon off in the shortstop’s first language. Chacon heard the calls, understood them, and stopped short, yielding to Ashburn. Imagine the center fielder’s surprise when, as he arrived under the ball, he nonetheless found himself knocked in one direction while the ball went another.

When he woke up, Ashburn learned he’d been walloped by Frank Thomas, the left fielder, who’d also come in to make a play, and—not speaking any Spanish—didn’t understand Ashburn was calling him off.

Did these sorts of miscues happen to most teams from time to time? They did, absolutely. The difference was that the fans, with little else to root for, decided to make poor play the star.

Acquired from the Baltimore Orioles in May 1962 to fill in for an injured Gil Hodges at first base, Marvin Eugene Throneberry confronted a hopeless mission. Hodges was the most revered and accomplished player on the team, nearing the end of a long career with the Brooklyn (and Los Angeles) Dodgers spent being one of the best offensive first baseman the game had seen. Even if he played the most impressive baseball of his entire career, Throneberry was about to be swallowed up in Hodges’ shadow.

So, Throneberry did not try to do that. Instead, arriving on a 5-16 club, he seemed to have decided to lean in, as he immediately began to play some of the worst baseball of his or anyone’s life, often with a theatrical flair. Breslin, in particular, was enthralled, made apparent by his decision to describe some of Marvelous Marv’s antics to the SNL crowd nearly a quarter-century later. Breslin covered the best instance in his monologue, but there were many others. A botched rundown here, a dropped infield fly there, and soon Throneberry had succeeded in making everyone forget about Gil Hodges.

Dubbed the most Amazin’ of them all, Throneberry got his own chant: “Cranberry, strawberry, WE LOVE THRONEBERRY!”

He got his own fan club, who rooted for miscues and made shirts that spelled his name backwards, “VRAM,” because that, they felt, was surely what Throneberry would have done (by mistake) if he were making the shirts himself.

At the height of his influence that season, over a hundred letters a day (fan letters, not death threats) arrived at his locker. “The hell of it all is, I’m really a good fielder,” he insisted.

One former manager backed this up:

“Marv never made plays like they say he makes now. I guarantee you he never did. If he ever played that way for me, I would have killed him with my bare hands.”

Made prince of the Metsomaniacs, Throneberry got to spend his baseball twilight—normally a wistful, frustrating time for a journeyman player—as a New York folk hero, and then parlayed his brand into a successful second act doing beer commercials. Very un-Metsian, in the end.

Like Stengel, “Marvelous Marv” eventually embraced his role and the culture that had elevated him far beyond his merits, saying: “You live with us, you get like us.” That seemed to be epidemiologically correct. With Stengel, Throneberry, and a host of other woebegone players as vectors, the contagion spread quickly. In their second year, the Mets kept their toes firmly squished into the terra firma of last place but grew their following, drawing over a million fans and becoming the seventh-most popular team in all of baseball.

“[The Mets’] followers,” Breslin wrote, “living in a city which is a success by itself, and which is filled with people who are successes and others who are in search of success, demand absolute incompetence from their ball club. Anybody can root for a winner. But to be with a loser calls for a special flair.”

“They are without a doubt the worst team in the history of baseball,” Bill Veeck declared. “I speak with authority. I owned the St. Louis Browns. I also speak with longing. I’d love to spend the rest of the summer around the team. If you couldn’t have any fun with the Mets, you couldn’t have any fun any place.”

With such reviews pouring in, it didn’t take long before Mets games became one of the hottest tickets in town. Fans who came to the Polo Grounds or, later, to Shea Stadium, were given the opportunity to sit in what was essentially the live studio audience for one of baseball’s purest comedies. Though they would often do their best to hide it, even some Yankee fans turned their pinstripes. “I come here a lot,” one such fan confessed to Breslin. “I’ve known Casey Stengel for a lot of years. I don’t think the poor guy should be left alone at a time like this.”

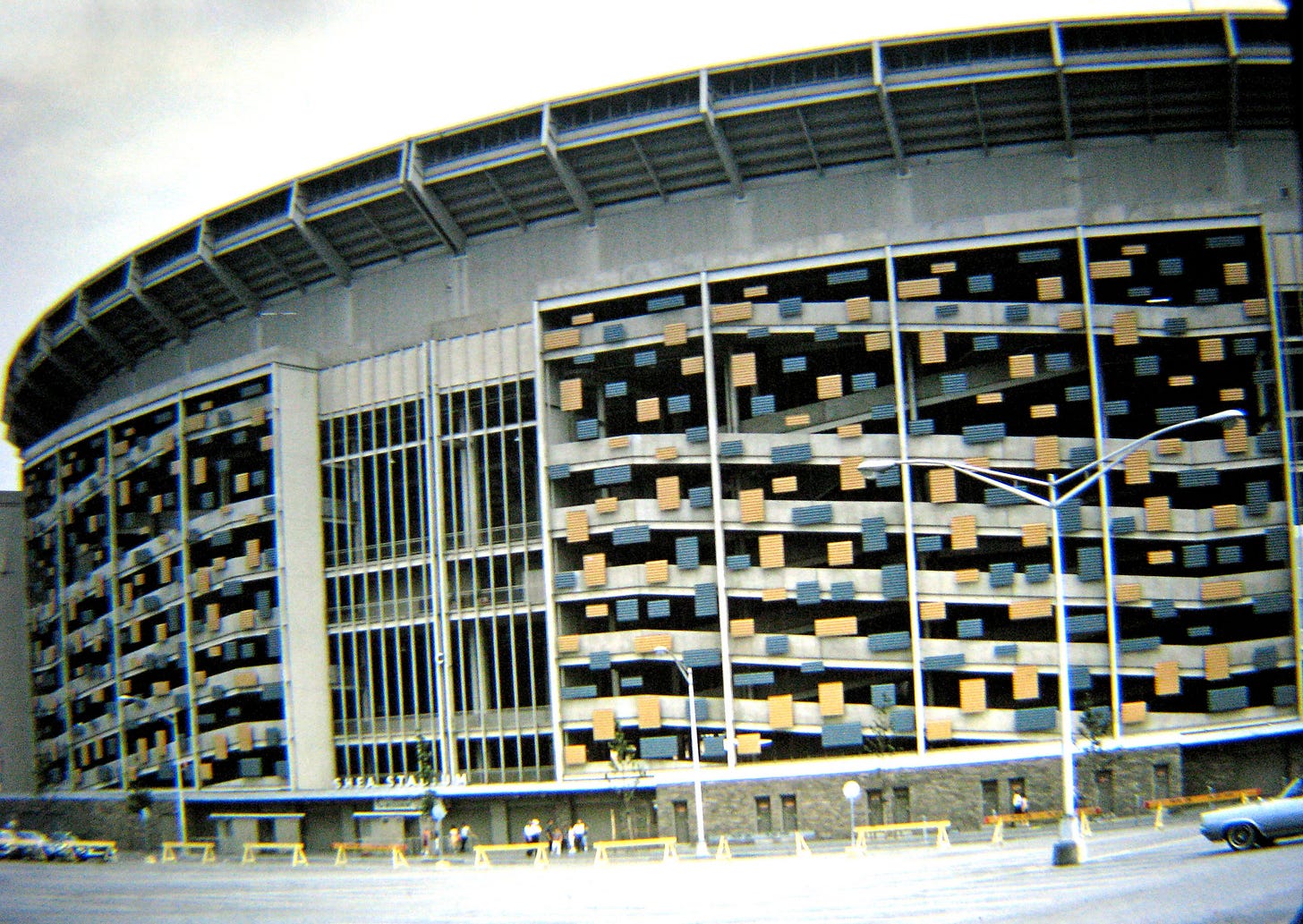

The club spent its first two years in a home that matched their particular brand of ennui, bunking with the Giants’ ghosts in Manhattan’s old Polo Grounds while their own big top/sanitorium was under construction in Queens. Opened in 1964, Shea Stadium met New York’s growing commuter population halfway, sitting across the street from the World’s Fair grounds in Flushing Meadow, which at that time was considered a boundary zone between the city proper and its more suburban reaches.

Bolstered by Shea, Queens succeeded Brooklyn as a bastion of the “middle-class” New York experience. Awash in the perpetual roar of jet turbines from nearby LaGuardia, the borough’s hedge-bound homes and newly constructed apartment buildings reflected a decade of growth as migrants from other, more crowded and in some cases crumbling neighborhoods found refuge on Queens’ safer, less-congested streets, many of which were shaded by actual trees.

In a booming neighborhood and a shining new stadium, the 1964 Mets, who were universally expected to “run to the National League cellar like Kansas farmers with a cyclone in sight,” nonetheless sold 1,732,000 tickets. Meanwhile, the Yankees, who were expected to win another (perhaps final) dynastic pennant and did, drew only 1,305,000.

Not only did they out-draw the Yankees, the Mets’ seasonal attendance was second only to that of the juggernaut Los Angeles Dodgers. During this time period, the Dodgers won two World Series and were consistently the first or second-best team in the league, and they ran away with the attendance crowns year in and out. The Dodgers’ box office success was easy to understand, but how could their opposite do just as well? Perhaps Mets fans knew they were witnessing history, because, as we will see in Part 2 of our story, the 1960s Mets had few equals–past, present, or future–when it came to losing baseball games until, all of a sudden, they became terrible at that, too.

Next: The Mets vs. the Cyclone

Thank you for reading Part 1 of “Metsomania: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment.” Here’s a link to Part 2 of our story.

Paul, I enjoyed the Breslin bit - newspapers are still making enemies, by the way.