Looks Like Rain

Damp conditions make for short fuses

It’s time to talk ejections! If you missed it, here’s where we explain what we’re doing in this new segment.

We’ll start with the wet ones, and we’ll do that several different ways over the next few installments. Today we’ve got a Rockwellian dilemma, baseball deja vu, and a little poetry.

There have been (roughly) 25 ejections from major league baseball games for reasons related to “field conditions.” That’s 25 people, all of whom complained too much (or, as we’ll see, too creatively), drawing the ire of a sodden and fed-up umpire who proceeded to throw them out of the game.

It’s possible that some of these ejections do not relate to rain or precipitation (we did not check them all), but most probably do, as “field condition” is how all of the water-related escapades we’ll look at today were noted.

This group of ejections share a common root: the weather dilemma.

Deciding what to do when it starts raining mid-game presents a quandary for umpires. In order for a game to officially “count,” the losing team must have taken their turn to bat in the fifth inning. Any game that does not reach that point may be “postponed” (essentially erased) and re-started on a different day. This is a much less frequent outcome in baseball’s current context, but for much of its history, rain has washed out nascent games.

The rules inevitably lead to gamesmanship from players and managers. The team that is ahead wants to keep playing a little longer, moisture in the air being good for the skin and good for the soul, after all, while the team that is behind complains that they are soaked, half-blind, and ready to pack it in and try again another time and, hey, was that lightning over there to the west?

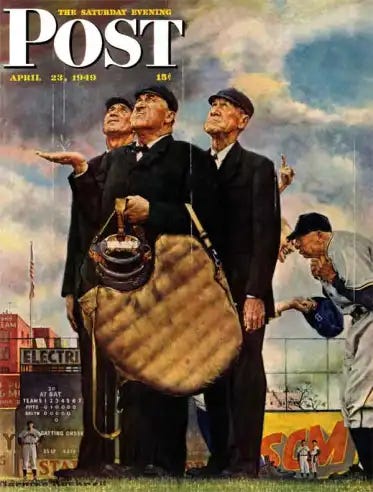

The weather dilemma is famously and wonderfully depicted in Norman Rockwell’s beloved painting Tough Call.

Actual major league umpires and managers posed for Rockwell in 1948. In the resulting scene (which debuted as a Saturday Evening Post magazine cover the next year) an umpire crew, led by Beans Reardon, weighs their options while trying to ignore two posturing rival managers nearby. The inclusion of the managers reveals Rockwell’s deep understanding of baseball tradition.

Whenever the weather dilemma arises, players and managers theatrically plead their case in hopes of swaying the umpire’s decision. These performances are distant cousins to the bodily flops of soccer and basketball—no matter how hard the hit actually was, a good show about getting hit may help manifest the desired foul call from an official. On the other hand, overdoing it may just make you look ridiculous.

Here are the stories of two rainy-day performances that went a little too camp for the umpire’s tastes, ending their days (but not the games).

Runner-up: Frankie Frisch, manager, 1941

On August 19, 1941, the Brooklyn Dodgers hosted the Pittsburgh Pirates at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, New York, in front of 10,000 fans. Both teams remained in the hunt for the pennant, but the Pirates were a bit behind both the Dodgers and the St. Louis Cardinals, who had been rained out in Boston, creating an opportunity for Brooklyn to pull ahead, if they could get the day’s two games in.

The doubleheader was itself the product of a rained-out contest from July, which, combined with the games’ relevance to the unfolding pennant race, probably made the umpires even more committed than usual to playing ball.

Leading the lagging Pirates was Frankie Frisch, the famous Fordham Flash, already baseball royalty after his years and accomplishments as a player, a player-manager, and now just a single-hyphenate again as a manager in his mid-forties. Frisch was ejected an astounding 100 times during his career, and most of those came when he was acting in a managerial capacity. We’ll devote a future piece to some of his other Great Works, several of which we included, anonymously, in our introductory post on ejections.

The Pirates took a thrashing in the opener, the game “wrapped in cellophane” for the Dodgers by the middle innings, prompting bellows from the sparse crowd to “Start the next one, already!” But the Dodgers were having too much fun, sending 12 men to the plate in one turn, a 35-minute performance that earned remarkably few cheers. The Dodgers (also the “Brooks,” in the parlance of the times) eventually won 9-0.

The second game (often called the “afterpiece,” a lovely baseball term of art) began in what third base umpire Jocko Conlan recalled as “a slight mist.” The Dodgers went ahead 1-0 in the early innings, and Frisch had apparently seen enough.

The Pirates began slow-walking every part of their duties, earning boos from the crowd and scoldings from Conlan and the other two members of the umpire crew (the familiar-sounding Beans Reardon and Larry Goetz).

In the third, Frisch called out, “What’s the matter, Jock? Don’t you see this rain? Haven’t you got enough guts to call the game?”

“Haven’t you got enough guts to play it?” Conlan called back. 15-all.

The next inning, Frisch came out of the dugout to take his spot in the third base coaching box, twirling a black umbrella over his head while reporters gathered near the dugouts snapped pictures and laughed. Conlan later admitted he cracked a smile himself, but disrespect was disrespect and there was only one remedy, which he soberly applied.

The Dodgers went on to win the afterpiece (it’s catchy!), and the day’s two victories helped secure their eventual pennant, though they would lose the World Series to the New York Yankees, four games to one. That’s the story, but there are two noteworthy postscripts we must share.

The next day, newspapers across the country carried a similar blurb on the game but one paper, the Louisiana Shreveport Journal, somehow ended up with a remarkable scoop, which they inexplicably buried as a footnote at the bottom-left corner of a hodge-podge of news bits on page 11:

”FRANKIE FRISCH FIRED”

Really? Frisch lost his job over that? This guy was a baseball legend in his own time and he got fired in the middle of a pennant race over a harmless gag? Even Conlan thought it was funny!

In the 1940s, newspaper copy was produced on typewriters before being set into metal plates for printing, a multi-step process that left numerous typographical errors in the final newsprint, including one in the title of that blurb.

In fact, Frankie Frisch had only been fined—by the National League president at the time, Ford Frick. For engaging in a “vaudeville act” on the diamond, Frisch owed the league $50. In 1941, that was a bit of money, the equivalent of $1000 today. “Now I am mad,” Frisch was quoted as saying, and he ripped the telegram “into some 50 pieces” (the equivalent of 50 pieces today).

The mislaid headline also missed a huge opportunity, which we will now gladly capitalize on. It should obviously have read:

“FED-UP FORD FRICK FINES FRANKIE FRISCH; FRUSTRATED FORDHAM FLASH FLIPS.”

The second postscript is that there seems to be a widespread belief that this very incident actually inspired Rockwell’s Tough Call, which was painted seven years later.

In support of that theory is the fact the painting features the Pirates and Dodgers, and that two of the umpires Rockwell later depicted (Beans Reardon, center, and Larry Goetz, left) worked this particular waterlogged episode of Dodgers/Pirates history.

Against is, well, a lot. Conlan—the umpire that actually gave Frisch the boot—is not depicted in Tough Call, nor is Frisch or his umbrella. Further, the painting showcases the classic form of the “weather dilemma” and archetypal histrionics from both managers, which was not what happened in 1941.

What we do know is that Rockwell attended a Pirates/Dodgers game at Ebbets field on September 14, 1948 to obtain visual references for the painting, and that day’s umpire crew are the three officials depicted (Reardon, Goetz, and Lou Jorda). Rockwell most likely decided to make a painting about “the weather dilemma” and incorporated the visual elements of the game he saw into the piece.

The Project 3.18 Take is that the similarities between the Frisch ejection and the painting are coincidental. Wading through so much baseball history, it’s rather easy to get tangled up in coincidence, as we will now demonstrate.

First prize: Connie Ryan, player, 1949; special appearance by the Boston Braves’ arson gang

We move ahead about eight years, to September 29, 1949, but at first glance it might seem like we’re stuck in baseball Groundhog Day. Overall there was so much similarity between this episode and the last that we spent about two minutes thinking perhaps we had hopelessly messed up our notes. Not so.

Once again, our story features the Brooklyn Dodgers playing a double-header, once again with significant playoff implications for the Brooks (can we bring this back?), who were in the very last days of a photo-finish pennant race against, once again, the St. Louis Cardinals.

The day’s double-header was (again) a result of a rainout, this one rescheduled from the day before. With only a few days left in the season and given the significant playoff implications, it was a rain-or-shine situation.

Again, the Dodgers would win both games, by somewhat similarly-lopsided scores, crucial wins that would lead them to the World Series, which (again!) they would lose to the New York Yankees, four games to one.

What is different in 1949 is the setting, changing from Ebbets Field in Brooklyn to Braves Field in Boston, where a dispirited and disheveled gathering of just 5,000 people, many wondering what their life had come to that they had paid to watch two games on a miserable fall day featuring the “Worst Chris” of Boston baseball teams, the Braves.

On paper, however, the Dodgers had their work very much cut out for them. They would face both Warren Spahn (Game 1) and John Sain (Game 2) that day, about as bad a two-pitcher draw as you could make in the National League in that era, to the point that people made poetry about it.

A year prior, Spahn and Sain dominated opponents during the Braves’ 1948 stretch run, and the Braves played their hot hands. With the help of some planned off-days and rain days, Spahn and Sain pitched eight times between September 6 and September 18, winning all eight of their games. The Braves’ only two losses in that stretch came in the only two games when someone else pitched.

This get-the-ball-to-LeBron method inspired a Boston sports editor named Gerald Hern to write a verse about it:

First we'll use Spahn then we'll use Sain Then an off day followed by rain Back will come Spahn followed by Sain And followed we hope by two days of rain.

Ultimately, half of Spahn and Sain (the former) would go into the Hall of Fame, but a 50% Cooperstown-bound pitching duo still came in under the credentials of the Dodgers’ lineup that day, loaded as it was with five future Hall of Famers1. In the opener, that sterling crew jumped all over Spahn, the Braves’ 20-game winner, chasing him with five runs in the fourth inning. Boston went on to lose 9-2.

As this was an unplanned double-header, the teams had tried to squeeze the second game in behind the first without messing with the day’s original start time. The result was a second game played in a persistent, uncomfortable drizzle and increasing gloom.

Compared to the highs of 1948, John Sain, the Braves’ co-ace, was already having an off year, and on this day he would have an outing to match the weather. Sain did not survive even an inning of work, managing only a single out while the Dodgers put five runs on him, just as they had on Spahn.

Down big early, strategy demanded the Braves stall and hope the rain would wipe out the game (and their deficit) in favor of yet another do-over in the season’s final days. Boston’s dripping fans jeered and mocked their own team as Brave after Brave walked to home plate as if moving in molasses and oops, sorry, forgot my bat, will be right back. The umpires implacably shooed them along, intent on getting this one to a regulation outcome.

The Braves’ second baseman, Connie Ryan, led off the fifth inning in semidarkness. The team’s stall efforts had failed, so Ryan decided to make an editorial comment by coming to bat wearing what was unmistakably an unflattering black raincoat.

The home plate umpire, George Barr, was not amused, and threw Ryan out before he could hit. This prompted a most remarkable response in the Braves’ dugout, where the players there used newspapers and who knows what else to actually start a fire.

“The small fire burned brightly for about three minutes,” went one casual report, and another newspaperman got the players to explain: they’d made a signal fire so their mates could safely find their way back to the dugout, being forced as they were to bat in the dark. Har har.

No one appears to have been ejected for starting a fire in the base of a ballpark, but sure, the raincoat guy got tossed. Boston’s fire marshal, meanwhile, could not be reached for comment. Well, maybe fire just wasn’t a big concern in Boston ball parks of this era?

Well, maybe not.

No one went to jail and, meanwhile, the Dodgers’ pitcher, Don Newcombe, mowed down the final three Braves hitters, who were almost surely not trying, and, the losing team having had their customary final turn, Barr and the other umpires declared the game official and over.

Two wins in under 15 innings made it a fine day for Dodgers manager Burt Shotton, whatever the field conditions. Afterward, he was asked how the Dodgers had carved up the Braves and their best two pitchers.

“Good pitching, good hitting, and heads up baseball,” Shotton said. “I don’t think any other club ever beat Spahn and Sain in one day. But we did and we couldn’t have done it at a better time.”

Shotton was correct. Spahn and Sain had been beaten back-to-back before, several times, but never on a doubleheader day. But the occasion was even more singular and remarkable than he knew, courtesy of Connie Ryan’s rain attire and the bonfire burning in the dugout as the Braves rooted for a washout. Fire and ceremonial costumes, we should note, are frequent components in collectively-performed “rain calling” rituals from cultures all around the world.

Remember Gerald Hern’s poem? Initially, it didn’t have a title, but when it became rather popular, the verse was condensed into a title which itself became a snappy, tongue-in-cheek summation of the Braves’ starting rotation:

“Spahn and Sain and Pray for Rain.”

Well, on September 29, 1949, the Boston Braves used all three in one day, and still got completely wrecked.

We hope you enjoyed some vignettes for a rainy day! Let us know.

We do promise to include more short-subject work in our ejections segment, but if Project 3.18 comes across a lost symphony, we reserve the right to break out the full orchestra.

Which is what we’ll do next week, as we play the first movement of a two-parter that inspired our recent foray into ejections.

In 1968, umpire Chris Pelekoudas suspected that the Chicago Cubs’ best reliever, Phil Regan, was cheating by applying a foreign substance to the baseball. Pelekoudas made a spur-of-the-moment decision to fight fire with fire by ignoring the rules and devising his own punishment for the pitcher. Instead of ejecting the Regan, Pelekoudas had him stay in the game, where he would be made to “suffer for his defiance,” which is an actual quote that Pelekoudas freely gave. It’s a story of grease balls, planted evidence, and an umpire willing to rend the very fabric of reality to make his point.

On April 15 (we promise): “The Disallowed”

Pee Wee Reese, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Duke Snider, and Gil Hodges

Great post Paul! Made me go and read the article on the Fenway fires and the raincoat wearer!

Thanks Mark! Links are always a gamble but sometimes I try to build a bit around them to really invite the reader to click for the payoff. The fun of writing on the internet. I appreciate your reading and kudos, and I loved the recent Toots Shor piece. That was the first I've seen but looking forward to reading more from you guys!