It's a Trap! - Part 1 of 2

A game in 1949 is forfeited after recent history repeats itself in front of a tougher crowd.

Exploring baseball’s more colorful forfeits, a clear risk-factor is the second game of a doubleheader. We’ve seen fans grow bored of watching their team get pummeled over the course of a long afternoon and seek other diversions, sometimes on the field itself. We’ve seen a combination of weather and darkness create a sense of urgency that tempts players to cut corners. And here’s another big problem with a doubleheader: after the second game, there is twice as much trash.

Such a doubleheader was held in Philadelphia on August 21, 1949, at Shibe Park, a grande dame of baseball antiquity at the intersection of Lehigh Avenue and 21st Street. The ancestral seat of the Philadelphia Athletics, Shibe was also the home of the National League Phillies between 1938 and 1970.

If you can only spare a few moments to admire the architectural features of a demolished ballpark, make it Shibe. The park exterior was done in the style of the French Renaissance, with walls of red brick and sculpted terra cotta, festooned with decorative, baseball-themed friezes, cartouches, and lined with a green-slate mansard roof, trimmed in copper.

Management occupied a tower at the southwest corner, topped with a rounded cupola that was for many years the office of Connie Mack, the A’s Hall-of-Fame owner/operator. Players walking through that entrance likened it to baseball church. Yankee Stadium is today remembered as the “Cathedral of Baseball,” but Shibe Park did it first.

Shibe was one of the first concrete and steel ballparks built in the United States, very much the future when it opened in 1909 and nothing like its rickety wooden counterpart, the Baker Bowl, a few blocks away. The Phillies had evacuated the Baker Bowl right in the middle of the 1938 season, preferring to rent in baseball heaven than rule over a ruin.

By 1949 Shibe could hold approximately 30,000 fans, but capacity was rarely approached. The 1930s and 1940s were lean times for Philadelphia baseball. The A’s were in dire financial straits and would soon be abducted to Kansas City, and the Phillies were so historically bad that a few years earlier new ownership had decided to try and reboot the team, down to a new nickname.

Since 1944, the team had been rebranded as the Blue Jays, the winning name from a fan write-in contest. You might see some vestigial references to “the Jays” in quotes for this story. But despite the change in name, “Phillies” remained in script across the team jerseys, and the team would release the Blue Jays in January 1950, dropping the name and changing their navy-blue motif for a bright red we’d all recognize today.

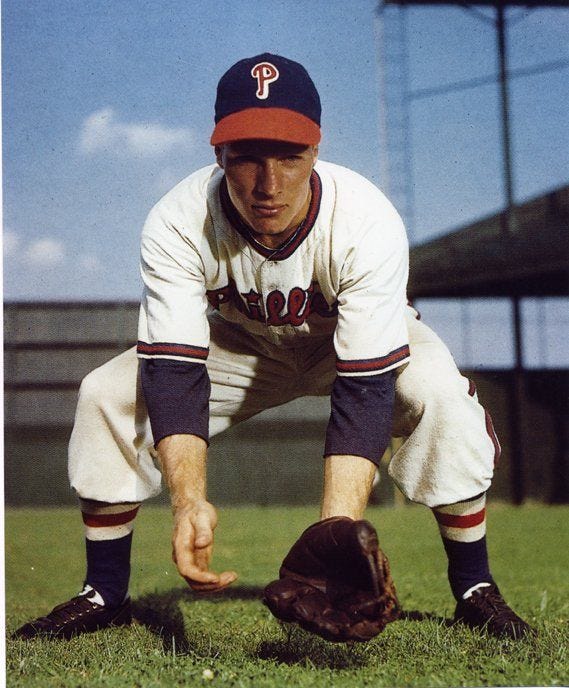

In this final year of their half-life, the “Jays” were turning things around. They would finish with a winning record, breaking a 16-year losing-streak, but 16 games back of Brooklyn and St. Louis, the league’s neck-and-neck juggernauts. Key pieces were in place, including Jim Konstanty, one of the sport’s first “closers,” pitcher Robin Roberts, left fielder Del Ennis, and a 22-year-old center fielder named Richie Ashburn, who debuted as an All-Star in 1948 and earned serious Rookie-of-the-Year consideration and a few stray MVP votes. With Ashburn and a team of young “Whiz Kids,” relevance was close in 1949.

The season’s promise ended abruptly in mid-June, when one of Philadelphia’s heavy hitters, first baseman Eddie Waitkus, was lured into a Chicago hotel room and shot by an obsessed female fan in one of the most publicized examples of celebrity stalking in American history (to that point). Waitkus had been hitting .306 with 27 RBI and 47 runs scored at the time. He survived, but did not return to action until 1950.

“If Eddie Waitkus hadn’t been shot, I think you might have a three-club race,” his teammate, shortstop Granville “Granny” Hamner said in August. “We were three games out when we lost him. It was a terrible blow.”

Without Waitkus, the rebuild sputtered, and the Phillies would have to wait until next year.

The New York Giants were similarly stuck in the middle of the National League, with nothing left to do but battle for third-place money. Such a mid-card match-up drew 19,742 fans to Shibe Park on Sunday, August 21. The crowd was ready for the doubleheader, well supplied with packed lunches and cold beverages.

The latter would have been generally of the non-alcoholic variety, since at this point in time there was no alcohol allowed inside Shibe Park. On a hot August day like this, that made soda (called “pop” in this region of the country during this period) the drink of choice for many fans.

The A’s and Phillies may have been leaders in baseball temperance, but they lagged behind the trends in other areas. Shibe was one of the last ballparks in the major leagues where glass bottles were permitted, but this would change, very soon.

In 1949, regular season games were typically handled by a three-man umpire crew, with one behind home plate and one on each foul line. The umpire in charge for this game was Al Barlick, a nine-year veteran who had become widely respected around the National League.

Lee Ballanfant worked third base that day, and he and Barlick had been together since the latter first arrived in the majors.

“Barlick was the best I ever saw,” Ballanfant said later, “a natural born umpire. Everything he did on the ball field was natural. He had a knack for it: everything was easy for him. And he had good control—nobody ran over him.”

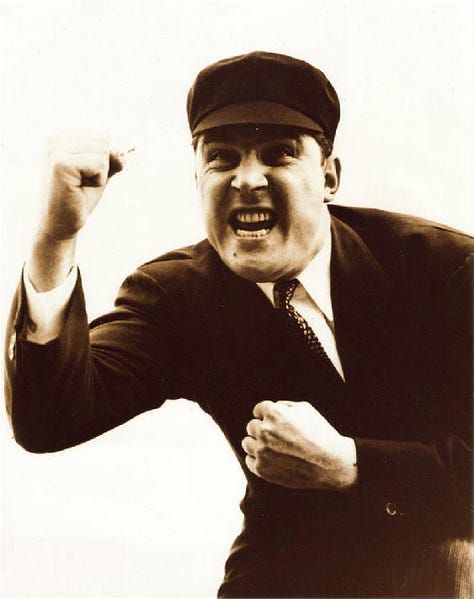

Barlick was known for his vocal stylings. His deep bass voice turned ball and strike calls into mini-opera pieces, as chronicled by a writer in 1951:

Barlick dismisses a ball with a disdainful “baouw-w-w-l-l-l-l.” And with a strike, it’s a Hollywood production. He turns an abrupt right face, throws out his right arm as if he were stabbing at a vanishing cafeteria bun, and howls “strooooooowwwwwwk!” In the face of this awesome suffering, even the batter, who didn’t swing, feels a bit better.

Crowds often picked up Barlick’s mannerisms by the seventh inning or so, and he’d finish many games backed by a choir of hundreds of impressionists.

Ballanfant was a smaller man with a much more visual style. From the same 1951 review:

Lee’s particular forte is the gesture of the hand as he calls a strike. He does it as if he were playing yo-yo.

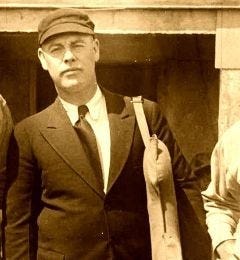

The third umpire, George Barr, had been on the field since 1931. It may be cliche to say someone “wrote the book” on a subject, but we can safely say this of Barr, who opened the first umpire training school in 1935 and wrote Baseball Umpiring—the first professional umpire training manual—in 1952. He would retire at the end of the 1949 season—that’s probably just a coincidence.

Each of the three men called a Hall of Fame wing’s-worth of baseball in their careers, including several Project 3.18 moments. Lee Ballanfant worked the 1937 forfeit at the Baker Bowl, when the Phillies stalled themselves into oblivion, and Barr would soon eject Connie Ryan for wearing a raincoat up to bat on a wet day in September.

But in middle of the 1949 season, the three were mostly known for what they had done to poor Andy Pafko.

On April 30, the “Caller B’s”1 worked a game in Chicago that ended in heartbreaking controversy. In the top of the ninth inning, the Cubs led, 3-2, with two outs. St. Louis had a runner on first when their first baseman, Glenn Nelson, laced a tailing line drive into left-center field. The Cubs’ center fielder, Andy Pafko, had been shaded the wrong way, but he raced to his right and at the last minute managed a backhand catch just a few inches from the ground, an all-or-nothing effort that sent him tumbling end over end, the ball clutched inside his glove.

At second base, Al Barlick spread his hands, palms down. He believed the ball had touched the ground before Pafko gathered it up, making it a “trap” rather than a fair catch. But Pafko didn’t see Barlick’s call—he was in mid-somersault and in his mind, he’d just made the final out of the game, so there was no rush to recover. He sat up, holding his glove over his head in triumph. Meanwhile, the Cardinals’ third base coach waved madly and the runners scurried around the bases.

“I caught the ball,” Pafko said a few days later. “The game’s over, we’ve won, 3-2. I’m feeling dizzy, but good. Then somebody yells, ‘Throw the ball! Throw the ball!’ What do I want to throw the ball for? I caught it, it’s mine. I look in and everybody’s running. So I jump up and show ‘em the ball, but they keep running and yelling, ‘Throw the ball.’ So I throw the ball—too late.”

Pafko ran in to argue with Barlick, keeping the ball in his glove, as if this proved he’d made a clean catch. Only when he reached the infield did he finally realize that his evidence was still in play. He fired a throw to home. It bounced off Nelson’s shoulder as he slid in with a 2-run inside-the-park home run that gave St. Louis the lead.

The Cubs’ manager and bench mob joined Pafko in an argument with “Bellowing Al Barlick,” who had, with a wave of his hand, reduced Pafko from game-winner to goat. Barlick was steadfast, “his head-wagging firm,” and appeals to Ballanfant and Barr went nowhere. The game was delayed for ten minutes while the crowd threw seat cushions, confetti, and a medley of fruit and vegetables on the field. The fans eventually ran out of leftovers and watched the Cubs go quietly in the bottom of the ninth.

Three days later, now in Boston, the Cubs were still talking about it, with the Braves’ players and the press. It was an outrageous call by Barlick, they said, alleging he failed to hustle to get a good view, called the play too quickly, and failed to ask his colleagues for a second opinion, which was as close as baseball got to replay for nearly 150 years.

Chicago Outfielder Harry Walker was quoted complaining about the disputed “trap” call, making comments the Cubs were no doubt repeating all over the league:

The umpires are so busy making all those fancy motions of theirs that they don’t see the plays anymore.

The August 21 doubleheader began nicely for the Philadelphia fans. Their ace, Ken Heintzelman, was dominant in the opener, pitching a five-hit shutout while the offense tacked on a run here and there, compiling a 4-0 victory in just over two hours. It was the Phillies’ fifth straight win.

There was some early evidence that the day’s crowd was lively. The Giants’ pitcher, Sheldon Jones, threw an up-and-inside pitch to the Phillies’ catcher, Andy Seminick, hitting him on the cheek. Luckily, Seminick was only grazed, but he was visibly angry with Jones and the fans took his lead and “acted up vocally.”

Much was getting away from the Giants at this moment. They had now lost five straight, culminating in the trade of All-Star first baseman Johnny Mize to the rival Yankees. A fill-in cast was now responsible for first base, and in the second game, that job would go to a part-time infielder named Joe Lafata.

New York’s odds were better in the second game, when they’d face a fill-in guy, albeit one with an excellent resume. Lynwood Rowe, better known as “Schoolboy,” had been a pitching force in the late 1930s, helping the Tigers win a World Series, but his glory days were long-past. Now 39, Rowe was used mostly for mop-up work; he got just six starts that season, but this happened to be one of them.

The Phillies began the scoring with solo home runs in the third and fifth innings, while Rowe gave up only two hits in the same span, and both runners were eliminated by subsequent double-plays. But the Giants wore Rowe down, tying the score, 2-2, in the seventh after a wild pitch and an error by the Phillies’ third baseman, Willie Jones. New York pulled ahead with another run in the eighth, but Rowe was still pitching in the top of the ninth, when the Giants threatened to add on again. The leadoff batter, Willard Marshall, singled and broke for second, reaching third when the ball got away from the Giants as they tried to catch him in the act. Rowe got the next batter to strike out, bringing up Joe Lafata in a moment where New York fans would have much preferred Johnny Mize.

Showing up his doubters, Lafata hit a low line drive into center field. Richie Ashburn raced in to catch it and throw in to keep Marshall at third. In his haste, Ashburn stumbled at the very last second, making a somersault on the grass just as he appeared to catch the ball, no more than eight inches off the ground, just above his shoes.

Is any of this sounding familiar?

Meanwhile, umpire George Barr was racing towards second base to be in position to make the call. Umpire crews would get a dedicated second-base official in just a few years’ time, but in 1949 the line umpires still had to cover half the park each.

Ashburn’s chase had taken him closer to left field, where Ballanfant would have been the one to make the call. Ballanfant may have had a better look, but Barr was resolved to do the honors as the play had started in his territory.

Ashburn popped back to his feet, the white ball peeking out of his glove hand. George Barr threw his hands away from his body, palms-down. Another “trap.” Willard Marshall scurried home, extending the Giants’ lead, 4-2.

Seeing Barr’s ruling, Ashburn threw his glove to the ground in frustration and raced in to have a word with the umpire.

“Richie came in screaming,” Granny Hamner, the Phillies’ shortstop, said. “He said he made the catch, I say he made the catch—everybody on the Phils says he made the catch. Barr still said no.”

“Ashburn never caught that ball,” Barr said. “Of course, that’s the way I saw it. It’s a matter of judgment and I guess I’m entitled to my decision.”

Schoolboy Rowe and the Phillies’ manager, Eddie Sawyer, joined the argument. Rowe added a wrinkle, claiming he’d been watching Lee Ballanfant on the other side of the park, and seen him signal a fair catch.

Barr made one more forceful dismissal of Philadelphia’s pleas, then turned his back on what was a growing crowd of Phillies—six players and the manager.

“Well, everybody screamed one more time and then we gave up,” Hamner said. “Sawyer headed back for the bench.”

Once again, the fans in the seats were eager to follow the Phillies’ emotional cues, and this time, they revolted.

It started in left field and soon spread around the outfield bleachers and through the grandstands. Boos and hisses erupted, and people “threw everything loose.” Mere seconds after Barr’s ruling, the field was unplayable with debris. One account says a number of fans “left the stands and went out on the playing field,” but mostly they let their trash do the talking.

“That’s when the pop bottles and other stuff began flying,” Hamner said. “On their way back to the outfield, Del Ennis and Richie Ashburn were almost hit.”

Under surprising friendly fire, Ashburn and Ennis soon retreated to the line where the infield and outfield met. The infielders drew closer to the pitcher’s mound, where the three umpires stood ominously, consulting their pocket watches.

Shirtless groundskeepers dodged more trash as they tried to clear the park. The crowd kept at it, “littering the field with glassware, tin cans, assorted fruits and vegetables, all by way of offering on-the-spot criticism of the wisdom, judgment, vision, and ancestry of umpire George Barr.”

When it became clear this was a full-on tantrum, the players made their way into the dugouts. Barlick called out to Eddie Sawyer, warning him that a forfeit was coming, but the manager held up his hands: “What can I do about it?”

The public address announcer made a warning, announcing the game would be lost if the fans did not cease. The admonition was booed down, but the barrage slackened. The park attendants cleaning up the outfield debris were joined by a few players from the Phillies’ bullpen, and the bleacher crowds let them work.

After ten minutes, Barlick and the other umpires motioned for the game to resume. Schoolboy Rowe came back out to the mound and warmed up. The next batter, Bill Rigney, stepped to the plate. The three umpires left the safety of the center of the diamond and resumed their positions on the lines, much closer to the low grandstand walls.

Their targets now in range, the wily crowd was about to spring a trap of its own.

In the conclusion we’ll spotlight some hard-headed Philly fans, quote a little E.L. Thayer, and marvel at the hard skin of umpires.

On February 24: “‘The Era of Bad Manners’”

This footnote serves to document that we just came up with “Caller B’s” and are extremely pleased about it.

Cool piece, Paul - I see Al Barlick retired in 1971, which is why I actually remember him umpiring.

Hahaha, Paul, your “Caller B’s” made me think of Bonilla, Bonds, and Bream, which I think was your intent! Looking forward to part 2 next week. Meg