In One Boat - Part 1 of 2

In 1937, one of the worst floods in modern American history left Cincinnati’s Crosley Field under 20 feet of water.

On January 21, 1937, with real baseball still three months away, The Sporting News was in full “offseason” mode, checking and re-checking the hot stove and (why not?) profiling the major leagues’ groundskeepers.

In Cincinnati, Ohio, three generations of Schwabs tended to the baseball grounds. The line began in 1894, when John Schwab became the groundskeeper (or superintendent) of League Park, a wooden bandbox built at the corner of Findlay Street and Western Avenue in the city’s West End. After League Park burned down, John contributed to its resurrection as a neoclassical fever-dream, the Palace of the Fans, which (re)opened in 1902.

In 1903, John retired, and his son, Mathias, took over. Mathias—who went by Matty—grew up in and around Cincinnati baseball, helping his father at work and becoming a serviceable player. He was good enough to spend two seasons in minor league ball, pitching for a club in Vicksburg, Mississippi in 1901 and 1902, but his athletic talent crested there. When his father retired in 1903, the family business called Matty home.

Nine years into Matty Schwab’s tenure, the Reds upgraded again, replacing their crumbling Palace with a state-of-the-art facility, initially called Redland Field (renamed Crosley Field when a local retail magnate, Powel Crosley Jr., acquired the team in 1934). By 1937, two of Matty’s brothers and his son, Matthew, were a part of his grounds crew.

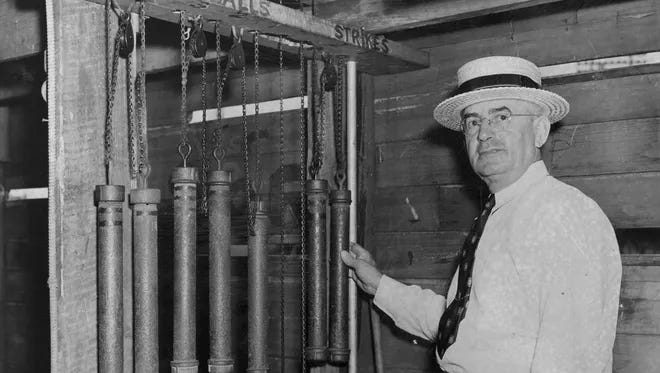

He may not have been a great pitcher, but Matty Schwab was an All-Star groundskeeper. His infield played butter-smooth. His tripartite lawn of blue grass, fescue, and something called “Red Top” withstood the extremes of the Midwestern seasons, from freezing to broiling and back. Schwab half-invented and installed baseball’s first “pop-up” sprinkler system in the infield and created the first mechanical scoreboard capable of updating game information in real-time.

“[Schwab] works long hours, winter and summer, because keeping a ballpark in trim is not a six-month job, but a 12-month occupation.”

The magazine profile emphasized that groundskeeping was no garden hobby. The best, like Schwab, were part horticulturalist, part engineer, part geologist, and part plumber, and their season never ended.

The same day that Schwab’s profile reached newsstands, two inches of rain fell on his grounds in Cincinnati. Rain totals were headline news in January 1937, the wettest single month in the city’s history. By January 21, 8-10 inches had already fallen as one storm after another pushed the entire Ohio River valley region toward a precipice.

Spring floods were a regular part of life along the river. The Ohio was usually 40 feet deep at Cincinnati, and if the river reached 52 feet deep, it escaped its banks in a flood. There had been several dozen flood events since the city’s founding, and while most were under ten feet, there had been some Real Doozies, like the record-setting 1884 flood in which the Ohio rose to 71 feet high, almost 20 feet above its channel.

It took far less than that to inundate Crosley Field. The park sat in a low-lying area of the city, 1.5 miles from the river but just 2000 feet from the Mill Creek, a large tributary. When the Ohio rose, creating powerful currents, slower-moving water from the creek had nowhere to go, and it would back up and spill into the West End in a flanking attack.

Crosley was built from concrete and steel, designed to let flood waters come and go with minimal drama. Finished in 1912, the park was tested almost immediately by the Real Doozy of 1913. That flood hit other parts of the region hard, but Cincinnati took only a glancing blow; many residents’ biggest concern was the potential of disruption to the Reds’ home opener, eight days away. Despite significant water intrusion into the ballpark, superintendent Matty Schwab got everything cleaned up and a happy crowd watched their team lose to the Pirates, 9-2.

In 1937, the unseasonably warm January produced steady, heavy rains, and the Ohio River channel quickly filled. On January 18, it had reached flood-stage, spilling water into the city’s lower-lying areas.

January 18 was also the day the first water appeared at Crosley Field. It came—as it always did—through the toilets in the dugouts, the lowest pipelines in the park. Schwab and his small staff busied themselves moving anything that could be carried up into the higher reaches of the grandstands and the second- and third-floor office areas.

If the rains had stopped after January 21, the park would likely have remained above water, even though other parts of the city were already flooding. But the next day a combination of rain, snow, and sleet pushed the water past the 1913 mark. The Mill Creek backed up and made for the ballpark’s main gates.

By January 22, water covered the entire field, all the box seats, and the base of the grandstand. Schwab and the crew began moving around via boat. It is likely that they began living in the park, avoiding what had become a difficult commute into the office:

The river was now 73 feet deep—more than 20 feet above flood-stage. Parts of the city were hard-hit, but the lights and the faucets still worked. 74 feet was a magic number for emergency planners: water that high would flood the pumping stations that provided the city’s drinking water and shut them down. With strict rationing, the city’s water reservoirs held 10 days-worth of useful water.

January 23 brought a reprieve. Colder temperatures produced six inches of snow, which added far less water volume. The sun broke through in the afternoon and the river barely rose. It was a day of precarious hope.

Then came January 24, a day remembered as “Black Sunday.” In the Cincinnati Enquirer, a writer named Alfred Segal gave a narrative account of what happened.

The day started warm, he wrote, with water dripping from buildings under clear skies. But a drizzle began at 11:00 am and soon strengthened into a fresh and back-breaking downpour. “The skies opened as if they hadn’t given everything they had the week before.”

2.3 more inches of rain fell. The warmer water also melted the snow from the previous day. The river reached 74 feet that afternoon, and the sandbagged pumping stations stopped as flood water poured in through their windows.

The city manager, Clarence Dykstra, assumed the role of “Disaster Administrator” and gained dictatorial powers, enacting strict conservation measures of electricity and water, closing all non-essential businesses, and banning the sale of hard liquor. Beer was not banned—days were coming when beer and soda would be the only things some people could get to drink. Coast Guard cutters shipped in on trains were launched into the riverfront Bottoms district, patrolling flooded areas, their New Jersey crews instructed to “vigorously” respond to any looting.

Segal wrote of the way the extent of the disaster gradually dawned on people via their radios. Regular programming was increasingly interrupted by breathless instructions:

“Don’t use your telephone… don’t come downtown… don’t use electricity too much…. Fill up your bathtub—fill every container…”

Outside, he saw telltale signs of panic:

One saw the neighbors coming home with big baskets loaded with food supplies. The grocery, they said, was crowded with troubled people who hoped there was enough in the store to go around.

The next grim benchmark was 75 feet, at which point the city’s power plants would flood. The river was 74.7 feet deep by dusk. “A power loss,” Segal wrote, “seemed the most terrible thing of all. Nobody had thought so much about light before…light was something always to be had by the touch of a finger on a button.”

Already ordered to limit electricity to one light per home, residents all over the city watched those lonely bulbs, waiting. Across the city’s seven hills, many people were safe from flooding, but at 75 feet, the disaster would reach into the highest, driest homes.

“All of a sudden,” Segal wrote, “all the 450,000 inhabitants of the city were like people in one boat, helpless.”

The lights went out near midnight. The river, still rising, passed 77 feet.

In the city’s Mill Creek district, not far from Crosley Field, the slow, brawny shove of the creek reached the area’s industrial storage yards, casually toppling eight 50,000-barrel tanks and pouring a million gallons of gasoline into the flooded streets. On the evening of January 24, a sparking power line fell into an oily patch of water and started the Mill Creek fire.

With no water in the pipes, 35 city fire companies and volunteers from nearby communities fought the fire with the flood, using every foot of hose to reach standing water sources sometimes a whole block away. Pressure was provided by five portable pumping machines. The fire burned for the better part of a day, doing an estimated $1.5 to $2 million in damage, including the destruction of a warehouse and refrigerator plant owned by the Reds’ owner, Powel Crosley, but the fire crews kept it under control and eventually turned the tide.

Fire was a paradoxical terror in this waterlogged world. Dykstra implemented an outdoor smoking ban, and National Guard members were put in boats and sent out with orders to arrest anyone seen with a lit cigarette, which—if dropped in the wrong place—could take out a quarter of the city. Any fire away from the waters could be just as large a problem. The city’s fire chief warned citizens to place any lit candles in a container of water at least two inches deep.

A number of individual homes were lost to fire, but the Mill Creek fire was the only major blaze during the crisis. It caused extensive damage to the district, but only a few injuries and no deaths.

City phone service (where available) had been restricted to emergencies, but this was a subjective term. One resident called into the fire department’s switchboard to ask about the fate of two prominent characters from a local radio show. Other calls ran the gamut:

I have 150 pounds of fish, what am I supposed to do with them?

Can I break into a store to get coffee for the firemen?

Would my garden hose help?

One of the firefighters working virtually around the clock was a veteran named Albert Schott. Probably in his late 50s, Schott had been a Cincinnati firefighter for many years. He and his wife lived either on the city’s east side or in a suburb just next door, along with their son (Albert’s stepson) Eugene, who pitched for the Cincinnati Reds.

Gene Schott, 23, was a right-handed pitcher and the team’s only hometown player. Earlier in the offseason there had been rumors that Schott would be traded in a package to bring Dizzy Dean to Cincinnati, but nothing came together and he signed a two-year contract instead. His near-future secure, Schott hung around town that winter, conducting occasional promotional appearances to make some extra money. One of these appearances would become so famous that we’re writing about it 88 years later.

The Ohio was still rising on January 25, as was the Mississippi it emptied into; flood warnings were in effect from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Cairo, Illinois, all the way down to New Orleans.

In Cincinnati, potable water had become the most pressing concern. By January 27 the city had 80 million gallons left to sustain a population that normally used 60 million gallons a day. Engineers worked around the clock to establish a connection to the nearby suburb of Norwood, which got its supply from an underground aquifer. Water was also being shipped from Columbus, Chicago, and other cities via tank cars, but the flood had brought most of the Midwestern rail network to a standstill. In the meantime, restaurants and other vendors advertised in the newspapers: “Plenty of Coca-Cola available here for drinking purposes!”

Rationing measures tightened every day. From four hours of water service to two hours and then one. Residents were instructed to boil everything for ten minutes—the on-and-off procedures had stirred “hazardous sediments” that normally lay dormant on the bottom of the pipes.

Without pumps, the reservoir water could only reach low-lying areas. While people up on the seven hills were safe from floodwaters, they were now in danger from having no water at all, forced to climb up and down to supply points carrying cans, jugs, and bottles (non-emergency automobiles were banned). The more water people found below, the harder their climb back up became. In dry areas, portable toilets were built on top of open sewer manholes.

The city’s animal residents needed water, too, and the staff of the Cincinnati Zoo were steadily draining the relatively-untainted water from the moat surrounding the zoo’s Monkey Island enclosure. The (boiled) moat water kept the rest of the animals going. Still, the writer observed, “these are great days to be a camel.” It was also great to be a monkey—with the moat down they were able to escape and explore the rest of the zoo.

January 26 was probably the worst day. 500,000 people were homeless across 11 states, and the small death toll was beginning to climb. Many communities in Kentucky had been completely inundated and cut off. In Ohio, 45 of 350 square miles in Hamilton County were flooded, including 11 of 72 square miles inside Cincinnati.

Blanketed in thick, noxious-looking mists, the yellow waters of the Ohio lapped at the city, including some spots usually a mile away from the water’s edge, and basements were full much further away than that. At night Cincinnati became “a city in wartime, dark and deserted.”

Traversing the waters could be dangerous. Near the river channel, the current pushed water downstream at a million cubic feet a second, and debris raced along, slamming and tearing as it went. In some places the water was so high that telephone poles had become underwater hazards. The power plants were offline, but some electricity was still coming in from nearby Dayton, Ohio, supplying hospitals, shelters, and other critical facilities via lines strung across the city. In some places the water was so high that people sitting in boats risked brushing against these still-live wires.

A flotilla of small boats searched this wasteland for stranded people. The rescuers were a motley crew, including 1,500 national guardsmen and troops of local Boy Scouts, earning a once-in-200-years merit badge.

Two such pre-teens rescued a surprised but grateful young woman and her mother from their attic. Safe in a shelter, she recalled “an endless night” watching the water reach her stoop, her front porch, the doorway, the living room, “licking at the stair and snaking to the second floor.” The next few nights on a straw mat in a packed gymnasium weren’t great, either, but she was alive.

“It’s one of those things,” she said. “But, I can take it.”

On January 27, the river topped out at 79.9 feet high. Meteorologists warned it would take the river 10-12 days drop down to 60 feet, a level where “it was believed power could be restored and pumps turned back on.” A city official warned, “we cannot expect resumption of anything like normal activity in Cincinnati until the river reaches that point.”

While normal activity was still far off, people wanted to get out, and the day offered clear skies and sunshine, revealing “a city of the unwashed, unshaven, and idle.”

Among those idled was the only other Reds player in town, left-handed pitcher Lee Grissom. Like nearly all of his teammates, Grissom, 29, left Cincinnati after the season, taking opportunities to play in warmer climes or work a second job. At some point that winter, he began weakening and losing weight, and was belatedly found to be “suffering from an infection.” When he finally sought treatment, Grissom went to someone he described as “an Indian doctor,” who treated him with poultices, or, as Grissom said, “he put leaves on me.” Whatever the leaves were, he was not cured, and he finally made the Reds aware of his illness.

The team was unhappy with Grissom’s handling of the situation, so unhappy that they ordered him to return from his winter quarters in California and enter a hospital in Cincinnati, where his care could be managed by the team doctor. He arrived back in the tri-state area in early January. After his release from the hospital, Grissom had to remain in the area for outpatient care. He was staying in an apartment in Kentucky and commuted in for his appointments. During one such appointment Cincinnati abruptly shut down nearly all bridges over the river and he was stuck.

Idled in Cincinnati, Grissom probably wasn’t doing much—he was out of the woods, but still recovering and not strong enough to help with flood relief efforts. On January 27, someone from the Reds got in touch. Could he make his way down to Crosley Field? Gene Schott received a similar summons.

The two men were being recruited into a little stunt, something to “give the flood news a different touch,” and maybe bring the team a little publicity.

After weeks of hunkering down, it was time for Cincinnati to start reclaiming what the water had taken, and the Reds (all two of them) could set an example:

In the conclusion, we’ll tell you how this shot came together (including the unexpectedly “baseball-famous” photographer) and watch the unsinkable Matty Schwab re-float his ballpark.

You dig up, Paul, the most amazing things. I lived in and around Cincinnati from my mid-20s to mid-30s, about half of that time in a suburb very near Norwood, the other half in Northern Kentucky, which is separated from downtown Cincinnati by the Ohio River. I went to hundreds of games at Riverfront Stadium. My in-laws still live in the area. I know pretty well all the places in your story. And I have never heard anything about the 1937 flood affecting Cincinnati; it is a disaster I associate with Johnstown, PA, or did until right now at any rate. Thanks for bringing this history to life.

Amazing read! Thank you for the in depth research and great story telling!