Hurry Up and Wait

In 1937, with the clock running down, each teams' only hope was to play as poorly as possible.

Today we’re happy to share a fourth(ish) installment in our series on notable baseball forfeits.

A game like that is a dirty outrage on the public. Those people paid to see major league baseball. They didn’t get it in that game.

That is what Bill Klem, godfather of umpires, said after he and his fellow officials (but really just Klem) called a forfeit in the second game of a June 6, 1937 double-header. When the game was called, the score was 8-2 in favor of the visiting St. Louis team, and making it look like Cardinals were destined to win either way. In fact, the Cardinals came very close to “not winning,” as their opponents, the Philadelphia Phillies, tried to exploit a tangle of baseball and civic rules and escape a lopsided loss.

They almost made it.

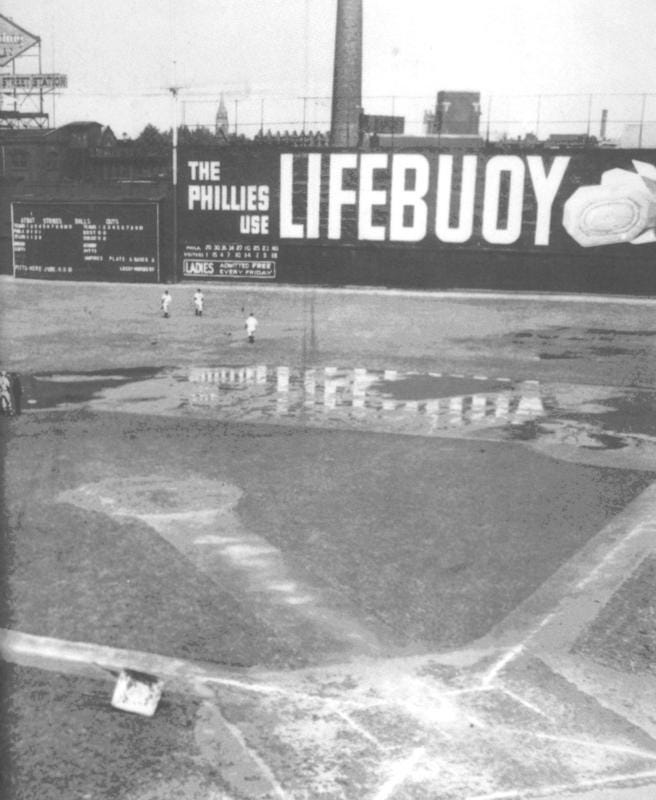

The non-game took place at the Baker Bowl, a ballpark that sportswriter Red Smith once called “the quaint little Philadelphia slum of blessed memory.” June 6 was a broiling day in Philadelphia, but the Baker Bowl was about two-thirds full, with 12,000 fans risking heat stroke to see their dead-end Phillies take on the “Gashouse Gang” Cardinals, still pennant contenders, but not the Depression-era powerhouse they had been earlier in the decade.

The afternoon’s first game was non-competitive. St. Louis recorded seventeen hits off of three different Philadelphia pitchers. The outcome was already close to decided by the third inning, when unexpected clouds blew in from the west. An inning later those clouds tore open and dumped 30 minutes of torrential rain and hail on the city below.

The teams huddled in their dugouts and made the best of things. Pitcher Dizzy Dean amused his St. Louis teammates by running around trying to catch drops from the leaking roof on his tongue. With much less cover, the people in the stands were perfectly miserable. The corrugated sheets of roofing metal only partially covered the grandstand and gave little protection from the sideways sheets of rain that mixed with dust from the field. The rain and hail pounding off the roof “sounded like a whole army of machine guns going full blast.”

On calmer days, one of the 43-year-old grandstand’s little charms was the way a light dust of corrosion would sprinkle down on fans whenever a foul ball banged off top of the roofing, but the sustained barrage of the storm “shook rust, grime, and the accumulated debris of ages out of the rafters and on to the multitude.”

The storm and the damage it caused made front page news, and one writer called it “one of the heaviest rain, wind, and hail storms ever seen1 in Philadelphia.”

When the skies cleared, the outfield and sidelines were lakes and the infield had standing water, creating trenches of sucking mud so formidable that many of the work crew trying to restore the field opted to go barefoot. They carted out dozens of wheelbarrows full of sawdust and sand, dumping the mix up and down the base paths. Even some of the visiting players were enlisted to help. Cardinals first baseman Johnny Mize took up a rake and tried to mix the sawdust in around his position.

The clean-up took twice as long as the storm. When all the work was done, there was still a pool of water around second base, and when center fielder Pepper Martin singled in the ninth inning, he lost a shoe to mud on the basepaths and had to borrow someone else’s to finish the inning.

The Cardinals beat the Phillies, 7-2. All told, the game took three hours and 45 minutes to conclude, and the humid air quickly returned from its water break, steam-cooking the fans in their grimy, soaking clothes.

After the briefest of intermissions, the teams prepared to go again. The second game got underway at 5:36 pm, but the late start was going to be a problem in Philadelphia, because June 6 was a Sunday.

Laws restricting what people can do with their Sundays have existed in America going all the way back to the Jamestown colony. Initially, such laws helped working people by ensuring they would get at least one day off a week, but as time went by the terms of use grew and grew.

In Pennsylvania, the terms were set by the Quakers, members of a Protestant sect that began in England in the 1600s, many of whom later emigrated to an American colony founded by one of their own, William Penn. In Penn’s religiously-minded community, the Sunday laws quite granular, regulating what did and did not count as “rest” on the Sabbath Day.

Such laws became broadly known as “blue laws” for reasons that are today unclear. The first set was enacted in 1682 and sought to “restrain disorderly spirits and dissipation” in the colony. When the state of Pennsylvania’s laws were codified in 1794, Sunday rules prohibiting hunting, going to the theater, and the sale of alcohol were among them. The rules were periodically expanded as Pennsylvanians found new ways to have fun. Later revisions would prohibit organized team sports (and buying a car, for some reason).

Pennsylvania did not amend its original blue laws to allow Sunday sports until 1933, when a limited afternoon window for baseball and football2 went into effect, and this remained the way of things four years later. On a Philadelphia Sunday in 1937, baseball actually did have a clock, and it ran out at 6:59 pm.

Two games in an afternoon could be done in those days, but the weather delay made the Sunday law a real problem, because there was no “pausing” a game in that era. Baseball’s “no contest” rules said that teams had to play five innings to complete an official game. Anything less, and the game would have to be replayed in full another time.

On paper, five innings seemed doable, even in the 83 minutes remaining before the baseball curfew. The day before, these same two teams finished an entire nine-inning game in just 109 minutes.

But the first inning “gave early promise of constituting intolerable cruelty” to anyone with dinner plans. The Cardinals spent a long 25 minutes knocking pitcher Hugh Mulcahy around for five runs, three on a home run struck by St. Louis’ star outfielder, Joe Medwick.

The Phillies hit back, scoring two runs in their half-inning and leaving the bases loaded, but all in all, one impatient wrote, the whole effort “had no purpose save to delay the game.” By the end of the first inning it was several minutes past six o’clock.

A large early lead raised the specter of the “no contest rule.” If St. Louis made it through five innings, they knew they’d have a win. But anything less than five innings and the game’s progress would be erased, including Philadelphia’s deficit. When the two teams started over, it would be 0-0 in the top of the first.

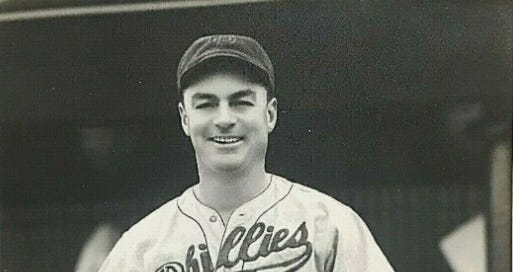

To the layman’s eye, the second and third innings proceeded in proper order, but later, the Phillies’ player-manager, Jimmie Wilson, claimed that the Cardinals had started the trouble in the second inning when they began rushing through their at-bats. “So when we saw that,” the manager said, “we started taking our time. But I won’t admit we were stalling.” Wilson insisted “every move I made was legitimate,” but you’ll get to be the judge of that.

If Wilson was telling the truth, the Cardinals’ hurried at-bats were subtle enough to be overlooked by the umpire crew, composed of Lee Ballanfant at first, Ziggy Sears behind home plate (and notionally in charge), and Bill Klem behind second.

When we last saw Klem, he was a young umpire working solo in 1907, dodging snowballs at the Polo Grounds. Three decades later, he was largely the same stern taskmaster, but he was also a living legend.

Lee Ballanfant got to the majors in 1936 and worked with Klem for five years. “Klem was the king of umpires,” he told historian Larry Gerlach. “He was a czar on that ball field. You needed a czar in those days.” You’ll get to be the judge of that, too.

On the field with two junior attendants, the opinion of Czar William I was the only one that mattered, and he checked his pocket watch with increasing frequency as the day’s window for baseball (and football and polo) inched shut.

With one out in the fourth inning, Jimmie Wilson made his first mound visit of the game, to converse with Hugh Mulcahy, the pitcher. Wilson departed as the Cardinals’ batter, center fielder Pepper Martin stepped in. Mulcahy uncorked a pitch so high and wild it crashed into the front of the grandstands.

Up in the press section, a Philadelphia writer nudged a colleague from St. Louis. “There it starts,” he said. “The big stall has begun.”

6:31 pm

Second mound visit: Wilson went back out to the mound, this time followed by suspicious umpires. The manager explained that his pitcher had a sore finger, but he would try to push through. Pepper Martin eventually walked.

Third mound visit: Well, that was quick. Wilson came back out to change pitchers, calling for Claude Passeau. Except Passeau didn’t get the message; he seemed to be having trouble hearing. He continued warming up in the bullpen in deep right until umpire Ziggy Sears walked all the way out to tell him to come to the mound if he planned to pitch.

Realizing that the Phillies planned to run out the clock, the Cardinals began barking at the umpires. Meanwhile, Passeau’s temporary deafness clued the crowd in, and howls of glee broke out.

6:36 pm

Passeau declined to throw strikes, but the St. Louis batter was determined to record a quick out and “found a pitch within reach.” He hit it to the Phillies’ left fielder, who made the catch “with the stands roaring for him to drop it.” Two outs.

On the bases, Pepper Martin broke for second, hoping to be thrown out, but nobody threw. Wilson called for an intentional walk of the next batter, “who got four balls he could not have reached with a fishing pole.”

6:40 pm

Then came slugging Joe Medwick, who hit a ground ball to shortstop, normally a sure out. Norris, the Philadelphia shortstop, was within a step of the ball but didn’t move his legs, only waving his arm at the passing ball “as though startled by an apparition.” As the ball rolled into the outfield, Medwick tried to be thrown out at second base, but the outfielder dropped the ball as he tried to pick it up. Medwick was jogging so slowly he still might have been thrown out, but instead of tagging him, the second baseman, Del Young, simply threw the ball back to the pitcher. This was a particularly egregious mistake, so Wilson got asked about it afterward. “Why, Del didn’t see him,” Wilson said.

Safe at second and having driven in another run for his team, Medwick was furious, shouting at the umpires and forcefully making the case that he should be out. It was, one writer observed, “a double that had been forced upon a man against his will.”

Fourth mound visit: Wilson chatted briefly with Passeau, who walked the next batter, Johnny Mize. The next batter hit a fly ball so straightforward that the outfielder’s dignity compelled him to catch it and record a third out. It had taken Philadelphia an impressive 17 minutes to make two outs.

Meanwhile, the crowd was having a ball, rooting for the Phillies’ last-ditch efforts to escape defeat. Wilson was cheered each time he stepped out of the dugout and people shouted advice on how to waste more time.

6:48 pm (bottom of the fourth)

To waste time on offense, the Phillies actually needed to get on base, but this was not their forte as a club. All three hitters inexplicably swung away and hit three easy fly balls to Pepper Martin in center field.

6:50 pm (top of the fifth)

Shortstop Leo Durocher was the first Cardinal to bat. His first swing actually earned a rebuke from Sears, the home plate umpire. “I saw Durocher swing at a wild pitch,” Sears said, “and so I quickly warned him that he had better not try that again.”

Durocher grounded the next pitch to Norris, the shortstop, who threw the ball into the Phillies dugout. “In my estimation, he deliberately threw past first to prolong the game,” Sears said.

The next batter hit a pop fly to an outfielder “who seemed to make the catch against his will, with the stands still shouting for muffs, fumbles, and related shenanigans.”

Then came Jess Haines, the St. Louis pitcher. Jimmie Wilson signaled Passeau to walk him anyway. Haines stewed through three outside pitches and then revolted, swinging at a ball “two feet wide” of home plate. Somehow he made contact and hit an easy ground ball, but it mysteriously disappeared between the infielders, and Haines ended up on base.

Fifth mound visit: Wilson came out “to argue with the umpires,” though about what is unclear. Sears and Klem ordered him away, but he reemerged moments later to make another pitching change.

Sixth mound visit: Wilson called for another pitcher, Syl Johnson, a noted control expert who previously pitched for St. Louis. Johnson was so slow coming to the mound that Sears and Klem cut his allotment of warm-up pitches by half.

The farce was reaching a crescendo now. With expert control, Johnson bounced a ball in front of Pepper Martin, but Martin swung anyway. The next pitch went “seven feet over his head” but Martin swung again.

Bill Klem was reported to be “frothing at the mouth like a mad dog, running from player to player, shanking his finger at their noses, and spouting words of liquid fire.” Czar William moved behind the mound and told Johnson to find the plate or the game would be forfeited.

Another wide pitch, Martin didn’t swing. And one last pitch so wild the catcher never got a hand on it. Martin swung, the ball rolled to the backstop, and Durocher walked in from third, scoring a final run.

Klem had seen enough. He summoned Ziggy Sears to the mound and “advised him” to forfeit the game.

6:55 pm

Sears turned to address the grandstand and shouted: “This game is forfeited to St. Louis by a score of 9 to 0.” While such debacles had once been commonplace in baseball, this was the first forfeited game in 12 years.

Sears’ proclamation elicited boos, hisses, and hoots from the crowd. “We umpires didn’t act hastily,” the umpire said after. “We gave the Phils plenty of time, but they insisted on stalling so flagrantly that we were forced to give the game to the Cardinals.”

Seventh mound visit (do we count this one?): Wilson emerged one final time to argue the forfeit, “looking stunned.”

The forfeit announcement was repeated over the public address system (which at the Baker Bowl was still just a guy with a large conical megaphone). Some displeased fans threw their seat cushions and score cards at the umpires who’d spoiled the game. Some of the Cardinals emerged from their dugout to protect the umpires as glass soda bottles began zipping through the air. “It was strange,” one writer said, “to see the roughhouse Cardinals in the role of umpire protectors, and beneficiaries of umpires’ decisions.”

One gets the sense that if Klem could have given both teams a loss, he would have.

“The St. Louis team did not help out any,” Klem said. According to the reporter on the scene, he actually “bellowed like an enraged bull.” The Cardinals “should have let us handle it,” the umpire said/bellowed, before condemning the whole affair as a “dirty outrage.”

The Cardinals had rushed nearly as much as the Phillies stalled, but calling a forfeit meant assigning a winner, and there really no good options.

The National League president, Ford Frick, fined Jimmie Wilson $100, a penalty assigned to any manager whose team forfeited. Frick said he didn’t feel like that was enough of a punishment for Wilson’s “dilatory tactics,” and he was looking for other charges to file. Wilson had the right to appeal the fine and argue he hadn’t deliberately stalled the game, but that would bring the matter to the commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, and “Wilson would have to be a magician, a hypnotist, or a remarkable spellbinder to prove that case.” The manager chose to pay his fine.

It would be decades before Sunday night baseball came to Philadelphia. In 1972, the state of Pennsylvania rewrote its entire criminal code, but left the remaining “blue laws” on the books. But in 1978 the state supreme court ruled that the blue laws were unconstitutional and essentially unenforceable, and that was as green a light as Pennsylvania would ever give to nighttime events on Sundays.

Legislators have made periodic attempts to repeal the blue laws and clean out the state’s statutory closet, as recently as 2020 and 2022, but these efforts have all come up inexplicably short, it being apparently easier to just ignore them. You still can’t buy a car3 on a Sunday, though; that one was apparently a dealbreaker for William Penn.

We’ll be back next week with a story we teased in our 1983 White Sox piece a few months ago.

On the night the 1959 Go-Go White Sox won the pennant, an overenthusiastic Chicago official decided to set off the air raid sirens to mark the occasion. In addition to being just a ridiculous story, the incident inadvertently revealed how unprepared many Americans were for a real emergency and led to calls for national reforms.

On December 16: “The Duck-and-Cover Pennant”

Storms at the Baker Bowl brought a multitude of dangers. In 1927, fans seeking shelter from rain crowded into section of the lower deck with rotting support beams, triggering a collapse and a panicked stampede.

Sunday polo and fishing were also green-lit in the 1933 legislation. Professional basketball did not yet exist and the city’s hockey team folded in 1931, so neither sport was included in the exceptions and and could not be legally played on Sundays in Philadelphia (at all) until 1957!

Buying a vehicle on Sundays remains illegal in 17 states!

The events related herein are worthy of epic status. And you’re clearly the best man for the job. Don’t forget to drop Hollywood a line. It’s time for an updated tribute to the Golden Age of American Sport, now that we’ve had 40 years to watch re-runs of “The Natural”.

Thanks Paul great story. You still make my Mondays worth living for.

It's still the 1800s here in Texas. I think car dealerships have an option of opening on Saturday or Sunday but not both. I'm not sure because I haven't been able to afford a car new or used in a decade. Liquor stores must close on Sundays but you can buy all the beer and wine you want. After 10:00am. Used to be noon but apparently some of our legislature wanted a day buzz. As far as that Sunday liquor ban goes, I just stock up on Saturday. The law doesn't legislate drinking on Sundays just sales. Meanwhile bars and restaurants still sell liquor on Sundays. I don't get it. 1800s Texas. Hell, I can't even figure out the Astros.