Ball Night '95: The Last Forfeit in Baseball History

Giving away baseballs worked great for the Dodgers, until the fans started giving them back.

Here at Project 3.18, we’re slowly making our way through baseball’s more notorious forfeits, but we like to hop around on the timeline. Today we’re hopping all the way to the end (?) of this inglorious baseball tradition.

In the beginning, Walter O’Malley gave Dodger fans free stuff, and Los Angelenos were happy.

Only tasteful stuff, mind you. While other, crasser franchises gave away hosiery, farm animals, and the occasional 200-pound block of ice, the Dodgers’ eminent owner gave his blessing to Bat Night, Cap Night, and Ball Night1.

In the 1960s, even this type of promotion was frowned upon by some in baseball. Yankees general manager George Weiss once scoffed at the prospect of giving away merch: “Do you think I want every kid in the city walking around in a Yankee cap?”

The first Ball Night at Dodger Stadium was held on June 28, 1968. The team had 30,000 balls and 29,602 of them were placed in the happy hands of fans aged 14 and under. The kids brought their grown-ups and the park was packed with nearly 52,000 people. The Braves’ Milt Pappas smothered the Dodgers under a four-hit shutout, but from a revenue perspective the night was a smashing success. The team brought Ball Night back in 1969 and drew 47,000 people.

In the early 1970s, the Dodgers’ embrace of giveaways made the team an unlikely force in baseball’s promotional vanguard. Marketing was a part of business, and baseball was their business. Peter O’Malley (Walter’s son; team president) had no qualms:

These promotions are not a distress sign. It’s a matter of competition. Gas stations give away a myriad of things and nobody is worried about the gas industry. However, we insist that our promotions and giveaways be identified with baseball.

And so the Dodgers held baseball-identified promotions like Nun’s Day, Boy Scouts’ Day, Dairy Night, and Post Office Night (letter carriers got in for half-price). And there was always Ball Night. In 1974 the promotion drew 53,689 people, a new record.

The giveaway craze slowed during the 1980s. Eccentric owners came and went, and teams stopped passing out sheep and underwear, but Ball Nights continued to be good business for the enduring O’Malleys. The club put nearly half a million baseballs into circulation and corporate sponsors even started paying for the balls. It was perfect—until the 1990s ruined everything.

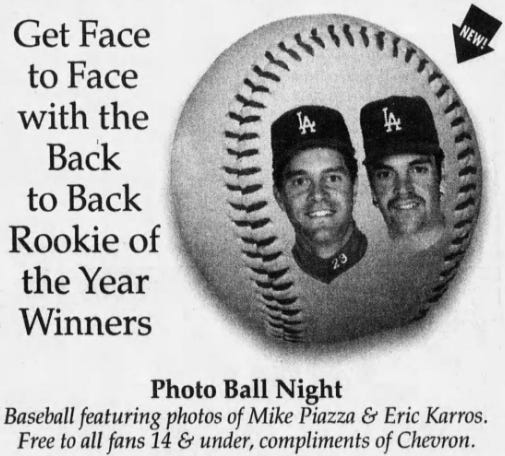

By 1994, Ball Night had become Photo Ball Night. The premise remained the same; kids got a baseball, but the balls were getting weirder:

Perhaps the Dodgers felt their old giveaway needed something. A complementary baseball wasn’t what it used to be, not with MTV and Super Nintendo and the Internet vying for kids’ free time. The modest innovation produced only a modest gate; only 34,717 people showed up for Photo Ball Night.

In the midst of a Dodger rally in the fourth, third baseman Tim Wallach was caught trying to steal third during Eric Karros’ at-bat. After Wallach was called out, some people returned their photo balls.

A few landed in left field, then some in the infield, then a few more in right. The players were confused; Karros reflexively stepped out of the batter’s box. Was it a protest? Aimed at the umpire, or the slow-footed third baseman who ran into an out? The umpires briefly cleared the field while the balls were collected. Play resumed and the game concluded without further incident, but something had changed.

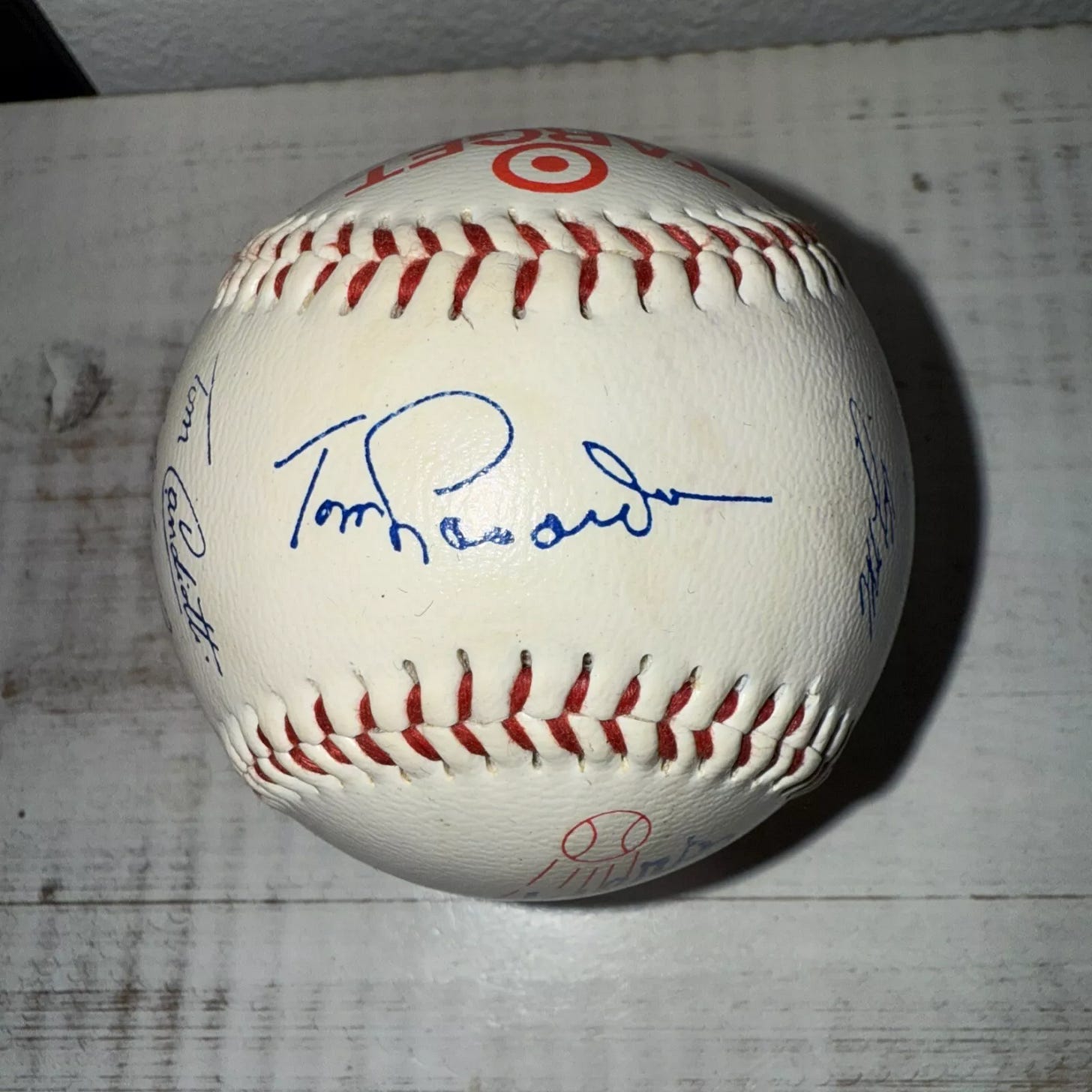

The 27th Ball Night was held on August 10, 1995. This offering was imprinted with the teams’ signatures and that of the manager, Tommy Lasorda. The balls also featured the red bullseye logo of the promotion’s sponsor—Target.

53,361 people packed Dodger Stadium on a Thursday evening to watch the Dodgers face a tail-end St. Louis Cardinals club. The giveaway ball surely didn’t hurt, but these fans were out to watch Japanese phenom Hideo Nomo pitch the real thing. As they filed in from the parking lots, 15,000 fans (aged 14 and younger) received their complementary souvenir.

The first ball was returned in the fourth inning. St. Louis first baseman Mark Sweeney hit his first major league home run and the players began trying to retrieve the ball as a memento for Sweeney, as was custom. The Dodger outfielders beseeched the fan who caught the homer to throw it back, and after some deliberation, the fan threw the ball out into right-center field.

The returned ball made its way to Eric Karros at first base. He looked at it, shook his head, and put it in his pocket. Seeing this, the Cardinals’ first base coach, José Cardenal, shouted for Karros to hand it over. Karros tossed it into the St. Louis dugout. “Bunch of idiots,” he called. “It’s the wrong ball.” In an effort to keep the real thing, the fan had thrown back one of many available decoys.

The first true salvo was fired in the seventh, with no obvious causal event. Right fielder Raúl Mondesi was batting with a 3-1 count. The Cardinals’ pitching coach, Mark Riggins, made a mound visit, and he believed this was what triggered some of the Dodger faithful. “I guess people were a little impatient out there,” Riggins said. “I came into the dugout and the next thing I knew, balls were flying all over the place.”

The umpires immediately halted the game and called the Cardinals off the field. There was a 15-minute delay while members of the grounds crew gathered up at least 100 balls scattered all over the outfield. The stands bristled with 14,900 more.

In the eighth inning, down 2-0, the Dodgers scored a run and had an opportunity to add a few more as Karros came up with two runners on base. The rally ended when the first baseman looked at a called third strike. Karros was plainly unhappy with the call but left the plate without incident. As he returned to the dugout, Tommy Lasorda told Karros the video replay showed that home plate umpire Jim Quick had blown the call. As Karros walked off the field at the end of the top of the ninth, he informed Quick of his earlier mistake. Quick threw him out, but as he had just batted and finished his defensive work, hardly anybody noticed. If they had, the game might have ended right then.

The Cardinals prepared to defend their slim lead, but it wasn’t going to be easy. “I almost got hit in the head coming out of the bullpen,” St. Louis closer Tom Henke said. “And those weren’t soft balls. The only thing worse would have been if they had given them bats.”

As John Mabry, the Cardinals’ right fielder took his place, somebody threw a ball that landed near him. “I acted like I was going to throw it into the crowd but I deked them and threw it into the bullpen,” he said. “They got mad.”

Another ball came his way. Then another, directed toward center fielder Brian Jordan. He and Mabry looked at each other and Jordan shrugged.

Raúl Mondesi led off the Dodger ninth. Facing Henke, Mondesi worked a 3-0 count. Henke’s next pitch seemed outside to Mondesi, and he took three assured steps towards first base. Big mistake. Quick called it strike one.

Henke’s next pitch was way outside, but Quick—hoping impart a valuable lesson to the young Mondesi—called it strike two. Henke tried the same spot a third time, and Mondesi had no choice but to swing. Strike three. Jim Quick was clearly waiting for what happened next. Walking out of the box, Mondesi turned his head back to gripe, and he scarcely had time to gather his thoughts before Quick ejected him.

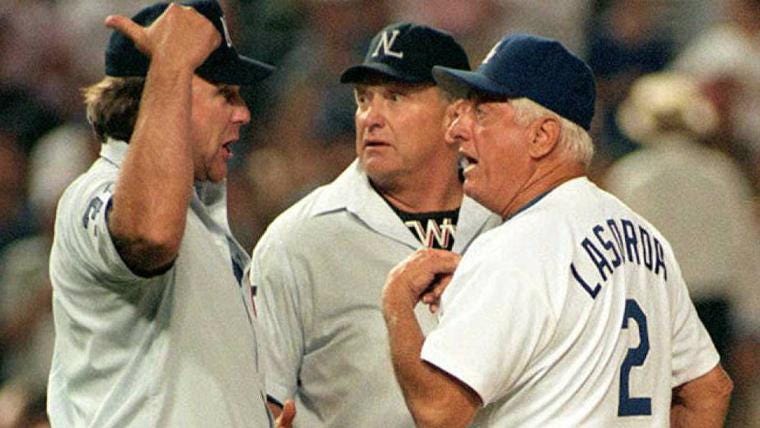

If the fans had missed Karros’ ejection, there was no missing Mondesi’s, and the leather hail began to fall again. Lasorda came out to discuss the situation—and probably Quick’s strike-zone. For a manager with an earned reputation for histrionics, video of the conversation shows Lasorda looking understandably irritated but composed. More baseballs bounced around the conversation. Whatever Lasorda said, Quick didn’t like it, and threw him out, too.

The Dodgers’ vice president and general manager, Fred Claire, felt Quick was set on ejecting the manager:

He didn’t bump [Quick] or anything. He manages with passion. That wasn’t any different than Tommy disputing any other call he didn’t agree with. It’s not as if a very mild manager went crazy—Tommy’s Tommy.

Lasorda raised both hands and waved into the stands behind the Dodger dugout. To our eyes, it was a dismissive, “shooing” gesture, perhaps expressing unhappiness with the people throwing things, but first base umpire Bob Davidson saw it as a “more please” invitation to the crowd.

Balls were landing all over the diamond and in the outfield, and there were folks with decent arms in the upper levels who could reach any uncovered spot. “I asked the batboy if I could trade my hat for his helmet,” Mabry said, “but he said ‘No,’ because he was in danger too.”

The umpires dodged around, looking, according to one reporter, “as if they were tenderfoots in an Old West movie,” dancing as mean-spirited hombres fired bullets into the ground near their feet.

Balls were “raining down from the upper deck,” Mabry said, but, having learned his earlier lesson, he tried to play it cool. “I wasn’t too worried until a bottle of Southern Comfort flew out of the stands and hit me. I got hit by a rum bottle, too.”

The simmering umpires called the players off the field again.

There a five-minute delay as the grounds crew—getting more efficient—filled bucket after bucket with discarded balls. Watching from under cover, Mark Sweeney was impressed. “They must have filled about 15-20 buckets.” Some of the braver batboys chipped in, using their helmets as receptacles. Ushers in old-timey straw hats clambered out onto the dugouts and tried not to flinch.

When the field was reasonably clear, Quick motioned for the teams to resume. “The Cardinals were reluctant to go out onto the field,” Quick said, “but I tried to give [the fans] every opportunity. I thought we’d give it one more try.“

The players had barely returned to their places when a single baseball zipped out of the stands, landing close to Brian Jordan, who picked it up and held it up for the umpires to see.

“You try to be nice,” Jordan said, “have a Ball Night for the fans, it just backfired. I’m not going to stand out there and get busted in the head with a ball. Balls were flying from the upper deck.”

“I saw the ball just miss [Jordan],” Quick said. “It was thrown real hard.” The umpires conferenced for a third time, looking grim.

Waiting on deck, the Dodgers’ Chris Gwynn took an apple to the head. “It was the weirdest thing I’ve ever seen,” Gwynn said. “I’ve been hit by worse things in San Francisco, but these are our own fans.”

The umpires made up their minds. According to Quick, “we were all in complete agreement.”

The crew chief told Bob Davidson to make the announcement. “He told me, ‘Bob, go ahead and whack it, and let’s get out of here.’”

It’s not clear why Jim Quick delegated this historic whack to a member of his crew. “Why Quickie didn’t want to wave it off [himself], I don’t know,” Davidson said. Lasorda contended the forfeit was Davidson’s idea. Either way, the game was prematurely over.

It was the first major league forfeit since July 12, 1979, when the White Sox let a local radio shock-jock dynamite a crate of donated disco records in center field between two games of a doubleheader. One L.A. columnist claimed the Ball Night display was sorrier: “Unlike Disco Demolition, these fans didn’t even have a cause.”

After Mondesi’s strikeout, the Cardinals had roughly a 90% chance to win the game, and they had no objection to wrapping early. “I think most of my players, once they realized what was happening, were relieved,” Mike Jorgensen, the Cardinals’ manager, said.

“As an umpire you hate to do that,” Davidson said. “Games are nine innings, that’s what they’re supposed to be, but this was a dangerous situation.” In the wake of the forfeit, he called attention to Lasorda’s interaction with the unruly crowd:

In my opinion, Lasorda instigated the whole thing, waving his fat little arms out there. I would put the full blame on him, and on management for giving baseballs away before the game. We’ve got to protect ourselves and the visiting ballclub.

“How did I instigate it?” Lasorda shot back. “I was talking to Jim Quick. All I was asking was why he threw my players out. Who made [the fans] throw the balls the first time? What did I do? If I don’t come out and ask why my players are being thrown out, what kind of a manager am I? That’s all I did. I tell you, that is a real crime, for those guys to try to put that blame on me.”

“Lasorda provoked the whole thing,” Cardinals catcher Tom Pagnozzi said. “I hope they lose the division by one game.”

The umpires drove back to their hotel in Pasadena. A look at the rulebook revealed that, having called a forfeit, they were required to immediately notify the League President, Len Coleman, who was fast asleep at home in New Jersey. But rules were rules. After some foggy introductions, Quick cut to the chase.

“We had to forfeit the game here at Dodger Stadium.”

Now Coleman was awake. “What? You guys did what?”

“Yeah, we had a forfeit,” Quick repeated. “We gave them three chances; they gave away 45,000 baseballs before the game, and not one fan has a ball now; they’re all on the field.”

The next day the umpires traveled to their next assignment at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, home to the Dodgers’ ancestral enemies, the Giants. Word of the their decision in Los Angeles had preceded them, Davidson remembered.

As the they walked onto the field, “the Giants’ players gave us a standing ovation.”

The loss put the Dodgers one game back of the first-place Colorado Rockies. “I just hope and pray that forfeit doesn’t cost us,” Mike Piazza said. “If we lose the division by a game, man, you’re going to have some upset people around here. That’s why we have to get a comfortable lead so we don’t have to think about that game anymore.” The Dodgers won the NL West by a single game and never led by more than two games.

The forfeit was the only Cardinals victory in a 10-game span. Closer Tom Henke asked whether he’d get a save for making one of three needed outs. This was confirmed2; it was Henke’s 299th save. “I’m glad that wasn’t my 300th. Can I call up and request two strikeouts for those last two outs? You know I was going to get them.”

Fred Claire said the Dodgers would appeal the forfeit:

It’s very unusual for something like that to take place here. We have asked the league president to review the circumstances leading up to the umpires’ decision to forfeit the game and to determine that all the rules were followed.

Davidson was adamant that the umpires had followed the most fundamental rule of them all: “We gave them three chances,” he said. “Three strikes and you’re out.”

The Dodgers’ appeal focused on a lack of warning from the umpires to the fans that their actions were risking a forfeit, but this was a rather fine splitting of hairs. Day-after reports agree that the fans were warned twice—over the public address system and via the electronic message board—after the seventh inning and ninth inning salvos. Jorgensen, the Cardinals’ manager, said the announcements stated that throwing things could affect the outcome—“and it did.”

On August 24, Coleman did his presidential duty. After pretending to think hard for several weeks, he denied the Dodgers’ appeal:

The safety of players, umpires, and, of course, the fans themselves must be paramount. In a real sense it was fortuitous that no one was hurt; baseballs were thrown randomly onto the field, some from the upper deck…I believe the conduct of several hundred fans on August 10 created sufficient danger that the umpire’s decision to forfeit the game was justifiable and correct.

“I disagree [with the ruling] and am disappointed in it,” Claire said. “My hope now is that this will lead to much clearer, precise guidelines3 on the forfeit rules. I hope something constructive comes out of it for the good of the game.”

Mike Piazza observed that the forfeit created at least one opportunity for the Dodgers organization: “They could do the promotion again,” the catcher said. “They got all the balls back.”

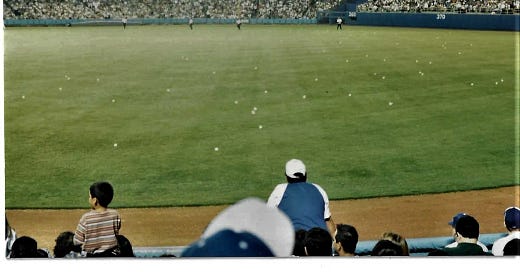

But did they, really? How many balls were actually returned?

On the one hand, umpire Bob Davidson later recalled that “15,000 balls” were thrown in the seventh inning alone—a preposterous claim, as only that many balls were even distributed.

On the other, a member of the Dodgers marketing department tried insisting “about 20” baseballs were tossed—but there are three times as many in just this one picture:

The Dodgers eventually admitted they retrieved about 200 balls. If you assume the Dodgers were still fudging downward, there’s Sweeney’s report that the ninth inning volley filled “15-20 buckets.” If we take the low end there and assume 12 balls per bucket, that’s 180 balls, and the first and second volleys were generally judged to be similar. Let’s call it 361 balls, accounting for that final missile thrown too close to Brian Jordan, the night’s symbolic “strike three.”

And while there may not have been thousands of missiles flying on Ball Night, let’s not forget that each ball was initially placed in the hands of a child aged 14 and younger. Can you think of a demographic less likely to toss away a gift baseball? We can’t. The truly remarkable Ball Night stat is that hundreds of adults seem to have taken their child’s souvenir and sacrificed it to protest Jim Quick’s raggedy strike zone. “You’ll understand when you’re older, Timmy.”

After the forfeit, everyone assumed a beloved Dodger tradition had ended, but the team promised to find a way forward.

“We’ve had Ball Night for 20, 25 years,” the team’s VP of Marketing said. “We will continue to have Ball Night. But we will look for other ways to distribute the baseballs.”

In the league office, a spokesperson said they might make that suggestion to all teams, and there was good precedent for this:

Years ago we suggested bats not be given out, at least pre-game. If you give them to someone, give them to them as they leave the park.

By 1998, Ball Night had become Ball and Glove Night. The gloves were handed out on entry, but a coupon system was used for the balls. Rather than send kids to Target or wherever to collect their prize, the PR-genius Dodgers left the giveaway balls in the city’s fine public libraries.

This combined/hybrid approach also had a substantial cost-savings for the Dodgers, as one father pointed out:

As I looked around the stadium, I saw a ton of kids trying out their new mitts, all crumpling their library coupons into makeshift balls and eventually throwing them away.

Every discarded coupon was another ball the Dodgers could save for next year’s giveaway.

And that is how you do a promotion twice.

Share your own memories from Ball Night(s)!

O’Malley permitted one extravagance. The Dodgers’ fourth pillar of promotion was a “Hollywood Stars” game, in which the team took advantage of California’s chief natural resource, staging an exhibition contest featuring teams of actors.

As far as we can tell, this is the only time since World War II (and perhaps longer) where pitcher won/lost records from a forfeited game were kept. We can find no reason for the change, or even any indication that people at the time were aware that this was a deviation from past practices. A good reminder that what we today call history was once just people making stuff up.

No new forfeit guidelines ever came. Perhaps it was easier to tell the umpires they shouldn’t call any more forfeits.

I found the guy with the batting helmet, and, curiously, it looks like an Expos helmet. That tracks, because me and my brothers always chose more interesting batting helmets as souvenirs than our hometown Cubs.

Oh Paul, I guess I’m the only nitwit who looked for the guy with the helmet! And found him! (The very left of the right hand third of the picture.) This post was so entertaining. Apparently nuns and boy scouts are drawn more to day games, and dairy farmers/workers and letter carriers love the nightlife! Thanks. Meg