(After) The Battle of Atlanta

Near the end of a landmark season for brushback brawls, the Braves and Padres renewed their rivalry in San Diego.

This is the conclusion of a three-part baseball saga of implied orders, unwritten rules, and ridiculous machismo. For those just joining us:

At the end of their August 12, 1984 battle, the Braves and the Padres left Atlanta (hopefully via separate terminals at Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport).

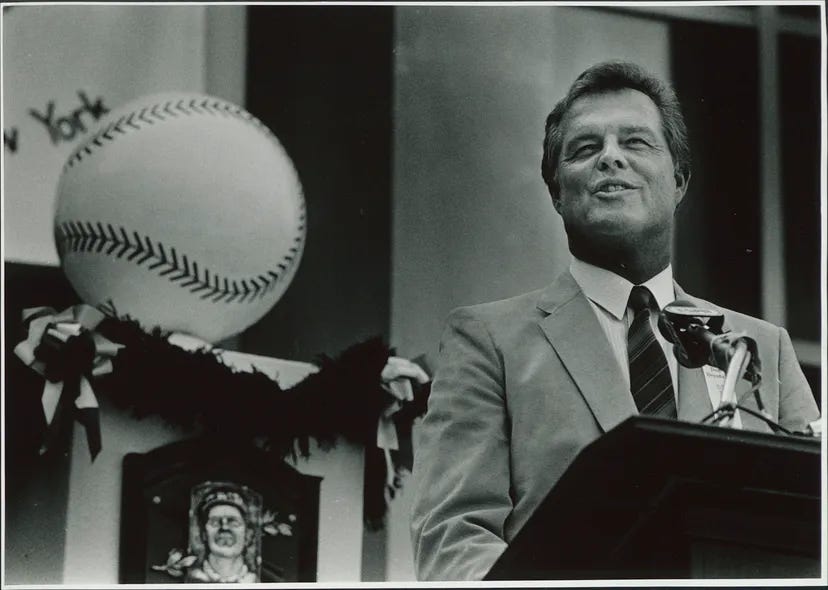

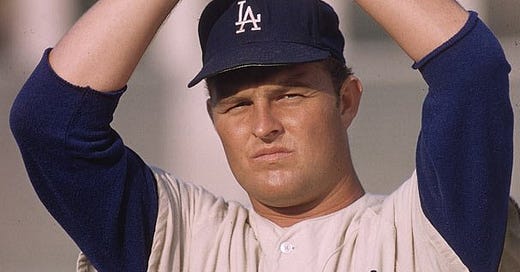

The Braves were off to Cooperstown, New York, to play in the annual game accompanying the Baseball Hall of Fame induction ceremonies. That year, the Hall welcomed Rick Ferrell, Harmon Killebrew, Luis Aparicio, Pee Wee Reese, and Don Drysdale.

Drysdale, then a commentator for the White Sox and ABC Sports, was frequently invoked as one of the founding fathers of modern inside-pitching, and as such was an ideal pundit for the moment. That October, he was prominently featured1 in an extended segment on ABC’s Nightline program discussing baseball’s beanings and brawling.

The segment began with a five-minute montage of the season’s various gladiatorial bouts, set to Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger.” The Braves/Padres altercation was prominently featured. In a subsequent panel discussion, Drysdale was asked if anyone had gone too far that day in Atlanta.

“What happened over there was that San Diego’s pitchers had bad aim,” Drysdale said. “It took them too long to get [Pérez].”

“The pitcher has to have a certain part of the plate which is going to be his,” Drysdale explained, “and the hitter can have a certain part of the plate that is going to be his. I always maintained that. I just don’t want to have to tell you which part of the plate is going to be yours on this particular pitch, that’s all.”

The host, Charles Gibson, asked what message brushbacks and fighting sent America’s kids. Drysdale disavowed headhunting, saying “I’ve never thrown at a man’s head in my life,” before echoing a common refrain from baseball insiders asked about violence within the game.

“Look, this is a job. This isn’t a Sunday pick-up game for a keg of beer. This is a man's livelihood, a family’s livelihood.” It was baseball-as-nature-documentary: brightly-colored males battling over disputed territory.

Drysdale’s Hall of Fame induction took place the same day as the brawl in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, and it remained the talk of Cooperstown when Joe Torre and the Braves arrived there 24 hours later. Atlanta played an exhibition game against the Detroit Tigers in front of 10,000 happy fans. Even in his free time, Torre found the brawl hard to escape.

“Everywhere I go, that’s all people want to talk about,” he said. “I went out to dinner last night and at the end of the meal, the waiter said, ‘I like the way you stuck it to that guy.’ I said, ‘What guy?’ And he said, ‘You know, Dick Williams.’”

The Padres, meanwhile, were in Philadelphia, taking 2 of 3 from the Phillies and trying to lay low—NL president Chub Feeney and the league owners were just a few streets over, holding the annual summer meetings.

At Veterans Stadium, Dick Williams ran into an old acquaintance—Richie Ashburn. The two men had reached the majors at about the same time and played against each other for several years in the 1950s. Ashburn was now an announcer for the Phillies, but he also moonlighted as a columnist for the Philadelphia Daily News.

In this latter capacity, Ashburn asked Williams about the fight. The manager briefly feigned reluctance (“I really shouldn’t say anything…”) before diving in head-first—Ashburn got just a single question into what was otherwise a monologue.

Without providing any evidence, Williams again claimed the Braves “had a meeting before the game,” apparently to discuss how to “stir things up” after his team beat them twice in a row and buried them in the standings. “Maybe Joe’s fighting to maintain his job. I don’t know.”

“I think it was definitely deliberate and so do 99 percent of the people who were in the press box. [Pérez] hit two men in 135 innings and he even said on tape he has flawless control.”

Ashburn’s one question asked the manager why it took the Padres so long to collect their bounty.

“I’m not sure what all happened out there later in the game,” Williams said. “I wasn’t there. I was thrown out of the game and was in the clubhouse. Joe called me gutless for not getting involved in the fights. I couldn’t go on the field. If he wants a fight, I’ll go anywhere he wants. I’ll go on the street corner. He accused me of using “Hitler-like” tactics. Well, you can tell Benito (Mussolini, presumably) that I don’t give a damn what he thinks of my tactics.”

The Padres’ manager said he would “go to his grave” believing the hit on Wiggins was intentional. “So, one thing led to another. We went after one man. That was Pérez. That’s been done before.”

On August 16, Chub Feeney doled out National League justice.

For returning to the field after being ejected, three Braves—Steve Bedrosian, Rick Mahler, and Gerald Perry—received three-day suspensions. Joe Torre received the same penalty, plus a $1,000 fine, largely for failing to control Donnie Moore.

Most of the 16 fines ranged between $300 and $750. All the ejected pitchers were fined, as was Pascual Pérez. Pérez—who was never ejected—received the smallest punishment given to anyone: a $300 fine.

That left Dick Williams. The Padres’ manager received a ten-day suspension and a $10,000 fine. Of Williams, Feeney said, “the field manager is held responsible for the continuing incidents involving his players that led to serious altercations on the field.”

Dick Williams was shocked. Shocked. “This is three times longer than I expected to get,” he told a reporter. “I thought [Padres general manager] Jack McKeon was kidding when he read [the sentence] to me.”

“The warning rule allows for no retaliation,” McKeon complained. “It’s OK to be the first team to hit somebody, but not the second.”

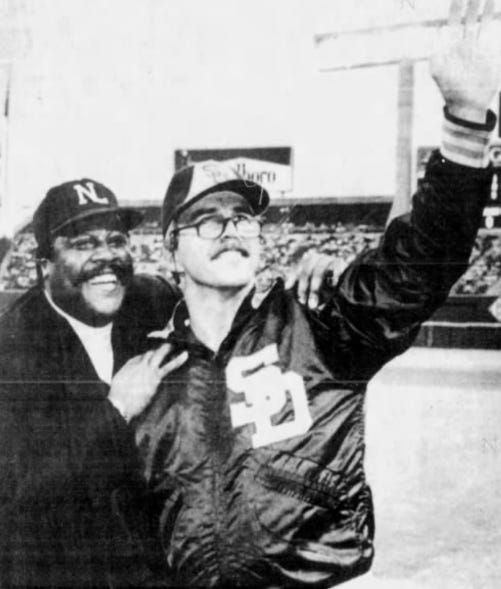

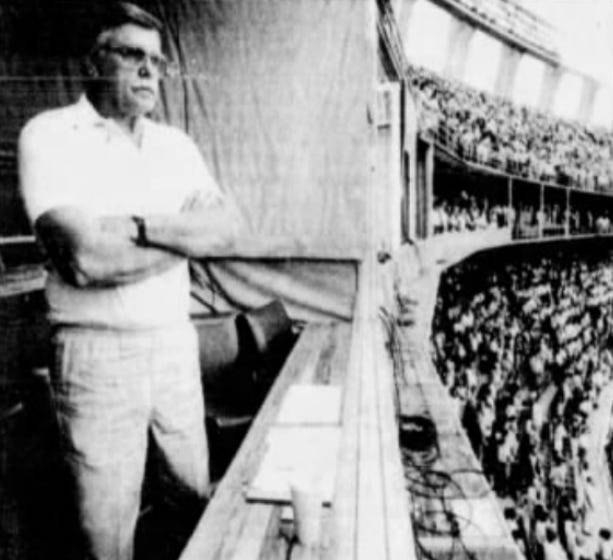

Having lost their manager, the Padres responded by losing their first three games under interim manager Ozzie Virgil. During an August 20 game against the Mets, reserve infielder Kurt Bevacqua decided to inspire the team by taking Williams’ place, frosting his hair and his comparable mustache, donning thick glasses, and delivering the lineup card as the manager typically would. Everyone enjoyed it, except perhaps for Williams, stuck up in the team skybox like the Grinch atop Mt. Crumpit.

Summer turned to autumn and the Padres continued to roll, never relinquishing the sizeable lead they’d built over the rest of their division. The Braves’ elimination number drew closer, as did their visit to Jack Murphy Stadium, where 120,000 people were expected to attend the rematch. An NL official promised that any follow-up antics “would be dealt with in the most severe way possible.” The Padres were boosting security. “We’ll present a solid and firm front and hope that curtails anything that might otherwise happen,” a security official said, adding “I don’t think the Southern California fan is as volatile as the fans back east.”

The Padres’ prefatory comments suggested they had seen the error of their ways.

Bobby Brown, who had once promised a sequel, said, “I was just mad, you know how it is.”

“It was the heat of the moment,” Champ Summers said. “Both teams have too much class to let it get out of hand again. If I was a betting man, I’d bet that nothing would happen here.”

Ed Whitson said he hoped that the players would “behave like gentlemen,” signaling that he would at least wear a shirt and shoes this time around.

Even Dick Williams was diplomatic. “When I take the lineup card to home plate, I’m going to extend my hand to Joe Torre. Hopefully he’ll accept it. We’ve dropped it. Hopefully they have, too.”

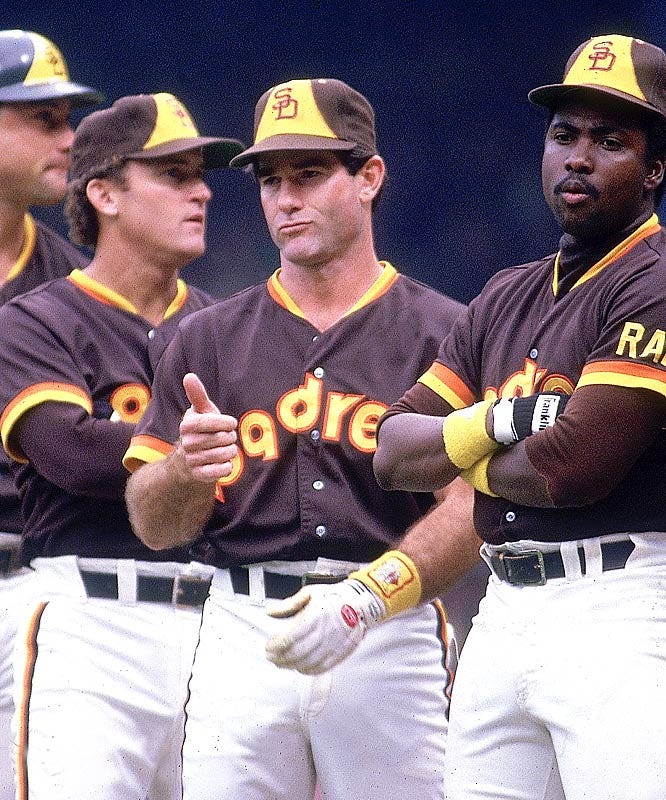

But the single biggest factor keeping the peace may have been the fact that on the day the series opened, the Padres were playing hung-over.

The previous day—September 20—their win over the Giants and an Astros’ loss elsewhere delivered San Diego its first-ever postseason berth. That night, Rich Gossage threw a party for the team at his home in the Tierrasanta community. The players and select members of the front office toasted their victory and reportedly took turns throwing one another in Gossage’s pool. Ever the instigator, Kurt Bevacqua said he’d dumped spit-and-polish Steve Garvey in to get things going—Garvey called the claim “Napoleonic.”

“Garv went in with a shirt and tie on,” McKeon, the general manager, said, “and came up without a hair out of place.” Next in was Joan Kroc, the widow of team owner and McDonald’s magnate Ray Kroc, who had died early in the year. In and out of the water, libations flowed.

The team was understandably subdued the next day. “I just wanted to get through this game without throwing up,” Tim Flannery said afterward, “and I did.”

The Padres shot off celebratory fireworks before the game and received a three-minute standing ovation from the fans. The Braves were duly booed, even during their batting practice, but there was applause when Joe Torre and Dick Williams met at home plate and exchanged a firm handshake.

“Things happen and everybody gets mad,” Torre said. “When things are over, it’s just like yelling at an umpire. Unless you let things like that pass, you’re going to run out of people to talk to.”

The wobbly Padres lost the uneventful game, 3-1. But the second game was the marquee match-up, featuring Ed Whitson and Pascual Pérez.

Since the brawl, Pérez had a 1-3 record with a 3.35 ERA. Scouts watching him said he had changed his style, and seemed less willing to throw inside. Without that part of the plate to work with, he’d allowed seven home runs in the past 39 innings, a notable spike.

The pitcher had spent the previous night walking around with his cap pulled low over his eyes, muttering “I’m scared,” in Spanish, half-joking, half-serious, but Torre hadn’t pulled him in Atlanta and wasn’t going to do it in San Diego, either. “It’s his turn,” Torre said, “and I asked him about it. Pascual said he didn’t want to back off.” Pérez likely didn’t want to back off the incentive clause in his contract, which would pay him an additional $25,000 for throwing a number of innings he had yet to reach.

The pitcher showed what might have been nerves when he opened the game with four straight pitches that missed outside, but this may have been merely gesture of rapprochement, as he went on to pitch eight innings and give up only two runs.

The Padres helped his cause by fielding an all-reserve lineup, hoping there would be less animosity in a stars-versus-scrubs affair. The only regular was Whitson, and he was indeed a perfect gentleman.

The Southern California fans were as advertised, quickly giving up on revenge in favor of flying paper airplanes in the stadium and doing the “Wave.” They got it around the stadium a full eight times, and even some of the San Diego bench joined in. The Braves won again, 5-2.

“I was pleased with our fans,” Dick Williams said, “for just booing and not throwing anything. [Pérez] was in open spaces a few times. You just have to hope that nobody takes a BB gun or something stronger.” Yep, real quote.

Afterward, Pérez declined to speak to the press. “He has nothing to say,” teammate Steve Bedrosian said. “He just doesn’t want to talk about anything.”

The two teams had one more series together, finishing the season in Atlanta. But the Padres were clearly looking forward to the playoffs and Pérez and the Braves were eager to put it all behind them.

“I don’t think there’s any animosity left,” Williams said. “There shouldn’t be. It’s all in the past. It should be nice and peaceful now. But we did what we had to do. If the same thing ever arises again, we’d do the same thing.” Perhaps, but the manager also announced he would be skipping the final series in Atlanta in favor of a scouting trip to Chicago, to get a good look at the team’s playoff opponent, the Cubs.

The Padres won the first two games in Atlanta, playing in front of small, diffident crowds at the end of a sub-.500 season. “I thought they’d have a 12-gauge shotgun night at the stadium when we returned to Atlanta, but that never happened,” catcher Terry Kennedy said.

The Braves needed a win in the final game of the season to tie for second place in the division. The game lasted a perfunctory hour and 39 minutes, the shortest duration of any contest that season. Pascual Pérez pitched another strong eight innings and recorded his 14th win in a season he hadn’t started until mid-May. The victory earned each of his teammates an extra $3,000, and perhaps $28,000 for Pérez himself.

Then and later, some of the Padres said the fight in Atlanta had forged tighter bonds among the team. They even admired the unorthodox lengths their manager had gone to in order to when he felt they were being disrespected. Williams, a manager famously known for treating his players “like s***,” had shown he wouldn’t tolerate others doing the same, and that was something. More importantly, the players saw how far they would go for each other.

“It brought us closer together,” Kurt Bevacqua said in 1994. ”It was something unsaid. We didn’t sit around and say, ‘This showed how unified we are,’ it was just a sense that we were in this thing together.”

“We found out that we’d protect each other,” Bruce Bochy said.

Baseball is a team sport built out of long chains of individual actions and responsibilities. The pitcher throws, the batter swings, the outfielder catches, the runner tags, building the game link by link. Baseball fights, on the other hand, are swirling, simultaneous, all-hands-on-deck chaos, in which even bullpen guys like Bruce Bochy have to run out and find ways to make themselves useful. Beneath all the performative machismo, these team-building exercises give players a chance to take stock of each other in the moment, in the video room afterward, and in stories retold for years to come.

A good fight has its place in the game, but 1984 was a year of splashy violence and mean edges in baseball—full of entitlement and anger as the cold war for the airspace above home plate often turned hot. The sport ended up on Nightline, after all, and not for majestic home runs, slick plays, or records broken. Instead, the story of the season was told with a montage of brushbacks, drillings, and coast-to-coast bedlam.

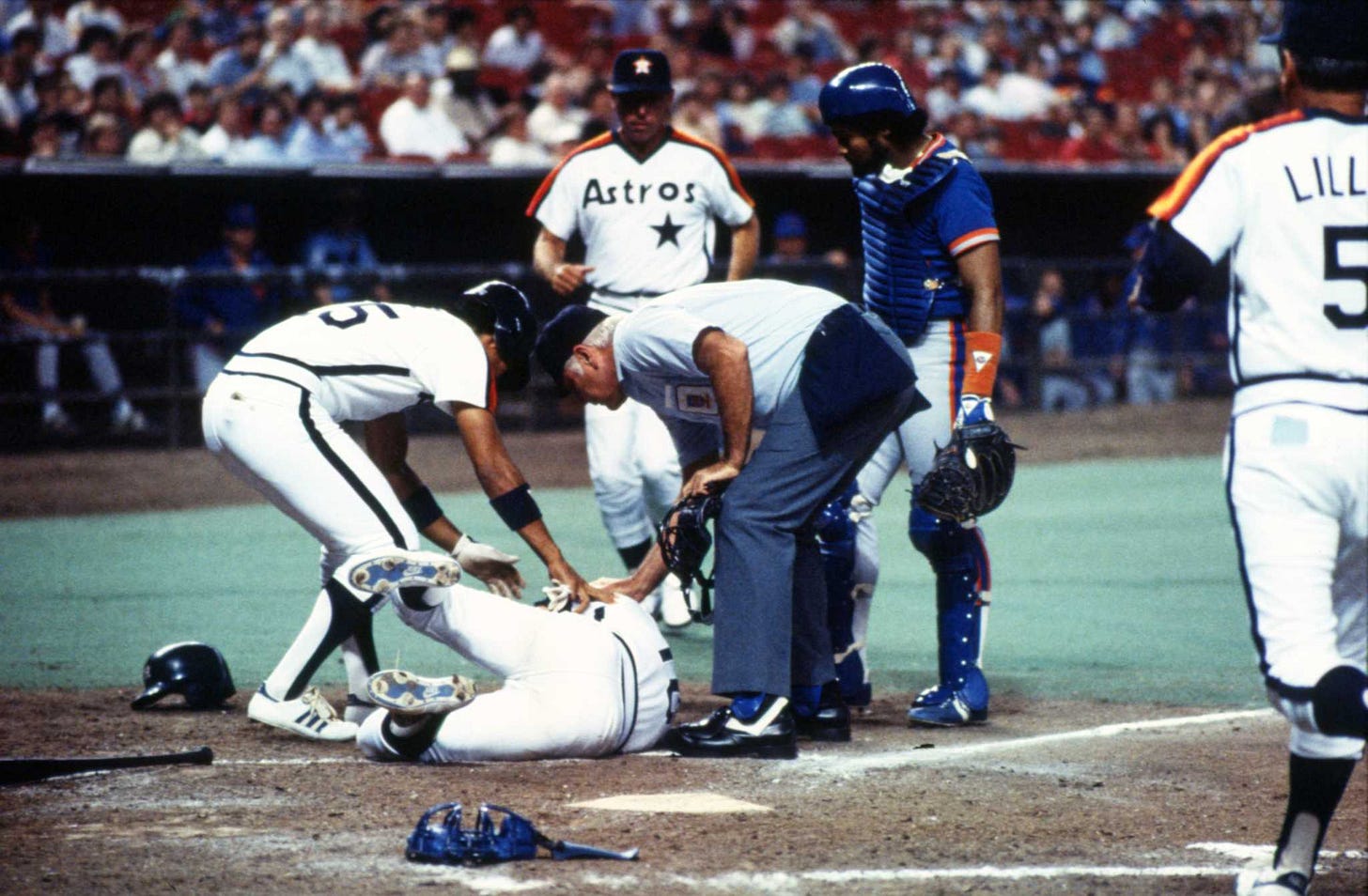

The Nightline montage ended with an extended clip of Houston’s Dickie Thon being struck by a “sailing” fastball, and crumpling to the ground. Not even that lingering image persuaded Don Drysdale that the game had a problem. And even if there was something going on, Drysdale said more rules made by suit-and-tie guys would do more harm than good.

“Baseball has been here for well over a hundred years,” he said. “Let the players play. They’ll take care of it.”

By September 1984, Dickie Thon could correctly call out a few letters on the 20/40 level of the eye chart, but he would later admit he got so familiar with the tests that he made some educated guesses as he tried to get cleared to return to the field.

In December, he’d made enough progress to try playing winter ball in his native Puerto Rico. In his first game, Thon hit a home run. After that, however, he went 0 for his next 8 at-bats, mishandled a double-play ball, and threw off-target to first base. He said balls looked like cotton wads coming off the bat and his depth perception was off. Thon benched himself. “I have to be honest. I can’t say I am going to play if I can’t play.” He’d try again during spring training.

Mike Torrez had been released by the Mets in June. The errant fastball he’d thrown on April 8 might have had been his most consequential pitch that year, but no one blamed him, including Dickie Thon.

“I blame myself,” Thon said. “I think, ‘Why did I let this happen?’ I just stood there.”

He dreamed about the pitch, sometimes. In the dreams, he saw it coming, saw it clearly, but he could never get out of the way.

Next week, let’s change things up, with a story from 1987, and the tangled webs between baseball and pop culture.

On February 3: “A New York Wedding”

The Nightline anchor, Charles Gibson, didn’t come across as much of a baseball fan. His arch and minimalist introduction of Drysdale, one of the most accomplished pitchers of his generation: “Don was known for a high inside pitch that many batters found menacing.”

A quiet end to a fiery event. Drysdale retired just before I began watching a lot of baseball. My introduction to him was in cameo appearances in shows like The Brady Bunch.