A Spring Training Story: The Three-Ball Walk

In 1971, Charles O. Finley, baseball’s master disrupter, changed the rules and clogged the bases.

This spring, after careful testing in the minor leagues, major league baseball brought technology to the strike zone, piloting a challenge system that gives teams a limited number of chances to question whether the home plate umpire got it right. The system is quick, painless, and—by all evidence—a great success. Baseball may implement it for the regular season in 2026. Can’t be too hasty.

Spring training has long been a testing ground for new ideas. Some, like the Automated Ball-Strike system, are establishment plays. But the game’s rebels have also used exhibition season to wage their own pet insurgencies, with varying results.

The idea wasn’t new. Frank Lane, the 72-year-old general manager of the Milwaukee Brewers, said he’d been talking about it on and off for 20 years. But in the winter of 1971, a new champion emerged, and he was always on.

“Make a walk three balls instead of four,” Charlie O. Finley declared. “The excitement in baseball comes when men are on base, so let’s get more men on base.” It was a sound byte and a cause.

In 1971, Finley, the owner of the Oakland Athletics was regarded as an excellent judge of baseball talent. His Swingin’ A’s were on the cusp of relevancy, soon to embark on a historic back-to-back-to-back championship run. But as one of the sport’s chief iconoclasts, he was disliked by nearly everyone.

“There is absolutely nothing so sacred that Charlie Finley, the noted revisionist, cannot assault it with both hands,” a skeptical columnist wrote that March. “There is an eagle on the flagpole at the Oakland Coliseum only because Charlie can’t figure out a way to get a mule up there.”

In a February interview with the Los Angeles Times’ Charles Maher, Finley said he’d began noodling with the idea of a three-ball walk in the mid-1960s, but a recent visit to the sports research library at San Jose State College—one of the nation’s largest—had converted him.

“I asked them to dig something up on balls and strikes,” Finley said. “I wanted to find out how aggressive baseball has been in its thinking over the years.” The answer was: “not very.”

Finley gave Maher a quick history lesson1:

Prior to 1879, baseball only had strikes, and you got four of them. They didn’t count balls. A player could come up and stand there for 10 minutes, waiting for the pitcher to throw his particular pitch. They were not getting much attendance then. People were literally bored with this guy standing up there waiting for his pitch. As a result, the owners decided to do something. So the ball and strike count was introduced in 1879. Four strikes and nine balls. The fans showed some acceptance and enthusiasm. The following year, they reduced it to eight balls and four strikes. In 1881, they made it seven balls and four strikes. Finally, in 1889, the four-and-three count was instituted.

Finley’s underlying point was that neither Abner Doubleday nor Henry Chadwick ever handed down a tablet engraved with four balls and three strikes. So why did modern baseball treat those numbers like commandments?

“Baseball has got to be more aggressive in its thinking,” Finley said. “Children—and I have seven of them—are looking for things that have action, action, action! But unfortunately there are other sports that have come along and made their games more interesting. And we in baseball sit around like a bunch of stupid, fat slobs and do nothing about it.”

He believed that the increasing sophistication of modern pitching had rendered four balls unnecessary. “Today [pitchers] can hit a batter on the left ear or his belly button, they are so accurate.” Finley thought modern pitchers could get by with three balls, and the lower number would force them to throw more pitches in the strike zone where batters could turn them into “action.”

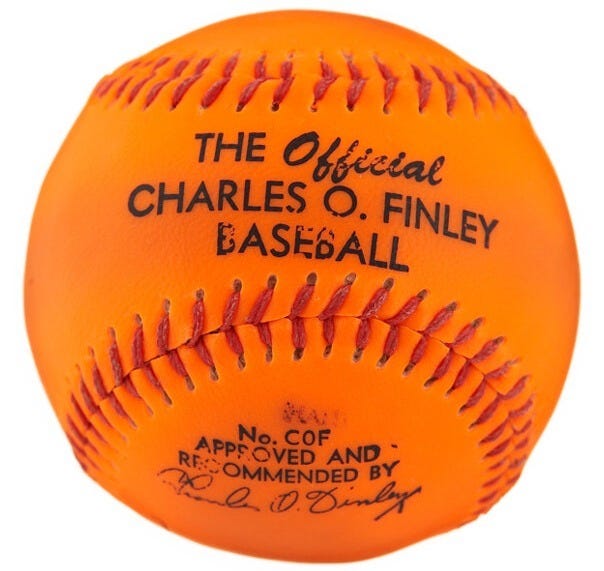

In 1971, Finley’s record as an innovator was mixed. Despite his best efforts, neither mules nor Day-Glo orange baseballs caught on. On the other hand, baseball quickly embraced Finley’s idea to start the World Series on weekends, ensuring that a long series would end on a weekend, too. More recently, he’d led the charge for nighttime World Series games. The owner excoriated baseball for scheduling its most important contests when most working people couldn’t watch. In October 1971, the World Series took place partly under the lights, and that seems to have worked out okay.

Whatever the initiative, Finley’s involvement guaranteed plenty of friction. “Some people in the game regard Charlie as a whacko,” Maher explained, “while his best friends merely consider him wildly eccentric.”

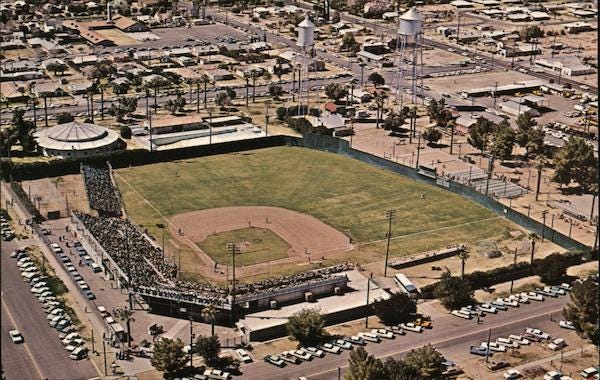

The three-ball walk experiment began with an intrasquad game on March 2, 1971. Two groups of A’s faced off at Rendezvous Park in Mesa, Arizona, the team’s spring training home. Finley was not there to see it—he operated almost exclusively by phone, holed up in the Chicago headquarters of his insurance company.

As always, the owner was wearing out his long-distance phone service, leaning on the American League president, Joe Cronin, and the commissioner, Bowie Kuhn. Finley assured reporters that Cronin said the three-ball walk was “a tremendous idea,” and gave him permission to test it over the course of the spring. To hear Finley tell it, the change was already becoming a fait accompli: “I asked [Cronin] to get rolling on it immediately because it would take baseball 25 years to adopt it, and I would like to see it adopted before I pass on.”

In the battle of the A’s versus the B’s, both sides combined to issue 20 three-ball walks, an eye-popping number. This wasn’t action, but it was early.

The first real test came on March 6, when Frank Lane’s Brewers came to Mesa to face the A’s. Lane and Finley appeared to be deep in cahoots, reading from the same declarative talking points (“Make a walk three pitches instead of four!” and so on). The Brewers’ general manager acknowledged how strange it was to find himself in agreement with Charlie Finley. Lane had (briefly) worked for Finley in 1961, during the Kansas City A’s era—that collaboration ended in a lawsuit.

While Finley sought more action, Lane was trying to cut time. Baseball games were too long, and modern pitchers a big part of the problem:

What made me think about this was a pitcher we used to have with the White Sox in the 1950s by the name of Saul Rogovin. He’d always start by getting two strikes on the batter and then I could close my eyes and say, ‘hurry up and throw the next three pitches and get the count to 3-2,’ and that’s invariably what would happen.

With two strikes, pitchers inevitably began nibbling, trying to get the batter to strike out on a pitch on the edge of the zone or outside it altogether. More and more, pitchers were using all three of their nibbles instead of challenging hitters. Lane felt “waste” pitches were also wasting everyone’s time before the inevitable full-count showdown began.

“There haven’t been any significant rule changes in 80 years,” Lane said. “Maybe we ought to consider some.”

After a month on the stump, Finley had successfully planted his idea into the zeitgeist of the baseball-going public. Over the public address system at Rendezvous Park, an announcer told the small crowd, “Today’s game is being played under the three-ball rule,” assuming people would know what that meant.

Judging by the groans and a smattering of boos, many people did. One fan shouted, “Bring back baseball rules!”

26 hits and 20 free passes later, the game ended in a 13-9 A’s victory. Dick Williams, the A’s newest manager, put on a brave face.

“I’m all for it,” Williams said. “The idea is to get more baserunners and score more runs for the fans’ entertainment—and they saw 22 runs out there today.”

Finley and Lane had earlier agreed to also use the rule at Diablos Stadium in Tempe, where the Brewers played, but after the first attempt the Brewers’ pitching coach, Wes Stock, put his foot down. “I told my players to forget about it.” The Brewers won a traditional contest, 3-2. “Today was much more fun,” Stock said.

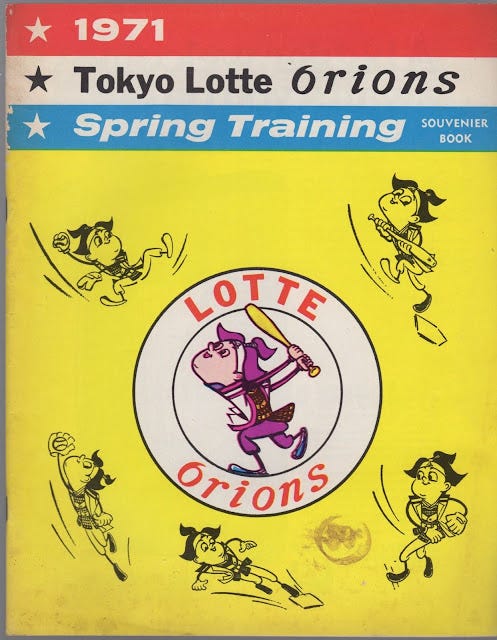

Finley improvised. The Tokyo Lotte Orions of Nippon Professional Baseball were holding their spring training in Arizona, guests of the San Francisco Giants. The Orions joined the Cactus League circuit, and on March 10, Finley took advantage of his Japanese visitors, announcing that the game would be played under the three-ball rule. Despite having virtually no notice of this change, the Orions responded brilliantly. Their six pitchers issued only three walks between them. Meanwhile, five A’s pitchers walked 16 Tokyo batters. The Orions had opened their tour with five straight losses, but Finley’s new rule played right into the strengths of Japanese pitching, and the Japanese club won their first game, 11-6.

Earlier that winter, several weeks before camps opened, Finley had called Dick Walsh, the general manager of the California Angels. With typical braggadocio, Finley told Walsh that the American League had given him carte blanche to test the three-ball walk during the A’s home games that spring.

Walsh was cautious. He told Finley he’d need to see that in writing. Three weeks went by with no word, and Walsh forgot about the whole thing. On March 10, the Angels arrived in Mesa.

In the absence of the owner, who also acted as his own general manager, the A’s were run by Phil Seghi, officially the “minor league coordinator.” Seghi reminded the Angels that, as per the League Office, the game would utilize the experimental walk rule.

In turn, Walsh reminded Seghi that he’d expected to receive notice of this formally and in writing. No problem, Seghi said. He disappeared for a few minutes and then returned with a press release, written by Finley:

Kuhn and Cronin have authorized the A’s to play all their games in Mesa against American League clubs with the three-ball, three strike experimental rule. It is with this authority that we are playing with the three-ball rule today.

Well, it was in writing.

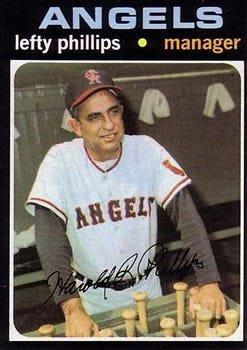

The Angels’ manager, Lefty Phillips, was unimpressed. “That release means [blank].”

“No insurance agent is going to dictate to me,” Phillips said. “He may be used to telling his people what to do but he is not going to tell us what to do. He didn’t even have the courtesy of asking me. He went right over my head to Walsh.”

Walsh, for his part, tried to reach Cronin in Boston or Kuhn in New York, but no one could come to the phone. Someone in the commissioner’s office reportedly told Walsh that, yes, Finley had gotten permission to run his experiment, however, “agreement from both messengers might be necessary.” Might be?

With no leadership coming from baseball’s leaders, Walsh tried to work it out with Finley directly.

In a short conversation, Walsh told Finley the Angels would not play under the rule, having received no notification from the League. Finley called Walsh “a [bleeping] idiot.” Walsh hung up.

Now Finley called Rendezvous Park and had someone put him on with Jerry Neudecker, head of the three-man umpiring crew working the game. Neudecker then tried to call Cronin and Kuhn, with similar results. First-pitch was approaching, and in a world without cell phones, the umpire had to make the call on his own.

“I have just talked to Mr. Finley,” Neudecker announced, “and he assured me the A’s have permission, so we are proceeding with the three-ball rule.” Asked if he’d talked to anyone else, the umpire said, “No, I have talked to no one except Mr. Finley. If he wasn’t being honest with me, that’s something else again.”

Phillips considered leaving, telling his players, “I may take you guys home.” He ultimately decided to play Finley’s game out of respect for the (small) crowd who’d come out to see the game. “I would not be so petty as the man who introduced the rule.”

Some fans probably wished the Angels had left. As the long-distance phone deliberations played out, a man leaned over the railing and asked a reporter if the teams were using “that confounded three-ball stuff.” Told that was the plan, he got up and walked out, saying he would “rather pay to see frogs fight.”

The Angels gave up 11 walks to Oakland’s six—the A’s pitchers seemed to be getting the hang of things—and Oakland won, 6-1.

“They forced us into playing their game and I don’t like it,” Phillips said. “Maybe next year we’ll experiment with four outfielders.”

Dick Williams started to buckle.

“The main purpose was to have more hitting in the games,” the manager said. “We knew there would be more walks, but didn’t think there would be as many in our first two games.”

Dick Walsh of the Angels lodged a complaint with the commissioner. The Angels refused to play the A’s again. Kuhn, making his rounds through the camps, promised to sort things out when he visited Arizona in the coming days.

Finley complained to the press: “Most people in Southern California seem to be against any kind of change at all.”

Finley’s list of co-conspirators was shrinking. Bud Selig, the Brewers’ owner (and Frank Lane’s boss) was heard “knocking” the three-ball walk. With Lane neutralized, only one supporter remained—yet another former employee Finley had previously terminated—Alvin Dark, now the manager of the Cleveland Indians. Dark was so interested he agreed to use the three-ball rule in his home park in Tucson.

“I like to see pitchers work on hitters,” Dark said, “but I don’t like ball one, ball two, strike one, ball three, strike two.”

The March 16 game between Oakland and Cleveland featured 23 walks. Some fans began booing every base-on-balls. The Indians’ farm director buried his head in his hands. “I thought we talked Alvin out of this. It’s terrible.”

The Indians issued 15 walks overall, while the A’s Vida Blue gave up all 8 for his side, over six innings of work.

Even after setting a new record for free passes, Dark was undeterred. “The next time we’ll know that we have to throw strikes,” he said. “It’s good to try. The time to experiment with rules changes is in the spring. I wasn’t disappointed at all.”

The teams played again the next day, this time in Mesa. Bowie Kuhn was in the house, on hand to personally deliver a set of patronizing and boilerplate warnings to the players, the same ones that were already plastered in every clubhouse: “Don’t do drugs, and, whatever you do, don’t gamble.”

The shirtsleeves commissioner watched as the teams walked 18 batters (12 for the Indians, six for the A’s). His team won the game, but Finley was about to lose the war.

“We have been keeping tabs on the number of walks given up during these early spring games,” Kuhn told a local writer. “From what I have seen thus far, the number of bases on balls is excessive.”

The lawyerly Kuhn did his best to avoid antagonizing Charlie Finley in his own park:

I believe there should be a little more testing done before we make a final judgement on the suggestion by Finley. Let’s continue the schedule as set up this spring and then survey it during the meetings of the American League clubs.

That sounded almost supportive, or at least sympathetic, but Kuhn preferred to delegate his wet work. That same day, Joe Cronin sent a telegram to the AL clubs, clarifying that the experimental rule should not be used unless both teams agreed. With that, the experiment was essentially over.

In practice, the three-ball rule injected baseball with the tedium of the final whistle-filled minutes of a close basketball game. He was right to worry that making this work would take a quarter-century no one had. Not only were pitchers completely unprepared to change their style to fit into such a different ruleset, they had no incentive to try. Instead of delving into the strike zone and challenging hitters, the pitchers nibbled away in preparation for their season, issuing 106 walks in just six games. Game durations swelled to anywhere between two hours 40 minutes and nearly four hours. Finley had correctly diagnosed baseball’s problems, but his proposed cure turned out to be poison.

Not every experiment works, but every good idea starts as someone’s “What if…” scheme. Multiple schemes were tested in the American League that spring, but one seemed particularly promising:

What if…pitchers didn’t bat?

It had been tried in the minors without attracting much interest, but Joe Cronin saw a little something in it. He invited American League teams to use a “designated pinch hitter,” replacing the pitcher in their lineups. Most opted in, along with some National League clubs making interleague visits.

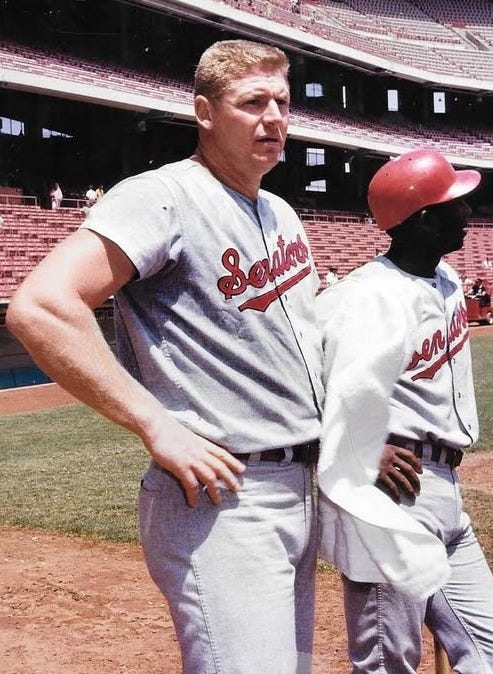

The results weren’t revelatory—designated pinch hitters batted a collective .233, but this was better than a pitcher’s batting line. Managing the Washington Senators, Ted Williams loved the idea, using it in nearly every game. Williams often gave the slot to one of his aging, defensively-challenged stars, players like Curt Flood, rusty from years in baseball exile; and hulking Frank Howard, whose best days in the outfield were long past.

That was something, wasn’t it? The designated hitter role could gracefully add more offense to the game and extend stars’ careers—the people fans came out to see. Wouldn’t it more fun to keep Frank Howard lurking in a lineup, instead of some hapless pitcher?

Charlie Finley knew a good idea when he saw one. Seeing the designated hitter succeed where his own idea had failed, he took up its cause. Thanks in part to Finley’s strident lobbying, the American League adopted the DH for a three-year trial beginning in 1973—a trial that continues to this very day.

One More Thing

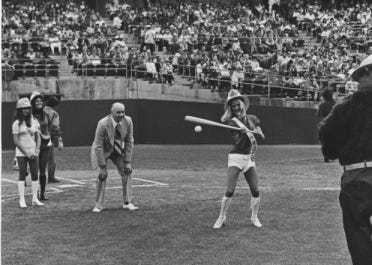

Later that summer, Finley the rule-maker would give way to Finley the promoter, who caught lightning in a bottle with a ballpark gimmick that made him the talk of baseball and inspired a dozen imitators. Researching this story, we were excited to stumble upon an image of the A’s owner participating in his inaugural Hot Pants Day.

Next week, we’ll tell you about the time in 1981 when the Seattle Mariners were literally robbed. It’s a shorter one, so we might add a postscript or two, and give you the chance to give Project 3.18 some feedback!

On March 24: “Sheepish Clothing”

The broad strokes of Finley’s history lesson are correct, but some of the details are a little squishy and oversimplified. For example: the base-on-balls actually appeared in 1863, as a kind of delay-of-game penalty.

Finley was something - quite the iconoclast! Also, I loved Frank Howard - that guy was enormous.

Great piece to read! Who knows what the game would be like today if a three ball walk rule had been accepted? I for one am glad it wasn’t.