A New York Wedding

Spider-Man gets married, Dwight Gooden returns from drug rehab...it's just another day at Shea Stadium.

Disclaimer: This story contains some comic-nerdiness, but we made the difficult editorial decision to confine most of it to the footnotes, so it’s opt-in.

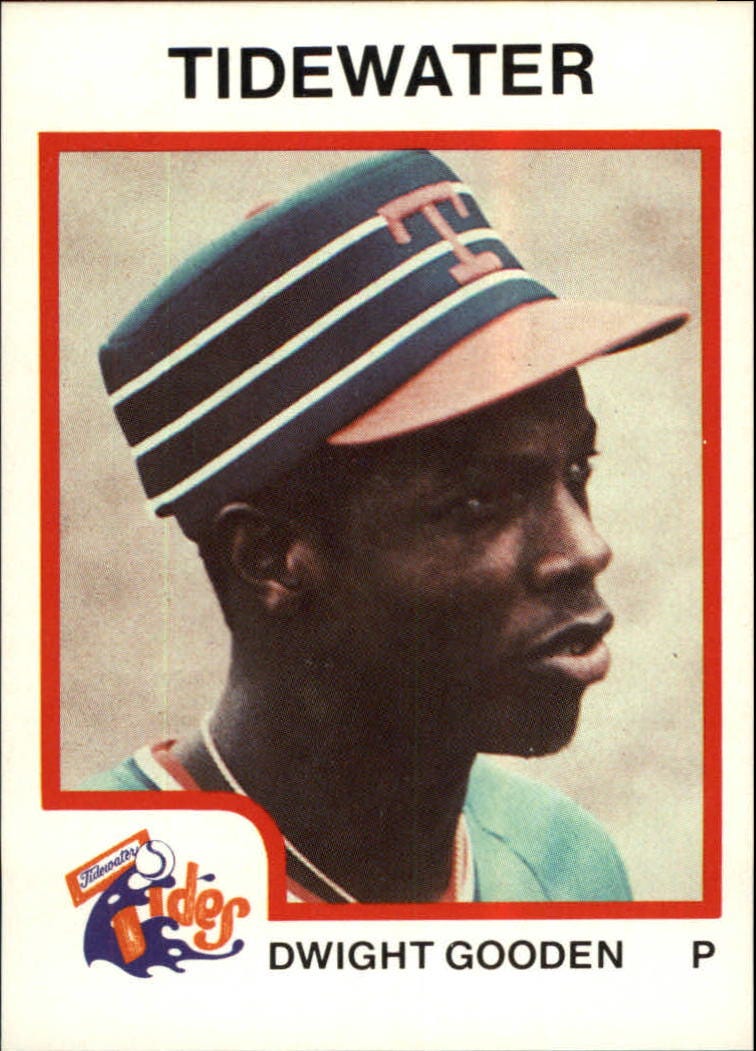

“Superhuman” is an easy bit of hyperbole to throw around, but at the start of his career, Dwight Gooden wore it comfortably. He emerged from a rocket ascent through the minor leagues in 1984—just 19 years old—to immediately become an All-Star, Rookie of the Year, and the instant ace of the New York Mets, a contending club in the nation’s biggest media market. The strikeout numbers were hard to fathom, with 276 punchouts in that first season. “Facing Gooden,” columnist Jim Murray wrote, “a pop fly was a moral victory.”

He came back in 1985 and was even better, giving one of the sport’s all-time great performances. He was indestructible and unhittable—16 complete games, 268 strikeouts, a 1.53 ERA. He won 24 games and the Cy Young award. His youthful greatness was nigh overwhelming. “[Gooden] wouldn’t have a career,” the same writer imagined. “He’d have a parade.”

He remained durable in 1986, but all the other numbers declined. And while most pitchers would gladly take a 17-6 season featuring 200 strikeouts, far fewer would vie for Gooden’s World Series performance, when he allowed 10 runs in 9 innings and threw like he might be hurt. The Mets won anyway, and Gooden was a young star on a championship team—a dangerous combination.

As invulnerable as Dwight Gooden was on the mound, he was highly susceptible to substance abuse, drinking heavily and experimenting with drugs as early as high school, including cocaine. After winning a World Series, he found his hometown of Tampa had become one giant party in his honor, and he would later tell reporters he’d used cocaine regularly that off-season.

Every mistake—including several run-ins with police—became national news, and rumors of a drug problem gained on the Mets’ star. Going into the 1987 season, in an effort to contain the damage, Gooden and the club agreed to a random drug testing stipulation in his contract. The pitcher later said he went along because he’d thought—based on some lucky escapes over the winter—that he could beat the tests.

During 1987 spring training, on March 25, Gooden “got high with two other Mets.” He never named them, but wrote, “they know who they are.” The very next day, the team trainer gave him a drug test, which he failed.

In his autobiography, Gooden explained what happened. “Frank Cashen [the Mets’ general manager] told me that I had two options: I could serve a season-long suspension without pay, or else enter a rehab program. I spent 28 days in rehab.”

He spent those days at the Smithers Center for Alcoholism and Drug Treatment in Manhattan. Meanwhile, the season got underway, and the defending world champions struggled mightily without their star, especially after several other pitchers were quickly lost to injury. After Gooden was released in late April, he embarked on a make-up spring training within the Mets’ minor league system. Having skipped the entire upper half of the minors as a rookie, this would be the first time he’d ever pitched in AA or AAA.

As Gooden pieced his life back together in 1987, a surprising power couple was building theirs. This was an era of celebrity weddings, kicked off by the once-in-a-generation wedding of Charles, Prince of Wales, and Lady Diana Spencer in 1981. More recently, 1986 featured an American Camelot celebration, when Caroline Kennedy, daughter of President John F. Kennedy, married renowned designer Edwin Schlossberg. In a country ever more obsessed with celebrity, weddings became news-cycle heavyweights.

Marvel Comics decided to try and catch the wave. In early 1987, the company announced that Peter Parker (a.k.a. Spider-Man) would finally wed his long-time love interest, Mary Jane Watson. For much of the character’s 25-year publishing history, Peter and MJ had been on and off, relationship setbacks being a key ingredient in the secret sauce of relatability that made the hero so popular. For the wedding, Marvel leaned hard into realism, announcing the news in a press release featuring quotes from “Spider-Man” himself1.

“Hey, we’re not kids anymore,” the webslinger said. “And it’s the 1980s now. Commitment is no longer a dirty word. I’ve made up my mind. I’m taking the plunge!”

The two Queens natives soon found their perfect venue: Shea Stadium.

The idea for the promotion was hatched in early March. “We thought it was a great opportunity for the Mets and Spider-Man,” the Mets’ promotional director said. “They both started at the same time in 1962. It’s meant to be a lot of fun.” Or, according to a more cynical baseball take, “the way the Mets have been playing lately, they could use him in the lineup.”

In May, newspaper advertisements began inviting New Yorkers to a “Marvel-ous Night At Shea Stadium” on June 5, when the “World Champion New York Mets host the wedding of the Amazing Spider-Man.” The IRL ceremony would be followed by the release of Amazing Spider-Man Annual #212 to comic stores on June 9.

To hype the issue and boost sales, Marvel recommended that retailers throw big release parties and decorate with wedding supplies purchased from local sources (at individual storeowners’ expense, of course), triggering a national run on wedding cake and formal stationery. “I’m putting more preparation into this than I did into my own wedding,” one retailer admitted (or bragged?)

Marvel sent actresses portraying Mary Jane to fancy stores like Tiffany’s and Bloomingdales to select and register for wedding gifts. A cake reception was planned for a popular Manhattan nightclub, The Tunnel. And of course there was a Dress.

Mary Jane would wear a $10,000 gown designed by Willi Smith, a successful and in-demand fashion designer who had a hand in more than one celebrity wedding in the 1980s. More than a dozen trendy Seventh Avenue designers submitted ideas, but Smith’s lace-heavy creation (evoking spiderwebs) won out. The choice took on much greater weight when he died of AIDS-related pneumonia in mid-April. Mary Jane’s gown was the last major piece Smith personally completed.

“Willi took the business of having fun very seriously,” the director of publicity for WilliWear—Smith’s design house—said on the eve of the wedding. “He was a very real person. He wasn’t a person who sat on a pedestal. This was right up his alley.”

As Spidey and MJ prepared to marry, Dwight Gooden prepared to pitch, making five starts in the upper levels of the Mets’ minor league system. Gooden would later say he felt he’d lost some intangible “zip” off his fastball as 1986 went on, and that essential ingredient remained missing as he returned to the mound after finishing rehab. Still, what remained—a fastball in the mid-90s and a power curve—made for an excellent pitcher. Despite sometimes being the youngest player on either (minor-league) team, Gooden laid waste to his opponents.

There was increasing pressure to get these preliminaries over with. The Mets had five pitchers on the shelf with injuries and were falling behind their bitter rivals, the St. Louis Cardinals. After Gooden threw six shutout innings in a final AAA start, he was called back to New York.

It was a fraught moment for Gooden, still just 22 years old, returning to Shea as a tarnished wunderkind to face an uncertain public reception. His transition needed to be handled with the utmost care. The Mets did not do that.

“These kind of things, you make a decision and you go with it,” Cashen said. “If you lose the pennant by one game, somebody’ll go back and say, ‘Well, if you’d started him one week earlier…’ But what the hell? You’ve got to do it at the time you’ve got to do it, and go on with life.” Gooden would return on June 5.

Meanwhile, hype was building around the wedding. Who was attending? Would the mayor be there, one breathless preview wondered? What about actress and model Brooke Shields? Or Michael Jackson3?

At least one model, Tara Shannon, would attend, because she’d been hired to portray the bride. Even after Shannon was cast and announced as Mary Jane Watson, she and Marvel persisted in a headache-inducing metafiction, insisting that “Spider-Man would be portraying himself.”

“He’s been pacing the ceiling for weeks,” Shannon was quoted as saying. So, was Spider-Man marrying Mary Jane Watson, or Tara Shannon?

In another Inception-esque kick of illogic, the couple would be wed by their co-creator, Stan Lee.

The overlap of Gooden’s return and Spider-Man’s Big Day was “one of those ironies that life arranges when it tires of subtlety,” David Sarasohn wrote in a syndicated column. The convergence of two flawed stars made him long for the days when comic heroes were nigh-omnipotent and society kept the problems of real heroes—Mickey Mantle’s drinking, JFK’s dalliances—tightly under wraps:

Our insistence on our heroes being human ends up diminishing not only them but us. It has taken away reverence and left us with only hype.

While Sarasohn and many other writers seemed ready to give the pitcher another chance, one loud, wrathful voice hijacked the discourse.

After spending decades as one of the foremost American baseball writers, Dick Young was now in semi-retirement, writing for the New York Post as targets presented. Years had not softened the 69-year-old bomb-thrower, and in Gooden’s fall from grace he saw plenty to abhor.

“What has Dwight Gooden done exactly since the last game he won for the Mets?” Young wrote.

He has sniffed coke. He has been stopped by the Tampa police for playing chicken on the Dale Mabry Highway. He has brawled with police. He was drunk in the hospital. He has gone through a drug rehab institute in a record 27 days. All this, I suppose, adds up to his being a typical American hero, and so we will stand and pay homage to Dwight Gooden.

If he had his way, Young wrote, Mets fans would instead “stand up and boo,” letting the pitcher know “how society feels about the wrong he has done, about the damage he has committed to the millions of kids who worshipped him.”

Emerging from the Mets’ dugout on June 5, first baseman Keith Hernandez confronted a horde of reporters and extra police, and the distant sight of enterprising fans standing three and four deep to watch the game from the “El” platform beyond right field.

“What is this, Game Seven?”

“It was a happening,” columnist Jim Murray wrote of the game, (number 51 on the season). “It had elements of a Broadway opening, a bar mitzvah and a society debut all rolled into one. You had to be there if you were anyone.”

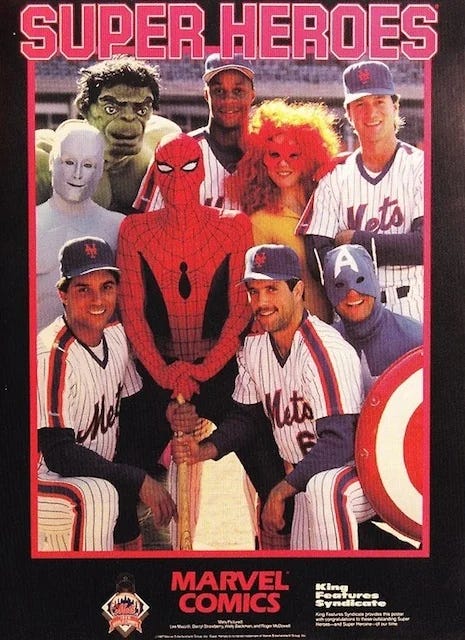

51,000 lucky anyones received an advance copy of the comic-version of the wedding and a promotional poster featuring costumed Marvel characters shoulder to shoulder with Wally Backman, Darryl Strawberry, Roger McDowell, and Lee Mazzilli.

The swag was nice, but the stands were full for Dwight Gooden.

He couldn’t sleep the night before. He wondered how his stuff would be, what reception he’d get. He got to the park and tried to keep a low profile, playing cards with some of his teammates as the hours crept by. Cashen had forbade reporters from speaking to Gooden before his start and the Mets’ manager, Davey Johnson closed the clubhouse. The visiting Pirates quickly closed theirs, too. ”I’m not going to let Davey Johnson drive all those writers over here,” manager Jim Leyland said.

Gooden’s parents and infant son were at the park to support him. Dr. Allan Lans, an associate director of Smithers, was on hand to point out the obvious: “Who needs this?” he asked. “It’s horrible. In my way, it would have been as routine an evening as possible. But it’s one of those crazy things, where the schedule was already made.”

Cashen offered a hollow defense. “How did I know that Spider-Man was going to get married on the same day?” Apparently he did not read the newspapers.

Before the ceremony, the bride and groom gave a locker room interview. Despite the questions and answers being scripted, it was all remarkably awkward. Asked about kids, MJ said, “As long as they are healthy, have two arms and eight legs, I’ll be happy.”

Why would you be happy about that?4

Stan Lee and Marvel’s other writers had spent the past 20 years making Peter Parker miserable by introducing rival love interests for Mary Jane, and the day’s festivities were filled with specious references to her dating history.

Why Shea, she was asked. “Because I have so many ex-boyfriends—I had to have a place large enough to hold them all.”

Wow.

Spider-Man had a better answer. “I’m a New York hero—just like the Mets,” he said, shoving a too-tight Mets cap on over his spandex.

A 27-piece band played as the couple rode onto the field atop separate Cadillac limousines. Wearing Willi Smith’s gown, MJ was “resplendent in satin, lace, and ruffle high-neck and form-fitting gown with a diaphanous bodice and flounce at the knee.”

Spider-Man was dressed in his usual red-and-blue, with an infusion of white-tie, coat-and-tails elements (also designed by Smith), and if you ask us, it looks pretty good.

Stan Lee, Marvel’s founder, publisher, and media figurehead, waited at home plate to perform the ceremony, along with a haphazard wedding party of Captain America (best man, naturally), the Incredible Hulk, a random member of the X-Men, Firestar (had to look that one up). The bride’s side had no one, but Spider-Man’s arch-nemesis, the Green Goblin5 got invited. Lee got right to work.

“Do you, Spider-Man, being of sound mind and super-body, take Mary Jane to be your lawfully wedded bride, forsaking all other superheroines? Do you promise to never leave footprints on the walls or ceilings, or cobwebs in the corners? Do you agree to pinch hit for the Mets if they ask you?”

He did. It was Mary Jane’s turn, and the 1980s cringe peaked:

“Mary Jane, do you, being of sound mind and spectacular body, agree to forsake other masked Marvelites, to never ever swat a spider, and to hug, comfort, and kiss away any bruises incurred after a long day of bashing bad guys—and stay out of the Mets’ locker room?”

Stay out of the locker room? Really?

Dubious vows in effect, Spider-Man dipped and kissed his bride.

During the ceremony, a pitcher quietly stood up in the Mets’ bullpen and began to throw. Hardly anybody noticed. Spider-Man, a friend to all in the neighborhood, gave Dwight Gooden a few extra moments to get himself together before the Shea spotlight found him.

The newlyweds limo-ed around the field again and disappeared, as did Lee, who did not attend the reception. The band played “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “Meet the Mets” blared from loudspeakers as the home team took the field.

“I was prepared for it to go the other way,” Gooden said. With good reason. Newspapers were filled with New Yorkers who felt he’d gotten off too easy—one local deli had even withdrawn their signature Dwight Gooden sandwich—and Dick Young had tried to hammer all those hard feelings into a point. But as he took the mound, Gooden heard only cheers. The sellout crowd gave him a standing ovation, and he returned the greeting with a tip of his cap and a strikeout of the Pirates’ lead-off hitter, the dangerous Barry Bonds.

“I was trying to relax, but I had butterflies all day,” Gooden said. “Getting that first out was the biggest part, and the crowd was tremendous.”

“Nothing felt comfortable in the beginning,” he said. He stuck with his breaking ball, figuring batters would be looking for the fastball. He was tentative and mistrustful, regularly shaking off his catcher, Gary Carter.

Jim Murray said Gooden “worked a lot of long counts.” He went six and two-thirds innings, allowing four hits, four walks, and giving up one run. He struck out a modest five batters. In this pre-Statcast era, the attentive Murray counted 11 pure fastballs, not many for strikes. “The Pirates,” he noted, “hit a lot of line drives.”

His teammates helped where they could. Left fielder Mookie Wilson and center fielder Lenny Dykstra crashed together in left center, chasing the same two-out fly ball. Both men were left bloodied, and three Pirates circled the bases until Wilson roused himself and opened his glove to reveal the ball within.

Gooden left in the sixth to another standing ovation. New York went on to win the game, 5-1.

“It was good to get this game over with,” Gooden said afterward. “Now I can go on and feel part of the team again.” It was the first time he’d spoken to reporters in two months. The Mets had prohibited anything but baseball questions. In return, Dick Young sat in the front row and asked Gooden if he agreed with the Mets’ journalistic censorship.

All Mets were New York celebrities in 1987, but even they could see the larger burden Gooden carried. “We’re expecting a lot from Dwight,” second baseman Wally Backman said. “Maybe we’re expecting too much. Sometimes it seems like we’re waiting for the Messiah.”

The Mets were desperate for some good news on the pitching front, and now they finally had some. As one sign-maker in the crowd put it:

“The Doctor is IN.”

But the Doc’s return only covered one of the Mets’ many vacancies. “All I want to know is if Spider-Man can throw a good fastball,” Davey Johnson said. “The way we’ve been going, we can use another arm.”

Or four.

For those who couldn’t attend, Marvel released “Spider-Man’s Wedding Album,” a film package of the TV press coverage and lots of clips of the ceremony and prenuptial interviews. We have no idea how it would have been distributed at the time, but these days it’s on YouTube. Again, this is opt-in.

We also found canon proof that both Spider-Man and Captain America are Mets fans—check that out over on Project 3.18-stagram!

We hope you’ve enjoyed a month in the 1980s. We’re going to work our way backward from here, lest we get too close to the 1990s and melt.

Next week we’ll be in 1963, bringing you a story of endurance, obstinance, and a kind of greatness we’ll never see again.

On February 10: “You First”

For reasons that defy explanation, Spider-Man’s real name was never used, even during the vows. It was never “Peter Parker” getting married, it was always “Spider-Man.” If this was a measure to protect his secret identity, surely it was mooted by the very public ceremony and the use of Mary Jane’s full name. Any super-villain with a phone book could work backward from there.

Featuring two collectible cover variants—the industry was warming-up for the 1990s.

No, no, and probably not.

In the comic, Mary Jane feared that Parker’s irradiated spider-genes would end up harming their future children. But here was real-world MJ, openly rooting for this to happen!

Even casual Marvelites will recall that the Green Goblin murdered Spider-Man’s first love interest, Gwen Stacy (ASM Ish #121–STAN), so what on earth was he doing in this wedding party? $10,000 for a wedding dress but they just grabbed the first five costumes they found on the rack.

Boy, that promotion is quite “Veeck-like.”

With great power comes great responsibility so I thought I should let you know that the kids refer to Instagram as "IG" these days, in case you want to reach that audience :)